По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

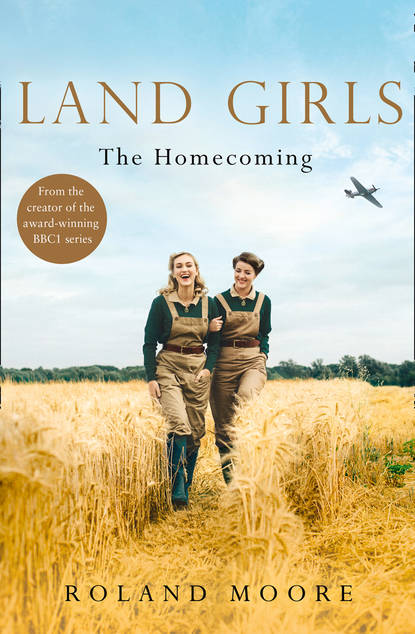

Land Girls: The Homecoming: A moving and heartwarming wartime saga

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The guard shook his head and walked down the platform.

“Someone’s got to sweep it up,” he muttered. “That’ll be me, won’t it?”

Connie didn’t have the energy to argue. Her back was sore and her feet were throbbing from digging all day at Brinford Farm, where she and some of her fellow Land Girls had been seconded. She’d been at it since six in the morning and now it felt that even her blisters had blisters. Connie just wanted to get back to Helmstead: the picturesque village on the edge of the Cotswolds, where she was usually billeted as a Land Girl. The twin delights of a hot bath and her husband would be waiting. Helmstead had been home for the last year – a place where she was finally part of a family, of sorts. A place where she’d married Henry Jameson one month ago.

Connie and Henry were an odd match in a lot of ways. She was a worldly young woman from Stepney in the East End; he was a naive vicar from the countryside, a man who had never even been to London. Some likened it to a wild cat marrying a tortoise. She’d try to shrug off the disapproving looks from the older members of the village; those who thought she wasn’t good enough to be a vicar’s wife. But the sour expressions and the comments hurt Connie deeper than she’d ever let on. Sometimes she’d close the bathroom door and confused thoughts would race through her head. What if they were right? Why couldn’t they just accept her? She was trying her best. All she wanted to do was fit in. There was a nagging feeling that she didn’t belong here and that one day she’d have to accept that fact and move on. It was difficult to put down real roots when you felt they were going to be ripped up soon.

But when she could shut those thoughts out of her mind and focus on herself and Henry, she liked the stability he brought into her life. She thought that perhaps he liked the spark that she brought into his. Perhaps her lust for life inspired Henry. Certainly his sensible ways tempered her from getting into too much trouble. Certainly, in a lot of ways, they would infuriate each other and Connie was mindful never to push him too far. If he didn’t want to do something spontaneously, Connie would back down. She knew she wasn’t an easy fit for the world of village cricket and afternoon teas at the vicarage and she didn’t want to risk losing that. So she’d keep her thoughts to herself while secretly thanking her lucky stars that such a warm, decent man had taken her to his heart. It was too good to be true and she had to pinch herself for the chocolate-box turn that her life seemed to have taken.

Since meeting Henry, Connie rarely thought of those times before she joined the Women’s Land Army; shutting out those dark bedsit days and endless nights. It had been a different time. A life that she hoped she’d never have to go back to.

Connie’s thoughts were broken as a rough, wooden broom ran over her boots.

“Oi, do you mind?” Connie spluttered.

The old guard was sweeping the platform with an irritated staccato motion, sending clods over the side onto the track, where they would be someone else’s problem.

“Disgraceful,” the guard replied, without dignifying Connie with eye contact. “Brinford won silver in Best Rural Station last year. I don’t need this clutter on me concourse.”

“There is a war on,” Connie muttered, not giving a damn for his concourse. What was a concourse anyway? The guard continued along the platform, the wide broom head scything a path through the waiting passengers.

Suddenly Connie felt a tap on her back. She turned around, her mouth ready to unleash some angry words on any do-gooder. So what if her boots were muddy? She probably had dirt in her hair and was enveloped in the unmistakable perfume of cow dung too. But it was a friendly face that greeted her. Joyce Fisher was smiling at her. Mid-twenties, a little older than Connie, Joyce was stoic and sensible, with a sunny surface. She was a woman committed to patriotism and doing her bit to win the war. After all, that was all Joyce had to cling onto, wasn’t it? She’d lost so much and all the time the war was raging it stopped her dwelling on the thoughts of loss in her own head. The family gone forever in Coventry. If the war ever ended, then Connie suspected that Joyce would find the silence hard to deal with.

“I thought I was going to miss the train,” Joyce said, her soft eyes and sensible permed hair a welcome and reassuring sight.

“There’s no sign of it yet,” Connie replied. “Still, doubt it’ll be late.”

Joyce sighed in relief, unflappable as always. She handed Connie a small greaseproof-paper packet. “Cheese and an apple,” Joyce said, by way of explanation. She’d waited behind at Brinford Farm as the farmer’s wife had offered some food for their journey back to Helmstead. Joyce was worried that, despite the woman’s kindness, she would take so long to wrap it all up that Joyce would miss the train. Not to mention the next one. “But I didn’t want to be rude and just walk off.”

Connie thanked Joyce and they opened their wrappers. Connie bit into her apple, wrapping the cheese back up for later. She knew Henry might like a bit of that.

The guard stopped his sweeping and eyed them suspiciously. “Hope you’re not making any more mess,” he muttered, moving with surprising speed back towards them. How could he have heard them unwrap a package at that distance?

“I’ve a good mind to give him what for,” Connie said under her breath. She’d always fought her own battles and would never back down from a scrap. But this time Joyce touched her arm, holding her back. Joyce believed it was better to pick your battles, not engage in every skirmish at once.

“I leave you for ten minutes and all sorts happen. What’s going on here?” Joyce asked.

Connie shook her head. It was nothing.

“That’s what you said when you smashed the pub window.” Joyce smiled.

Connie smiled at that memory too, a little embarrassed and amazed that she’d had the brass neck to do that. But the landlord had diddled them out of change one too many times. And he was a lecherous old sod, who made them all feel uncomfortable with his roving eyes. Henry had been annoyed about that, drifting into a sullen sulk for several days until Connie blurted out an apology. He’d given her a lecture about turning the other cheek. Connie had found herself drifting off as the words washed over her; annoyed that Henry was patronising her as if she was still a little girl at the children’s home.

In the early evening sun, the two weary friends stretched their aching backs and Connie ate her apple. Behind them, a poster warned housewives not to take the trains after four o’clock so that factory workers could use them. Another showed two women chatting, not realising that a sinister man in a hat and coat was ear-wigging. Careless talk costs lives. Some more RAF pilots from Brinford Air Base decamped on the platform, their bodies laden with kit bags and great-coats. Connie scanned all the faces on the platform. She and Joyce were the only two Land Girls heading back. But there was an assortment of other travellers – service men, factory workers, a policeman and a middle-aged woman, who was clutching the hand of a nine-year-old girl. The little girl, her blonde hair in ringlets in a style that had been popular ten years ago, had been crying. Connie noticed the snaking lines of old tears on her chubby face and the way she was sniffing as she tried to control the flow. Before Connie could look any more, a portly man obscured her view – his shirt stretched tight over his large belly like the tarred cloth around Finch’s haystack. The man’s eyes darted to the distance in search of the train. He wore a trilby hat and a camera dangled around his neck, resting on the cushion of his stomach.

Suddenly the guard blew his whistle and everyone perked up as the plume of smoke from the steam train was glimpsed from behind a hill. Slowly the train chugged into view and Connie forgot the other passengers on the platform. Now it was all about getting a seat in one of the carriages. She needed to sit down. And from the weary look on Joyce’s face, she did too. The two friends walked to the edge of the platform, trying to predict the position where the carriage doors would be. This was a routine that they had perfected since their secondment to Brinford. Each evening they would wait for the train. Each evening they would try their best to secure a seat in one of the crowded carriages. The train came to a halt, the smell of soot thick in the air. The passengers already on-board flowed out of the carriage doors like water from a colander. And, with the train vacated there was the relatively good-natured but nonetheless urgent rush of the new passengers to find a seat. Some soldiers held back, allowing Connie and Joyce to get on first. Connie smiled charmingly back – thank you, kind sirs – and then suddenly darted, with little hint of any ladylike grace, along the carriage corridor to find an empty compartment.

They ducked under an RAF flyer’s arms as he hoisted his kit bag up into the baggage rack and found themselves in an empty six-seat compartment. Mission accomplished! Connie and Joyce sat nearest the windows – until Joyce quickly changed her mind and sat next to Connie.

“Forgot, I don’t like going backwards.”

As the carriages filled up and the guard’s whistle became more impatient, Joyce asked Connie whether Henry would be at the vicarage when she got home. Connie didn’t know. Often Henry would cycle around the village in the evenings, administering succour and support to his parishioners.

“I told him, he wants to kick those needy old biddies into touch, he’s a married man now,” Connie said, partly to make Joyce laugh and partly to shock the middle-aged businessman who had entered their compartment. The businessman sat down and defensively rustled his newspaper open, a makeshift shield of the Times crossword to block out such coarseness for the duration of the journey.

The compartment filled up. The young girl who had been crying and her stern-looking mother entered. And then a fresh-faced young soldier arrived to make up the six. He sat down and studiously attempted to roll a cigarette for the first ten minutes of the journey. He obviously hadn’t been smoking long and was all fingers and thumbs, with more tobacco ending up in his lap than in the cigarette paper. Connie was itching to snatch it from him and do it herself, but figured that wouldn’t be the sort of thing a lady would do.

Joyce and Connie settled down for the journey as the train wheezed its way out of Brinford, the station guard diminishing to the size of a speck on the platform. He could be alone with his concourse now.

“Why are you still calling yourself Carter?” Joyce asked, breaking Connie’s idle thoughts. “Heard you introduce yourself twice today.”

“Had that name all me life. Not got used to being a Jameson yet, I suppose.” Connie shrugged. “Connie Carter’s got a ring to it.”

“She’s got a ring on her finger,” Joyce retorted.

Why hadn’t Connie been using Henry’s name? It was an odd thing for her to do. Married women happily took their husbands’ surnames. Secretly she knew that her explanation to Joyce was a lie. She didn’t use the name of Jameson because she didn’t believe it would last. Nothing ever did in her life. Part of her thought that her happy marriage would be a blip. Best not to get too comfortable with the luxury of Henry’s surname. Another part of her hated herself for hedging her bets and not fully committing. She should dive in rather than just dangling her feet in the pool. But that’s what came when you were buffeted from a lifetime of disappointment and rejection.

Connie shut out the thoughts and concentrated on the stern-looking woman and her tearful daughter. Connie offered a consoling smile to the girl, but the girl didn’t acknowledge it. Was she too upset to notice? Or was it fear making her reluctant to smile back?

“My John’s supposed to be on this train,” Joyce said, interrupting Connie’s thoughts. “But I didn’t see him on the platform.”

“Difficult to see anyone in that scrum, wasn’t it?” Connie offered.

John Fisher – an RAF flier – had been to the airbase in Brinford today and Joyce had been hoping to see her husband before they got back to Helmstead. He was Joyce’s rock – her childhood sweetheart and the only part of her family that she hadn’t lost in the brutal bombing of Coventry at the start of the war. It had been a lucky accident, which had meant they were in Birmingham on the night the bombs dropped. A sliver of serendipity that further cemented their relationship and their belief in their shared destiny together.

“Do you want to go down the carriages and find him?” Connie asked. “I’ll keep your seat.”

Joyce looked at the corridor outside their compartment. It was crammed with soldiers, pilots and factory workers. It would be nearly impossible to move down the train. Joyce decided to stay where she was. “I’m sure I won’t forget what he looks like if I don’t see him until Helmstead.”

The young soldier dutifully finished his roll-up with an audible gasp of satisfaction. But the victory was short-lived as he raised it to his lips and lit it; it promptly unrolled, dropping tobacco onto his trousers. He cursed and hastily patted his crotch to put out the burning embers before they scorched his uniform. Connie couldn’t resist letting out a small laugh. The boy looked back and smiled. He scooped up the tobacco and started to try again.

“Want me to do it?” she offered. Sod it if it wasn’t the sort of thing a lady did.

“Can you roll them?” the soldier said in surprise, a glimmer of hope in his eyes.

“No. But I can’t be worse than you, can I?”

Joyce nudged Connie to stop messing with the poor lad. “What? I’m just being friendly,” Connie said, under her breath. The middle-aged woman with the tear-streaked daughter shot her a disapproving look.

The soldier sucked in his cheeks and doggedly resumed his rolling.

The businessman already had a pipe in his mouth – unlit at the moment and being sucked on like a baby’s dummy as he contemplated the crossword.

The train snaked across the countryside. Fields of cows and fields of corn moved past the windows like frames at the flicks. The evening sun glinted low through the carriage windows, dappling the occupants with patchworks of light.

Connie entertained fragmented thoughts: Henry waiting with a cup of tea; Joyce joking in the fields with her; the snotty guard at Brinford station. The images washed over her in a hazy, comforting blur as the motion of the train and the evening sunlight flickered over her face. Sleep was a moment away.

The fields trundled by in a blur.