По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

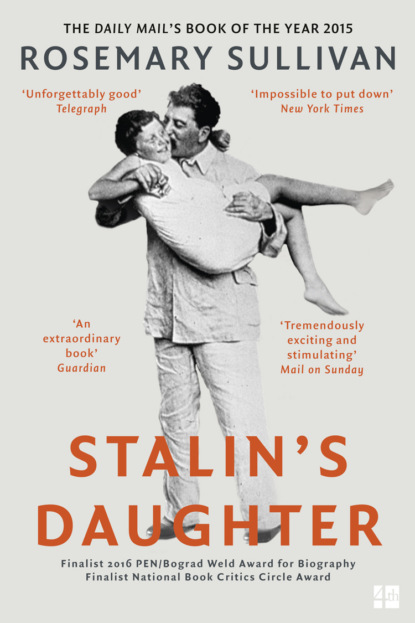

Stalin’s Daughter: The Extraordinary and Tumultuous Life of Svetlana Alliluyeva

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Danny Wall, the marine guard on desk duty, opened the door. He looked down at the small woman standing before him. She was middle-aged, neatly dressed, nondescript. He was about to tell her the embassy was closed when she handed him her passport. He blanched. He locked the door behind her and led her to a small adjacent room. He then phoned Robert Rayle, the second secretary of the embassy, who was in charge of walk-ins—defectors. Rayle had been out, but when he returned the call minutes later, Wall gave him the secret code indicating the embassy had a Soviet defector, the last thing Rayle was expecting on a quiet Monday evening in the Indian capital.

When Rayle arrived at the embassy at 7:25, he was pointed to a room where a woman sat talking with Consul George Huey. She turned to Rayle as he entered, and almost the first thing she said to him was: “Well, you probably won’t believe this, but I’m Stalin’s daughter.”

Rayle looked at the demure, attractive woman with copper hair and pale blue eyes who stared steadily back at him. She did not fit his image of Stalin’s daughter, though what that image was, he could not have said. She handed him her Soviet passport. At a quick glance, he saw the name: Citizeness Svetlana Iosifovna Alliluyeva. Iosifovna was the correct patronymic, meaning “daughter of Joseph.” He went through the possibilities. She could be a Soviet plant; she could be a counteragent; she could be crazy. George Huey asked, nonplussed, “So you say your father was Stalin? The Stalin?”

As the officer in charge of walk-ins from the Soviet bloc, Rayle was responsible for confirming her authenticity. After a brief interview, he excused himself and went to the embassy communications center, where he cabled headquarters in Washington, demanding all files on Svetlana Iosifovna Alliluyeva. The answer came back one hour later: “No traces.” Headquarters knew nothing at all about her—there were no CIA files, no FBI files, no State Department files. The US government didn’t even know Stalin had a daughter.

While he waited for a response from Washington, Rayle interrogated Svetlana. How did she come to be in India? She claimed that she had left the USSR on December 19 on a ceremonial mission. The Soviet government had given her special permission to travel to India to scatter the ashes of her “husband,” Brajesh Singh, on the Ganges in his village—Kalakankar, Uttar Pradesh—as Hindu tradition dictated. She added bitterly that because Singh was a foreigner, Aleksei Kosygin, chairman of the Council of Ministers, had personally refused her request to marry him, but after Singh’s death, she was permitted to carry his ashes to India. In the three months she’d spent here, she’d fallen in love with the country and asked to be allowed to stay. Her request was denied. “The Kremlin considers me state property,” she said with disgust. “I am Stalin’s daughter!” She told Rayle that, under Soviet pressure, the Indian government had refused to extend her visa. She was fed up with being treated like a “national relic.” She would not go back to the USSR. She looked firmly at Rayle and said that she had come to the American Embassy to ask the US government for political asylum.

So far, Rayle could conclude only that this utterly calm woman believed what she was saying. He immediately understood the political implications if her story was true. If she really was Stalin’s daughter, she was Soviet royalty. Her defection would be a deep psychological blow to the Soviet government, and it would make every effort to get her back. The American Embassy would find itself in the midst of a political maelstrom.

Rayle remained suspicious. He asked her why her name wasn’t Stalina or Djugashvili, her father’s surname. She explained that in 1957 she had changed her name from Stalina to Alliluyeva, the maiden name of her mother, Nadezhda, as was the right of every Soviet citizen.

He then asked where she had been staying. “At the Soviet Embassy guesthouse,” she replied, only several hundred yards away. How had she managed to slip away from the Soviet Embassy without being noticed? he asked. “They are having a huge reception for a visiting Soviet military delegation and the rest of them are celebrating International Women’s Day,” she replied. He then asked her how much time she had before her absence at the guesthouse would be noticed. She might have about four hours, she explained, since everyone would be drunk. Even now she was expected at the home of T. N. Kaul, the former Indian ambassador to the USSR. She said in sudden panic: “I really have to call his daughter, Preeti, to let her know I’m not coming.”

For Rayle this was a small test. He replied, “OK, let me dial the number for you.” He searched for the number, dialed, and handed her the phone. He listened as she explained to T. N. Kaul and to his daughter that she had a headache and wasn’t going to make it for dinner. She said her affectionate good-byes to both.

Then she passed Rayle a battered sheaf of paper. It was a Russian manuscript titled Twenty Letters to a Friend and bearing her name as author. She explained that it was a personal memoir about growing up inside the Kremlin. Ambassador Kaul, whom she and Brajesh Singh had befriended in Moscow, had carried the manuscript safely out of the USSR a year ago January. As soon as she’d arrived in New Delhi, he returned it to her. This was astonishing: Stalin’s daughter had written a book. What might it reveal about her father? Rayle asked if he could make a copy of it, and she assented.

Following his advice as to the wording, she then wrote out a formal request for political asylum in the United States and signed the document. When Rayle warned her that, at this point, he could not definitely promise her asylum, Svetlana demonstrated her political shrewdness. She replied that “if the United States could not or would not help her, she did not believe that any other country represented in India would be willing to do so.” She was determined not to return to the USSR, and her only alternative would be to tell her story “fully and frankly” to the press in the hope that she could rally public support in India and the United States.

The refusal to protect Stalin’s daughter would not play well back home. Svetlana understood how political manipulation worked. She’d had a lifetime of lessons.

Rayle led Svetlana to a room on the second floor, handed her a cup of tea and some aspirins for the splitting headache she’d developed, and suggested she write a declaration—a brief biography and an explanation of why she was defecting. At this point, he excused himself again, saying he had to consult his superiors.

The US ambassador, Chester Bowles, was ill in bed that night, so Rayle walked the ten minutes to his home in the company of the CIA station chief. Ambassador Bowles would later admit that he had not wanted to meet Svetlana personally on the chance that she was simply a nutcase. With Bowles’s special assistant Richard Celeste in attendance, the men discussed the crisis. Rayle and his superiors realized there was not going to be enough time to determine Svetlana’s bona fides in New Delhi before the Soviets discovered she was missing. Bowles believed that the Soviet Union had so much leverage on the government of India, which it was supplying with military equipment, that if it found out Svetlana was at the US Embassy, Indian forces would demand her expulsion. The embassy would have to get her out of India.

At 9:40 p.m., a second flash cable was sent to headquarters in Washington with a more detailed report,

stating that Svetlana had four hours before the Soviet Embassy noted her absence. The message concluded, “Unless advised to the contrary we will try to get Svetlana on Qantas Flight 751 to Rome leaving Delhi at 1945Zulu (1:15 AM local time).” Eleven minutes later, Washington acknowledged receipt of the cable.

The men discussed their options. They could refuse Svetlana help and tell her to return to her embassy, where it was unlikely her absence had been noticed. But she’d made it clear she would go to the international press with the story. They could keep her in Roosevelt House or in the chancery, inform the Indians that she’d asked for asylum in the United States, and await a court decision. The problem with this option was that the Indian government might take Svetlana back by force. The embassy could try to spirit her out of India covertly. None of these were good options.

The deciding factor was that Svetlana had her Soviet passport in her possession. This was unprecedented. The passports of Soviet citizens traveling abroad were always confiscated and returned to them only as they boarded their flights home. That afternoon the Soviet ambassador to India, I. A. Benediktov, had held a farewell luncheon for Svetlana. It was a grim affair. He was furious with her because she had delayed her departure from India long past the one month authorized by her Russian visa, and Moscow was now demanding her return. She was compromising his career. She would be getting on that flight back to Moscow on March 8.

“Well, if I must leave,” she’d said, “where’s my passport?” Benediktov had snarled to his aide: “Give it to her.”

Here Svetlana showed she truly was Stalin’s daughter. When she demanded something, she was not to be refused. Benediktov had made a huge mistake that he would pay for later. For the Soviets, Svetlana was the most significant defector ever to leave the USSR.

Sitting in his sickbed, Chester Bowles made a decision. With her Indian papers in order and her Russian passport, Svetlana could openly and legally leave India. He ordered a US B-2 tourist visa stamped in her passport. It would have to be renewed after six months. He asked Bob Rayle if he would take her out of India. Rayle agreed. The men returned to the embassy.

It was 11:15 p.m. As they prepared to leave for the airport, Rayle turned to Svetlana. “Do you fully understand what you are doing? You are burning all your bridges.” He asked her to think this over carefully. She replied that she had already had a lot of time to think. He handed her $1,500 from the embassy’s discretionary funds to facilitate her arrival in the United States.

She was led down a long corridor to an elevator that descended to the embassy garage. Clutching her small suitcase, which contained her manuscript and a few items of clothing, she climbed into a car. A young marine sergeant and the embassy Soviet affairs specialist, Roger Kirk, recently back from Moscow, climbed in beside her. They smiled. It was electrifying to be sitting next to Stalin’s daughter. She wondered, “Why did Americans smile so often? Was it out of politeness or because of a gay disposition?” Whatever it was, she, who had never been “spoiled with smiles,” found it pleasant!

Rayle phoned his wife, Ramona, to ask her to pack his bags for a trip of several days and to meet him at Palam airport in one hour. He did not tell her where he was going. He then went to the Qantas Airlines office and bought two first-class open tickets to the United States, with a stopover in Rome. He soon joined the other Americans at the airport—by now there were at least ten embassy staff members milling about in the relatively deserted terminal, but only two sat with Svetlana.

Svetlana easily passed through Indian customs and immigration and, in five minutes, with a valid Indian exit visa and her US visitor’s visa, joined Rayle in the international departure lounge. When Rayle asked her if she was nervous, she replied, “Not at all,” and grinned. Her reaction was in character. Svetlana was at heart a gambler. Throughout her life she would make a monumental decision entirely on impulse, and then ride the consequences with an almost giddy abandon. She always said her favorite story by Dostoyevsky was The Gambler.

Though outwardly cool, Rayle himself was deeply anxious. He was convinced that, as soon as they discovered her missing, the Soviets would definitely insist that she be handed over. If she was discovered at the airport, the Indian police would arrest her, and there would be nothing he could do. He felt the consequences for her would be grave.

Execution would have been the old Stalinist style, but her father had been dead fourteen years. Still, the current Soviet government took a hard line on defectors, and imprisonment was always a possibility. When the classical dancer Rudolf Nureyev defected in 1961, he was sentenced in absentia to seven years’ hard labor. In Rayle’s mind must also have been the recent trials of the writers Andrei Sinyavsky and Yuli Daniel. In 1966 they’d been sentenced to labor camps for their “anti-Soviet” writings, and they were still languishing there. The Kremlin would not risk a public trial of Svetlana, but she might disappear into the dark reaches of some psychiatric institution. Svetlana, too, must have had this in mind. Sinyavsky was an intimate friend. At least she knew that, were she apprehended, she would never be allowed out of the Soviet Union again.

The Qantas flight to Rome landed punctually, but Rayle’s relief soon turned to dread as he heard the announcement that the flight would be delayed. The plane had developed mechanical difficulties. The two sat in the departure lounge waiting as minutes turned to hours. Rayle looked at Svetlana. She, too, had begun to be agitated. To cope with the mounting tension, Rayle got up periodically to check the arrivals desks. He knew that the regular Aeroflot flight from Moscow arrived at 5:00 a.m. and a large delegation from the Soviet Embassy always came to greet the diplomatic couriers and the various dignitaries arriving or departing. Members of the Aeroflot staff were already beginning to open their booth. Finally, the departure for Rome was announced. At 2:45 a.m. the Qantas flight for Rome was airborne at last.

As they were in midair, a cable about the defector arrived at the American Embassy in New Delhi. In Washington Donald Jameson, who served as CIA liaison officer to the State Department, had informed Deputy Undersecretary of State Foy Kohler of the situation. Kohler’s reaction was stunning—he exploded: “Tell them to throw that woman out of the embassy. Don’t give her any help at all.”

Kohler had recently served as American ambassador to the USSR and believed that he had personally initiated a thaw in relations with the Soviets. He didn’t want the defection of Stalin’s daughter, especially coinciding with the fiftieth anniversary of the Russian Revolution, muddying the waters. When the embassy staff read the flash cable rejecting Svetlana’s appeal for asylum, they replied, “You’re too late. They’ve gone. They’re on their way to Rome.”

The staff failed to check the status of the Qantas flight. Had they discovered that Svetlana and Rayle were sitting for almost two hours in the airport lounge and could have been recalled, Svetlana would have been driven back to the embassy and “kicked out.” The whole course of her life would have gone very differently. But Svetlana’s life always seemed to dangle on a thread, and chance or fate sent her one way rather than another. She would come to call herself a gypsy. Stalin’s daughter, always living in the shadow of her father’s name, would never find a safe place to land.

PART ONE (#ulink_9cc4c160-23b5-5902-8686-39402c7fd67e)

Chapter 1 (#ulink_ba03478c-ef0f-5980-b4ee-27765e94a3d5)

That Place of Sunshine (#ulink_ba03478c-ef0f-5980-b4ee-27765e94a3d5)

Family group, c. 1930. Standing, from left: Mariko and Maria Svanidze, Stalin’s sisters-in-law from his first marriage. Seated in center, from left: Alexandra Andreevna Bychkova (Svetlana’s nanny), Nathalie Konstantinova (governess), and Svetlana’s maternal aunt Anna Redens. Front row, from left: Svetlana and her brother, Vasili, with Nikolai Bukharin’s daughter sitting on his knee. Standing on right: Sergei Alliluyev, Svetlana’s maternal grandfather.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)

Over her lifetime, Svetlana often would take out the photographs from her early childhood and muse over them, experiencing that lovely, brutal nostalgia of photos trapping time. Her mother had always been the one with the camera taking the pictures. Everyone at the family gatherings was so young and alive, so simple and ebullient, wearing a picnic face. The first six and a half years of her life, until her mother’s death in 1932, were, in Svetlana’s mind, the years of sun. She would speak of “that place of sunshine I call my childhood.”

Who can live without personal retrospect? We will always glance back to our childhood, for we are shaped deep in our core by the impress of our parents, and we will always wonder how that molding determined us. Svetlana willfully believed in her happy childhood, even as she gradually understood that it was secured by untold bloodshed. What was it about this strange childhood that she would always turn to it for solace?

Svetlana grew up in the Kremlin, the citadel of the tsars, a walled fortress on the edge of the Moskva River, almost a small autonomous village but with imposing towers, cathedrals, and palaces centered on Cathedral Square with massive gates opening onto Red Square and the city beyond. One might think this royal fortress was impossibly grand, but when she was born there in 1926, the second child of Joseph and Nadezhda (“Nadya”) Stalin, the Russian Revolution was only nine years old. The public would always see her as the princess in the Kremlin, but her father’s Bolshevik discipline dictated a relatively modest life.

The Stalins lived in the old Poteshny Palace, a three-story building erected in 1652. It was known as the Amusement Palace and served as a theater for comic performances until, in the nineteenth century, it housed the offices of the Okhrana, the tsar’s secret police. The Poteshny retained its elegant theatrical chandeliers and carpeted staircase, up which the Stalins climbed to their gloomy, high-ceilinged apartment on the second floor.

Svetlana remembered that apartment: “There was [a room] for the governess, and a dining room large enough to have a grand piano in it. . . . In addition there was a library, Nadya’s room, and Stalin’s tiny bedroom in which stood a table with telephones.”

There were two rooms for the children (she shared hers with her nanny), a kitchen, the housekeeper’s room, and two bathrooms. Wood-burning stoves heated all the rooms. As she described it, “it was homely, with bourgeois furniture.” Families of other Bolshevik leaders lived across the lane in the Horse Guards building and casually dropped by.

In keeping with the ideology of the Party, there was no private property. Everything belonged to the state, down to the wineglasses and silverware, which meant, in the end, that everything was up for grabs. In the early days, even Party members had ration cards for food, but their use was hypothetical. In a country where the populace was starving, there was always enough food for the intimate soirees when the Party magnates gathered in one another’s apartments. All the leaders were assigned one of the country dachas abandoned by the rich upper classes who had fled in the early days of the Revolution.

When Svetlana was born, on February 28, she entered an already crowded household. Her brother Vasili had been born five years earlier, on March 21, 1921. The story went around that Nadya, demonstrating Bolshevik austerity and an iron will, had walked to the hospital after dinner to deliver her son. Once the ordeal was over, she phoned home to congratulate Stalin.

Svetlana’s half brother Yakov Djugashvili, the child of Stalin’s first marriage, had also joined the household in 1921. Yakov was nineteen years older than Svetlana and would become her champion until his brutal death in a Nazi POW camp.

Family life had a Chekhovian quality, with relatives wandering into and out of the Kremlin apartment. There were two branches of the family: the Alliluyevs and the Svanidzes. Nadya’s own family constantly visited. By now the large clan included Nadya’s parents, Olga and Sergei Alliluyev; her brothers, Fyodor and Pavel; Pavel’s wife, Eugenia (“Zhenya”); her sister, Anna; and Anna’s husband, Stanislav Redens. All the family members would come to play tragic parts in the Stalin narrative.

The Svanidze branch arrived from Georgia in 1921, shadows out of Stalin’s past. In 1906, when the Georgian-born Joseph Stalin was still just a local agitator fomenting revolution under the code name Soso, he married the sister of a school friend and fellow underground revolutionary, Alexander (“Alyosha”) Svanidze. In those prerevolutionary days, when the triumph of the Bolsheviks seemed impossibly distant, Svanidze’s three sisters ran an haute couture fashion house in Tiflis (Tbilisi), called Atelier Hervieu. The waiting room was always full of counts, generals, and police officers. While the sisters fitted the dress of a general’s wife in one room, the revolutionaries discussed their plans for sabotage next door and hid their secret documents inside the stylish mannequins.

The youngest sister, the exquisitely lovely Ekaterina Svanidze, whom everyone called Kato, fell in love with the mysterious and witty Comrade Soso. By then he was head of the Bolshevik faction in Tiflis, and it was no surprise that the tsar’s secret police often came calling. Kato was pregnant within months of their marriage and gave birth to Yakov in March 1907. She contracted typhus shortly afterward. The family reported that Kato, just twenty-two, died in Soso’s arms on November 22, 1907. At the funeral, a distraught Soso threw himself into the grave with the coffin, and then he disappeared for two months.

Stalin’s first wife, Ekaterina “Kato” Svanidze, who died in 1907.

(Svetlana Alliluyeva private collection; courtesy of Chrese Evans)