По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

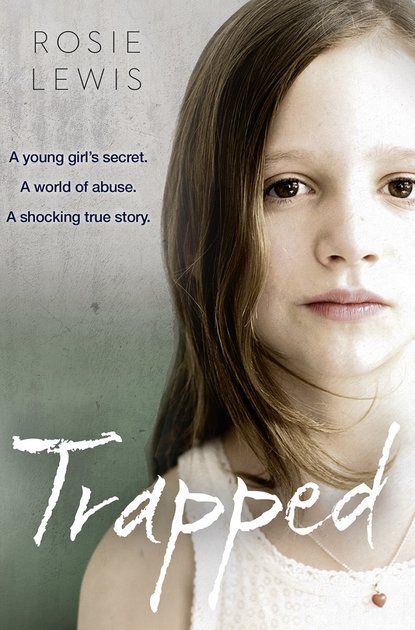

Trapped: The Terrifying True Story of a Secret World of Abuse

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Thankfully, I have managed to build a rapport with each of the children I’ve cared for in a short space of time, usually within a few days. As each relationship strengthened, I found that the claustrophobia ebbed away. The trouble was, with Phoebe, I just couldn’t see it happening. Down in the living room, I visualised the virtual calendar I had in my head; she would be gone before the end of the Easter holidays – one day down, 13 to go.

Chapter 5 (#udd7d0065-e7f4-5814-9c55-5a12939a45be)

The next morning I woke at just after 6am, feeling a bit more positive. Phoebe had slept right through the night, something I hadn’t expected at all. Most children struggled to settle for the first few nights in a strange bed and so I had been prepared for some degree of sleep deprivation.

Relishing the silence, I washed and dressed then pottered downstairs and made myself a coffee. Sitting at the kitchen table, I watched a pair of robins settling on the branch of our apple tree, their wings shining in the bright, early morning sunshine. The scent of winter jasmine floated through the open window, boosting my already lightened mood. As I sipped my warm drink, I dared to think that the placement might not be as difficult as I had first thought. With firm boundaries in place, Phoebe’s symptoms might not be so pronounced as they were on her arrival. I wasn’t that knowledgeable about autism but I had heard that routine went a long way in helping sufferers to cope with the everyday stresses that other children barely noticed.

And anyway, that was the nature of fostering; no one ever said it would be straightforward. Whatever the reason for their removal from home, fostered children arrive in placement at probably one of the lowest points in their lives. It’s not surprising that they may then ‘act out’ their unhappiness, perhaps by stealing food, money or items of sentimental value, destroying property, refusing to wash, being deliberately provocative, violent or aggressive, or more passively, wetting the bed or self-harming. But having a hand in helping a child to mend was hugely satisfying and certainly worth all the hardships along the way.

That’s not to say there is always a happy ending. It took me a while to accept that. Alfie, for instance, whose mother was imprisoned for a short period for his neglect, stayed with me about four years earlier, while a Care Order was secured through the courts. Members of his wider family were assessed and it was decided to award his grandmother special guardianship. I have since heard through the grapevine that Alfie’s mother left prison and went straight to live with her own mother in the flat where she cared for Alfie.

Within weeks a new young boyfriend had joined her there and recently grandmother (who hadn’t yet celebrated her fortieth birthday) fell for a roofer from Essex and spent long periods of time drinking with him in his bedsit in Hornchurch. I have known social services to spend two years and an inordinate amount of money securing a Care Order through the courts, only for the children to then return home via obliging friends or relatives. It’s not an ideal system.

It is sometimes said that foster carers are ‘in it for the money’. I find it difficult to believe that anyone could survive more than six months as a foster carer unless there was a powerful drive to ‘heal’ hurt children.

For one child, a foster carer’s ‘wage’ is around £200 per week, although this amount varies depending on the local authority. On top of that an allowance of between £60 and £100 is paid (depending on the age of the child), an amount that must be spent solely on the child and meticulously accounted for. Surviving on £800 a month can be a struggle, particularly in a one-parent household. With two children in placement, life is a bit more comfortable but certainly not luxurious.

I’ve never been driven by money; for me a happy home life and contented children holds far more value and so being able to just about manage was all I needed to be content. Fostering had given me many ‘I will never ever forget this’ moments, some of them for their awfulness, but others that were almost magical.

By 7.30am I was beginning to find the stillness unsettling. In my experience it was unusual for the under-10s to sleep in. Reluctant to disturb the blissful peace but unable to relax without checking on Phoebe, I crept up the stairs and along the hall. The smell hit me before I reached her closed door and I groaned, anticipating the scene before I had even laid my hand on the handle.

It was worse than I’d thought.

Retching as violently as Phoebe had done the evening before, I clamped my hand over my mouth and forced my feet to shuffle into the room, flicking the light switch on with my elbow. Phoebe lay serenely in bed, the duvet pulled up to her neck just as it was when I left her the night before. The room was considerably different, though: the magnolia walls were smeared with streaks of excrement, each lilac butterfly spattered with a generous coating of stomach-churning brown. Even the curtains hadn’t escaped Phoebe’s attention, with clumps of stinking excrement clinging to the fabric.

I couldn’t help myself: ‘My God, what have you done?’

‘My God, what have you done?’

That was it. I charged into the room and yanked the duvet away from her. Phoebe squealed, drawing her soiled hands up to her cheeks and rolling to one side. Curled up in a foetal position, she buried her face in her stained and smelly pillow. My fury ebbed away at the sight of her lying there, so thin and pitiful. Instantly I felt ashamed that I’d broken my promise by entering her room without being invited. Still panting in shock, I stared down at her, frowning. There was something different about her, though, and it wasn’t just the streaks of brown across her hands.

‘Phoebe, you need to get out of bed so I can clean you up,’ I said, my voice wobbling with the strain of keeping my feelings of revulsion under control. She pushed herself up to a sitting position, watching me warily. As she stood up I realised what had changed; she looked bulkier, as if she’d put on half a stone overnight.

‘What have you got on under those pyjamas?’ I demanded, wondering what other horrors might yet be uncovered.

‘What have you …?’

‘That’s enough,’ I shouted, my finger raised and pointing at her. ‘I don’t want you to copy me, do you hear? Now go to the bathroom, right now!’

Without warning she ducked and ran past me, out of the room. I tried to grab her but she was too quick, darting out of reach.

‘Phoebe, come back,’ I called, trying to sound firm but unthreatening. Holding my breath, I followed the brown prints her soiled feet had made on the cream carpet. The air smelt vile.

‘What’s all the noise, Mum?’ Jamie’s timing couldn’t have been more devastating. Bleary-eyed, he sauntered out of his room as Phoebe tore along the hall, holding out his hands in a defensive action as she flapped her arms through the air. His look of horror told me that he realised exactly what she was covered in.

‘Sorry, Jamie,’ I muttered, charging past him and, with damage limitation at the forefront of my mind, followed Phoebe down the stairs.

‘Urgh, she is sooooo disgusting!’ Jamie, usually so mild-mannered, wailed angrily from upstairs. ‘Come and have a look at her room, Mum.’

Ignoring him, I followed Phoebe into the living room, desperate to catch her in case she nursed an intention of sprawling herself out on one of the sofas in all her self-decorated glory. There was no sign of her there so I quickly scanned the dining area, half-aware of Jamie’s bewildered shouts of disbelief floating down from upstairs. ‘Mum, really, you’ve got to come and see this. You won’t believe what she’s done in here.’

‘Eww-urgh!’ Another horrified shriek announced Emily’s emergence from her room. ‘Mum, what’s happened to my butterflies?’

Phoebe was crouched in the corner of the kitchen, her face full of fear. She held her dirty hands protectively in front of her.

Ten minutes later Phoebe sat in the bath with the door open while I gathered together every cleaning product in the house to spray, squirt and obliterate the smell permeating each room. Jamie hunkered down in his room with Emily. I was pleased that they had chosen to recover from their shock together. The pair had always shared a good relationship and it seemed that bad experiences brought them even closer. I could hear their urgent chatter drifting beneath the closed door, low tones interspersed with manic giggles.

As I scrubbed Phoebe’s soiled room, I was gripped by regular heaving fits: it wasn’t only the acrid smell – every time I set about cleaning a new area, the mess spread. What it really needed was a power hose.

Every few minutes I stopped what I was doing and peered around the bathroom door to make sure Phoebe wasn’t feasting on anything she shouldn’t. After the ‘Bubble Gate’ affair I had cleared the bathroom of anything that wasn’t nailed down but there was a chance I might have overlooked something. For all I knew, even the bath plug might be adequate fodder in her eyes.

The hollow gaps above her clavicles were so deep with undernourishment that the bath water pooled there as she sat up. Resolving to try and tempt her into eating with double chocolate pancakes for breakfast, I leaned into the bathroom and, with reluctant, pincered fingers, picked up her discarded pyjamas from the floor. Her soiled knickers were knotted up with the legs so I tried to separate the items, realising there was far more than one pair of pyjamas in the tangled heap. Unravelling the clothes, I pulled out four pairs of knickers and three sets of bottoms.

A dismal, draining feeling crept across my skin as the memory of another little girl I had cared for broke the surface of my thoughts. Four-year-old Freya came to stay soon after I first registered as a foster carer seven years earlier, along with her younger sister and baby brother. She had a habit of wearing all of her clothes in bed, one layer on top of another. It was her way of trying to keep herself safe, should anyone pay an unwelcome nightly visit to her room, as her father had done.

Feeling nauseous, I stared at Phoebe’s fragile back, trying not to let past experience colour my perception. Foster carers, like social workers, can be prone to jumping to conclusions and piling on layers of clothing was not necessarily an indication of abuse; it could simply be yet another manifestation of her condition. ‘Phoebe,’ I said gently, holding up the smelly clothing. ‘Why did you wear so many pairs of pyjamas to bed?’

She stared at me blankly, so I decided not to make an issue of it. Stuffing the clothes into a carrier bag, I dropped it onto the floor. ‘Do you mind if I give your hair a wash, Phoebe? I won’t do anything else, just your hair. Is that OK?’

‘NOOO!’ she howled. ‘I hate having my hair washed.’

‘Yes, I can see that. But you need to have it done.’

My tone made it clear that refusing was not an option. Surprisingly, she sat motionless as I lifted the shower head and dampened her hair down, running my fingers over the stubby ends. It really was frizzy, almost Afro-style in texture. I reached up and unlocked a cabinet fixed up high on the wall and retrieved the shampoo, squeezing a generous blob into my palms. After rinsing the suds away I smoothed in some conditioner, trying to massage it all the way through to her scalp. The tightness of her hair seemed to loosen so I lavished another handful through, rubbing it in with my fingertips.

Phoebe wriggled away, whimpering.

‘Keep still or you’ll get conditioner in your eyes,’ I said. As I massaged and rubbed her scalp, the texture softened beneath my fingers. Strangely, the tendrils seemed to be extending, like the hair of one of those dolls that Emily had years ago, where the style could be altered by winding a ponytail in and out of the head. It was then I realised her hair wasn’t as roughly chopped as I had first thought; it was actually matted.

‘Owwww!’ Phoebe began to howl.

‘It’s alright, you’re done now,’ I soothed. I wasn’t surprised she’d been moaning – it must have been very uncomfortable. There were still balls of matted hair clumped to her scalp and I was itching to sort them out but I decided to rinse her off and tackle it again next time. Leaving Phoebe to dry herself, I grabbed the bag of soiled clothes and went downstairs to prepare breakfast, wondering why on earth any mother would leave her daughter’s hair to get into such a bad state.

Phoebe managed to eat a few mouthfuls of porridge before clanking her spoon onto the table. Leaning forward to rest her elbows, she cupped her chin in her hands and watched the rest of us tuck into our chocolate pancakes with a look of sickly distaste on her face. She really seemed to derive no pleasure from eating, or anything else, come to think of it. Despite her middle-class background she looked malnourished, her cheeks the colour of frozen pastry and her eyes dull and lifeless. She had that look that children seem to get the day before a cold comes out, where their eyes just don’t seem right.

After clearing away the breakfast things I packed up my manicure set and hairdressing scissors and told Phoebe we were going to visit a friend of mine who needed some help. The friend was actually an ex-neighbour who was elderly and unable to get out and about as she once did. Apart from one son there was no one else to help her so I paid her a call once a week to give her hair a wash and tidy the house. Once or twice over the last couple of years I had made the suggestion that her son might consider running some of the errands himself but each time I broached the subject he shuddered, declaring old age made him nauseous.

Today Mary had requested a haircut and foot manicure, something I wasn’t looking forward to with any relish, but it was a relief to escape the gloomy confines of the house. Before we left I suggested that Phoebe choose a book to take with her and I was surprised to find what an interest she showed in selecting one. While she scanned our bookshelves there were no strange whirly arm movements or whooping noises; she just ran her fingers across the spines, pulling one out every now and again to examine the cover. I was also a bit taken aback by the one she finally settled on: Roald Dahl’s The Giraffe and the Pelly and Me. I wasn’t sure she’d be able to manage it and was wondering whether she chose it for Quentin Blake’s colourful illustrations alone, when she read the blurb out loud, inflecting parts and showing real expression. Amazed, I chastised myself for jumping to conclusions and underestimating her.

With an interest in reading, I hoped that Phoebe would behave and let me get on with sorting Mary out. And I was grateful to find that she did. Apart from exclaiming when we first arrived that the house ‘stinks’ and that Mary’s toenails looked like ‘dirty old twigs’ she simply sat reading her book and looking up occasionally, watching us with interest. It was a joy to witness her animated face as she read. There were lots of smiles interspersed with gasps and sudden bouts of giggles. I made a mental note to take her to the library so that she could choose from a wider range of books.

Soon after we arrived back home I suggested a walk to the local shop. ‘You could have a look around and see if anything takes your fancy for lunch,’ I said, hopeful that if I gave Phoebe a small trolley she might gain a bit more enthusiasm for food, the way children often do when they feel involved.

‘Hwah.’ Phoebe instantly gagged at the thought.

‘Alright, not to worry,’ I soothed, assuming all the emotion had upset her system. ‘I’ve got to get some milk anyway.’

Jamie looked revolted by the sounds Phoebe was making, watching her with his lip curled in disgust.