По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

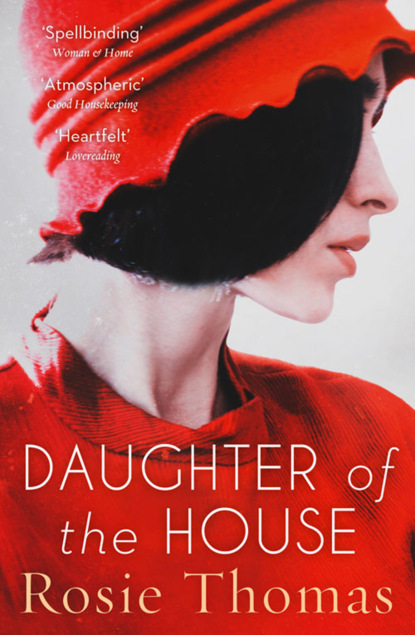

Daughter of the House

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘He believes that you can help him to speak to Mrs Clare.’

Nancy’s dry lips cracked and made her wince. ‘But Mrs Clare is dead. And Phyllis and Mr Clare and the little girl.’

‘Yes, very sadly that is true. Unfortunately, Mr Feather can’t reach his late sister on the other side or hear her messages himself, despite his skills. He believes that you will be able to do this for him. Under his control, that is.’

There was a silence. Lawrence Feather’s eyes implored Nancy. She sank lower in her chair.

Eliza asked, ‘Do you think you can do this, Nancy?’

‘No.’

The monosyllable dropped into stillness. With a stage artist’s timing Eliza let the silence gather and deepen. At last she said, ‘There you are. You asked to be allowed to consult my daughter, and against my preference you have been able to do so. You have your answer, Mr Feather.’

He started forwards in his chair. ‘Nancy, please listen to me. You and I both know …’

Eliza cut him short. She stood again, ignoring the pains in her back. Her demeanour was so forbidding that the medium fell silent.

‘There’s nothing more to be discussed.’

She crossed to the door and held it open.

Only when she had seen him out of the house and watched him walking to the tram stop did she return to Nancy. The girl was hunched in her chair, her arms wrapped around herself. Eliza believed the child was telling the truth – she was too obedient to do otherwise – but the afternoon’s events were still troubling.

‘What nonsense. The poor man must be unbalanced by grief.’

Nancy raised her head. ‘Perhaps,’ she said.

Her gaze seemed clouded, no longer quite that of an innocent child.

‘I ask you one more time, Nancy. Are you quite sure that nothing untoward happened with that man? Did he touch or even speak to you in any way that was improper?’

Nancy’s face flooded with colour.

‘No, not at all.’

‘Then why does his presence trouble you? It’s obvious that it does.’

‘I’m not denying it, Mama. He is strange, and to see him makes me think of the steamer and Phyllis.’

It was an oblique version of the truth and Nancy reddened at even slightly misrepresenting herself to her mother.

Eliza considered. Nancy wasn’t an actress, she couldn’t feign distress so convincingly. The Queen Mab had been a shocking experience for all three children, and it was natural for Nancy to be upset by the reminder. She put her arm around her daughter’s shoulders.

‘I understand.’

Eliza and Devil had decided that they should not dwell on the circumstances of the tragedy. In their own experience the best way to deal with shocking events was to leave them in the past. She hugged Nancy briefly and then released her.

‘You will not have to meet that man again.’

‘Mama?’

‘What is it?’

‘Is there such a thing as psychism? Can the dead speak to us?’

Eliza hesitated. It was a long time since she had been able to command the reverie. Long ago, by emptying her mind on an exhaled breath, she had been able to slip into a peaceful dimension of intense colours. She had been a rebellious child, and she had used the ability as a shield against adult wrath and a refuge from tedium. Later when she had taken employment as an artists’ model, she had made professional use of the reverie to hold her pose in the life-drawing class.

The power had gradually deserted her at about the time she fell in love with Devil, and she supposed now that the condition had been connected with the physical and emotional changes of young womanhood. She had never heard voices from the other side, and she was sure that her innocent reverie was no channel to the supernatural.

Devil had been the one who claimed that he saw ghosts. But then Devil had suffered such hardships and horrors during his childhood it was hardly surprising his imagination had turned macabre. Yet he too had grown out of his susceptibility. He had not spoken of his ghosts for many years now.

Eliza considered herself to be a rational woman with modern ideas. Her scepticism was founded in years of exposure to the tricks and devices of stage illusionists.

‘No, the dead do not speak to us,’ she answered at length. ‘But as you already know there are some people who claim they do.’

‘Why do they do that?’

She patted Nancy’s hand. The naivety of the question reassured her. It was time to finish this conversation and move on to healthier topics.

‘For money, or perhaps for public attention,’ she smiled. ‘Now, look at the time. You should go and dress, or we will be late at Aunt Faith’s.’

Nancy went upstairs. Across the landing, in the larger front bedroom shared by Cornelius and Arthur, Arthur’s school trunk and boxes were packed and corded ready for the carrier. Tomorrow, Devil and Eliza would drive their son to Harrow School in the De Dion-Bouton. The motor car had been polished to a state of glittering perfection by old Gibb, the chauffeur-mechanic Devil had employed to look after it.

In contrast to his brother’s success, Cornelius had recently become a clerk in a shipping office. Every day he carried sandwiches packed in a tin box to his place of work and he had described to Nancy how he sat on a bench in a nearby graveyard to eat them.

‘I like it. It’s peaceful.’

He dismissed all questions about his colleagues or the actual work he performed, but this surprised no one. Cornelius was never communicative.

Nancy leaned on the windowsill, as Lizzie had done when she smoked the startling cigarette. From here she could look straight down into the basement area where the mangle stood under its tin roof. A little iron bridge led from the dining room across to the garden where Eliza liked to grow flowers for their fragrance. The strong perfume of night-scented jasmine was already drifting upwards.

She hadn’t confided in her mother. She had the not altogether unpleasant sense of having cut her moorings.

She had said No to Mr Feather because it was true in the broad sense. She didn’t think she could speak to Mrs Clare.

Yet she did know that there had been an unnatural relationship between Mr Feather and his sister. Helena Clare had been afraid of him; Nancy had clearly seen it in her face. Instead of the garden lying below her she saw a boathouse and a moored boat with cushioned seats. Outside, shafts of greenish light struck across lake water and in the shadowy interior two bodies grappled and then locked together. The rowing boat violently rocked. She was witnessing something horrible and wrong, and she was disgusted as well as afraid.

It was a mild evening, still early, but the hairs on Nancy’s forearms rose.

She drew her head inside and slammed the window on the Uncanny. An unexpected glint of light on metal caught her eye and she crossed to her dressing table to see what it was. Lying next to her hairbrush was a silver locket she had never seen before. The chain was neatly folded but it was tarnished, as was the locket itself. She picked it up and cupped it in the hollow of her hand. There was a faint design of engraved leaves on the front and traces of dirt caught in the filigree. Unwillingly, she turned the piece over.

The initials engraved on the reverse were HMF.

Her hand shook but she slipped her thumbnail into the crease between the halves of the locket and prised it open. Within lay two locks of hair, twisted to form a ring and bound with scarlet thread. The tiny circlet was damp and earth was matted in it.

She closed the locket and dropped it on the dressing table. She knew whose initials these must be, and whose heads the two locks of hair had come from.

Arthur raced up the stairs, his boots skidding on the linoleum. He drummed on Nancy’s door.