По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

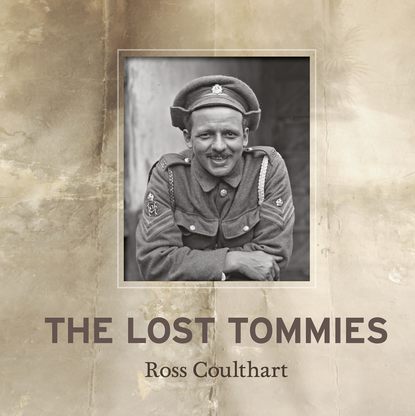

The Lost Tommies

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

PLATE 32 Labour Corps.

PLATE 33 Royal Army Medical Corps.

PLATE 34 Royal Engineers.

PLATE 35 Dorsetshire Regiment.

Identifying the Tommies (#ulink_0ca1c135-2b78-596a-81a0-fda0b20cb97c)

PLATE 36 A sad soldier of the Royal Fusiliers – a close-up from the high-resolution scan of his fatigued face shows him lost in thought. This same soldier also appears in Plate 216 (#litres_trial_promo).

In February 2011, the Australian Channel Seven TV Network aired a documentary about the discovery of the Thuillier glass plates. Shortly after that ‘Lost Diggers’ story was broadcast, we posted thousands of the Thuillier collection photographs of the Allied soldiers on the programme’s website and also on a specially created Facebook page, which still exists today. It became an unprecedented social media phenomenon for a history archive, with millions viewing the pictures online from all over the world. Within days, the volume of emails, excited phone calls, letters and Facebook messages we were receiving showed just how much the images had touched so many. Hundreds of thousands of viewers wrote us emotional and passionate accounts of their response to the faces of the Australian diggers and British Tommies in particular:

Goose bumps watching the show …

This is so wonderful, I can barely believe it’s true. Many of the faces showed signs of great fatigue and yet they managed to smile and pose for a photo forever preserving the moment in time …

A few tears shed knowing some of these fellows never made it home. What a wonderful discovery for many families around the world.

For so many of the people who have since viewed the photographs online it has become a personal odyssey to find a connection with the as yet unidentified soldiers:

These photos brought tears to my eyes. I had eight great uncles who all fought on the western front. Five of them were brothers. One of them was killed in action five weeks before Armistice Day, after surviving three years of that bloody hell. He is our only Digger out of eight that we have no photographic record of. Maybe he is one of these men.

Thank you so much for making these great photographs available. My mother lost her uncle in France in 1915. We have no info’ on him, not even a photo. We have always tried to find his records but without a regiment number, we are up against a brick wall. I sit here with tears in my eyes, wondering if he is one of these brave men. You have done a wonderful thing.

Our grand uncle … died of wounds … How amazing to think his image could be among these photos.

I carefully examined each and every photo looking for any resemblance to the many family members who fought in WW1, some of whom never returned.

Then began the calls for the Australian images to be brought home:

Don’t let them be forgotten. Bring these historical plates to their rightful home.

These photos … should be treated as national treasures and every single one of them should be brought home immediately.

These young men gave their lives in order to protect and fight for our country; these photos are an amazing part of the history of Aussie diggers in battle and the campaign they were involved in … Lest we forget.

Many relics of these men may remain in France but these treasured photos need to be honoured on Australian soil. It is now our turn to answer the call of duty and return these photos to their home for safekeeping.

Ohh I have tears of pure joy and total sadness after looking through these pics … History in front of our very own eyes … Thank you for sharing. Never forgotten.

In July 2011, with the generous support of the Seven Network’s chairman, Kerry Stokes AC, the entire Thuillier collection of around 4,000 glass photographic plates, including the British images, was purchased from the living descendants of Louis and Antoinette Thuillier, the couple who had supplemented their farming income during the First World War by selling pictures to passing Allied soldiers. If Louis and Antoinette were alive today they would no doubt be chuffed and probably very surprised to see just how much passion their portraits of thousands of young soldiers from a war so long ago has aroused.

PLATE 37 An equally sad-looking soldier – no regimental badge.

In late 2011 the precious glass plates did finally ‘come home’, in a gigantic packing case, purpose-built to carry them, along with the Thuilliers’ canvas backdrop. After months of planning, cataloguing, careful cleaning and scanning, the Australian digger plates were gifted to the Australian War Memorial for permanent display. Many of the more intriguing images and the stories behind them formed the basis of a nationwide touring photographic exhibition organized by the AWM. The remaining thousands of British and other Allied soldier plates have been preserved by the Kerry Stokes Collection in a secure repository in Perth, Australia.

More than once in our research it has struck us how impermanent many of the records that we rely on today are in comparison with the handwritten files, letters, printed photographs and glass photographic plate negatives that have made this such a rich collection. As we began examining the plates, drawing on the expertise of people like Peter Burness, it was a revelation to discover how, in many ways, the photographic plates used by the Thuilliers are actually a superior storage medium to the standard celluloid photographic negative, let alone digital imaging. Not only have they already lasted nearly a century, but so much information is packed into these enormous negative plates that it was often possible for us to zoom in on a colour patch, medal ribbon or cap badge to help identify a soldier. There is something terribly poignant about being able to zoom in to the pained and weary eyes of an individual soldier – actually to see the mud on his boots and the texture of his uniform.

As we applied modern photo-processing software, it was astonishing to see faces emerge from the murk of so many plates – images that could so easily have been lost forever. We have asked ourselves many times how much of today’s history will survive to the same extent. How many personal handwritten letters have we preserved today that will record the thoughts and experiences of our loved ones for future generations to read? What was once recorded in a letter just a few decades ago is now just an electronic impulse stored on magnetic media whose lifespan can still currently only be surmised. Will the digital records of today – the photographs, emails and the writings on other online ephemera such as Facebook, Twitter and websites – allow people in a hundred years to explore the history of our present era with as many resources as remain from the First World War? How much of our heritage and experiences will be lost as contemporary storage media slowly fade or are carelessly deleted?

The process of identifying, at least by regiment, as many of the Thuillier images as possible for this book has been a painstaking and often frustrating process. Many of the soldiers were photographed in front of the distinctive painted canvas backdrop and that has been a useful fingerprint in identifying Thuillier pictures which made their way back home into family collections or regimental history books. On rare occasions the identification was easy because a particular soldier features and is actually named in one of the rare Thuillier images reproduced in regimental history books or contained in personal collections. There have been other occasions where photographs taken of soldiers after the war have allowed us to ‘match’ them with a soldier in a Thuillier image (see the Royal Fusiliers). Once identified, it has also been difficult to find out more about a particular soldier because so many of the British service files are incomplete or were destroyed completely in German bombing raids during the Second World War.

PLATE 38 An unidentified soldier. No clues as to his regiment can be seen in the photograph.

The Backdrop (#ulink_cf0fdb2d-e579-5fce-9b19-6ead46e43b5c)

One of the key clues that helped us track the Thuillier collection was the distinctive backdrop that appears behind soldiers and civilians in many of the pictures. Well before the discovery of the Thuillier portraits, historians at the Australian War Memorial had noticed the length of painted canvas in a handful of images of different soldiers held in its collection, and they were excited by what it implied. If a photographer had taken the trouble to paint a backdrop for posed photographs somewhere behind the front line, maybe there were more to be found than the dozen or so that had made their way into official collections.

PLATE 39 An excellent Thuillier image showing how the backdrop was used – the soldier is probably from the 6th (Inniskilling) Dragoons.

Never did we think it possible that the backdrop used by Louis and Antoinette Thuillier could have survived nearly a century in a dusty attic. But, as we fumbled around in the eaves of the family attic in Vignacourt back in early 2011, we found, wedged between two roof beams, a tight roll of canvas mounted on a wooden pole. Eager to see what was inside, but anxious not to damage it, we lugged the dusty canvas roll down the three flights of stairs to the courtyard … and gently unrolled it.

PLATE 40 Unfurling the backdrop. (Courtesy Brendan Harvey)

It is a little damaged from its near-century in a draughty attic, but the distinctive double archway seen in many of the photographs is still clearly visible.

PLATE 43 Close-up of the backdrop. (Courtesy Brendan Harvey)

There are hundreds of photographs in the Thuillier collection which clearly predate the painted canvas backdrop – many of them are probably pre-war images of French civilians and then, when war broke out in 1914, they feature the French soldiers who used the town as a staging post before they headed up to the front lines. As business picked up, Louis and Antoinette must have decided that a painted canvas backdrop offered a more professional look for their clients and so the first images using the backdrop began to appear.

PLATE 41 An early Thuillier photograph of a French second lieutenant, of the 4th Colonial Infantry Regiment, and his wife, without the distinctive backdrop. Likely to have been taken sometime in July 1915 when the French 1st Colonial Corps was billeted in Vignacourt.

PLATE 42 A French soldier and his family in front of the distinctive Thuillier canvas backdrop.

PLATE 44 A soldier poses in front of the Thuillier backdrop, using a chair as a prop. The distinctive high table used in many other photographs can be seen just to the left. This soldier has two good-conduct chevrons on his lower left sleeve, indicating that he has six years with a clean record of service on his army record.

PLATE 45 A soldier from the Royal Engineers. His armbands show he is a qualified signaller. Possibly taken when the engineers were in and around Vignacourt in early 1916 preparing transport links and hospitals for the Somme offensive.

PLATE 46 Soldiers of the Royal Artillery Regiment, two with good-conduct chevrons. Clearly Thuillier moved his backdrop according to the state of the weather. The soldier in Plate 44 (#ulink_99bcd87b-b06a-5819-a0eb-7959a1db9c5e) stands on a smooth cement floor in a covered area. This image is taken outside on cobblestones. It seems likely the smoother-floored area was used by Thuillier later in the war – hence this image predates Plate 44 (#ulink_99bcd87b-b06a-5819-a0eb-7959a1db9c5e). However, the tunic worn by the soldier seated left is an ‘economy tunic’ without pleated pockets and without the rifle patches over the shoulders – which was issued only in 1916.

THE VIGNACOURT BREAD BOY (#ulink_afb84022-44d7-5ff7-b9ed-1b4599e3d228)

The discovery of the Thuillier glass plate images has been as moving for many of the villagers of Vignacourt as it has been for the numerous families who have searched for their relatives among them. In November 2011 hundreds of townsfolk came to Vignacourt’s town hall to view the two Australian Seven Network television documentaries that had been produced at that time on the ‘Lost Diggers’, subtitled in French for the occasion. For the village it was a chance to learn more about a chapter in the region’s history that only a few of the elderly villagers still recalled. Around the walls of the town hall, many poster-sized prints of some of the iconic Thuillier photographs also drew an excited response. For even after nearly a hundred years, some Vignacourt families were excitedly identifying their loved ones among several of the pictures taken of civilians during the conflict.

The young lad in Plate 47 (#ulink_fdcad0ac-f181-55ff-8c72-16c3f3cf688a) was recognized by his family as Abel Théot. At the time this photograph was taken by the Thuilliers, the boy’s life was one of hardship and sadness brought about by the war. Abel was one of five brothers, two of whom died fighting in the French army against the Germans. His father was away at war, too, and Abel sold bread and pastries to Allied troops to bring in extra money to help his mother and family survive. Tragically, after this photograph was taken, Abel learned that his father had also died in the fighting; another of his brothers returned with serious wounds.

PLATE 47 Abel Théot, the Vignacourt bread boy.

How the Thuilliers Took Their Photographs (#ulink_4d1d3971-807e-59f7-8466-ef480b73862f)

It was another Frenchman, Louis Daguerre, who had invented one of the most important precursors of modern photography, the daguerreotype, in the 1830s – the Polaroid of its day. The daguerreotype produced a single image, which was not reproducible. In the 1850s, more than sixty years before the outbreak of the First World War, William Henry Talbot devised the negative process in which a glass plate negative allowed any number of prints to be made. But the glass plate technology came under threat from the nascent celluloid film cameras produced by Kodak in the late 1880s. By the outbreak of the Great War in 1914, black and white box brownie cameras were relatively common and it is intriguing to speculate just why Louis and Antoinette Thuillier did not opt for the much cheaper film cameras that were by then available. Perhaps the pair were purist professional photographers – and there were many right up even to the 1970s – who continued to favour glass plates because of concerns that the early celluloid films could not provide the sharp images so beautifully rendered by the older glass plate negative technology. Glass plates are still used for photography today in some scientific applications. The problem of sharpness in the early celluloid film cameras was caused by the poor lenses; and nor could early film camera technology provide a sufficiently reliable flat focal plane compared with that provided by a glass plate camera. This was because the celluloid film, although stretched across the back of the camera, still curved slightly and this made for less crisp images. All the better for amateur historians a century later, because the glass plate negatives used by the Thuilliers allow for an extremely high-quality print in comparison with the old celluloid film negatives, most of which have degraded to the point where they are unusable.

PLATES 48–49 An example of the high resolution possible from modern scanning of the Thuillier plates – the date on the Parisien newspaper in this elderly Frenchwoman’s lap can be read in the close-up image. Translated, it says either ‘Tuesday, 4 May 1915’ or ‘Tuesday, 14 May 1918’.

Another good reason for photographers like Louis and Antoinette Thuillier to use glass plates could have been one of economy: they had the option to reuse the glass plates once they had developed them and sold the positive prints. Reusing a plate would have simply entailed cleaning off the silver image on it. But the Thuilliers clearly kept most, if not all, of the plates they shot. What is exciting about this is what it suggests about their motives for taking the photographs in the first place. For if Louis and Antoinette Thuillier had only cared about their portrait subjects as commercial transactions, they could easily have recycled the plates once they had sold each soldier his picture. For whatever reason, Louis and Antoinette preserved the exposed plates; and, by the look of it, they kept nearly all of them, filling their attic with thousands. It is possible they realized the wartime portraits they were taking would one day be of enormous historical significance and worth. Even today in the Thuillier family attic there are sections of what appear to be old glass window plates from which Louis and Antoinette had cut glass in the size and shape of negatives. Glass was clearly so precious a commodity during the war that they were removing it from windows to fulfil demand.

PLATE 50 A French cavalryman of the 1st Cavalry Division writes a letter to his family on 20 June 1915.