По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

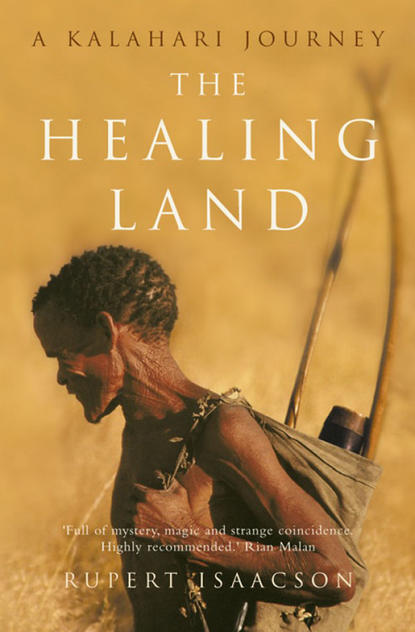

The Healing Land: A Kalahari Journey

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Then one day, out of the blue, a distant Loxton cousin from Australia wrote to my mother, saying that he had spent ten years researching the family and now wanted to put all the clan back in touch with each other. Among his researches, he had traced the Baster Loxtons, the coloured branch of the family, to a wine farm outside a small town called Keimos, at the southern edge of the Kalahari.

It seemed that they had prospered, and had, against the odds, managed to hold onto their land all through the apartheid years despite several attempts by the white government to dispossess them. Their farm, Loxtonvale, extended along several islands of the great river, where the original Baster kapteins had established their stationary pirate strongholds. Gert and Cynthia Loxton had transformed the islands into vineyards and orchards where they produced Chardonnay and sultana grapes and fruit. They also had a cattle ranch up in the southern fringe of the Kalahari.

My mother got the necessary addresses and flew out that year. When she returned, the link between the two sides of the family had been restored. And between these coloured Loxtons and the Taylors (my mother also visited Frank Taylor on that trip and reported that his Veld Products Research organisation was thriving), it seemed that the door to the Kalahari had finally opened a crack.

In 1992, I returned once more, having landed a contract to write a guidebook to South Africa. During my first week back in the country, I visited the Cultural History Museum in Cape Town, where eerie life-like casts of Bushmen (taken from real people, said the plaque) stood on display behind glass as if living people had been frozen in time. As I travelled I read, learning for the first time the proper history of these, the first people of southern Africa, whom academics called ‘KhoiSan’, but whom others called ‘Hottentots’ or ‘Bushmen’.

Many geneticists and anthropologists, I learned, considered the KhoiSan to be the oldest human culture on earth, possibly ancestors to us all. What was certain was that for thirty thousand years, perhaps longer, they had populated the whole sub-continent, pursuing a lifestyle that included hunting, gathering, painting, dancing, but not, it seemed, war (no warrior folk-tales, weaponry or battle sites exist from this time). Then, sometime around the first century AD, the warriors had arrived – black Africans, whom the academics called ‘Bantu peoples’ – migrating down from west and central Africa with livestock acquired, it is thought, from Arab traders in the Horn and the north of Africa. By the Middle Ages these ancestors of the modern nations of MaShona, Zulu, Ndebele, Xhosa, BaTswana and Sotho had pushed the Bushmen out of most of southern Africa’s lushest areas – what is now Zimbabwe and eastern South Africa. They kept Bushman girls as concubines and adopted some of the distinctive clicks that punctuated the KhoiSan languages. Rainmaking ceremonies and healing practices were also absorbed into the new dominant culture. By the time the first whites settled the Cape in the mid-seventeenth century, the Bushmen had vanished from almost everywhere except for the more rugged mountain ranges and the dry Karoo and Kalahari regions.

Some Bushmen clans, however, took on the culture of the invaders, adopting warrior traditions alongside the herds of cattle and fat-tailed sheep. These peoples – the Khoi or Hottentots – first traded with, then fought, the white settlers, confining the colony to a small settled area around modern-day Cape Town for a generation until successive waves of smallpox in the early eighteenth century so reduced the Khoi that they became absorbed into a general mixed-race underclass known today as ‘coloureds’. Only one group of Khoi survived into modern times – the Nama of northwestern South Africa and southern Namibia.

Having colonised the Cape, the white settlers began pushing north into the Karoo. Extermination and genocide followed, until by the twentieth century Bushmen survived only in the Kalahari. Now even these remote people, as I already knew from Frank, were under threat from the steady encroachment of black cattle ranchers.

As the year drew to a close, I travelled up to the southernmost edge of the Kalahari, where it reaches down into South Africa in a dunescape of red sands tufted with golden grass, and dry riverbeds shaded by tall camel-thorn trees. Even here, I was told, no Bushmen had been seen since the 1960s, maybe earlier. The crisply khakied reception staff at the Kalahari Gemsbok National Park – a narrow tongue of South Africa that makes a wedge between Namibia and Botswana – pointed vaguely northwards into the shimmering, heat-stricken immensity beyond the reception building and told me that I would have to go ‘deep Kalahari’, beyond the park even, if I wanted to see Bushmen.

Once again, it seemed, the gentle hunters of my childhood stories were going to remain just that – fictional characters. Instead, Africa had another kind of experience lined up for me. The year from 1992 to 1993 saw the lead-up to the elections that would change South Africa for ever. Anger that had been seething for generations was starting to erupt. I was researching the Transkei region, down in South Africa’s Eastern Cape Province, at this time still one of the ‘tribal homelands’, a region set aside for rural blacks – in this case the Xhosa – to live their traditional lives far away from white eyes. Overcrowding, overgrazing and therefore poverty were the predominant facts of life. Resentment was rife everywhere, but especially so in the Transkei: between the late eighteenth and the late nineteenth centuries, the Xhosa people fought and lost no fewer than nine consecutive wars against the Dutch and the British, forfeiting almost their entire territory in the process. Finally, in despair, all but three clans of the great tribe slaughtered their herds and destroyed their stores of grain, hoping that by this sacrifice their warrior ancestors would rise from the grave and drive the hated white men into the sea. But the ancestors did not come.

This humiliation only whetted the Xhosa’s determination to ultimately win out and beat the white man at his own game – politics. Many black South African leaders, including Nelson Mandela, came from the Transkei. During that pre-election year the region became a focus of anti-white feeling. One night, while in a beach-side rondavel

(#ulink_4607c5ad-ba34-5eea-a14d-2f37d0d2345a) down on the ‘Wild Coast’, Transkei’s two hundred kilometres of beautiful, sparsely inhabited strands, I woke with a start to see a man coming through the window holding a large kitchen knife. As if in a dream, almost without registering that I was doing it, I was out of my sleeping bag and pushing the intruder backwards, so that he fell the few feet to the ground outside with a muffled thud. Still in my dreamlike state, I put my head out of the window to see what was happening. There was a flicker of movement from the left – I jerked back just in time. His friend, who had been pressed against the wall, swung a knobkerrie, missing my head but hitting my shoulder hard. In an instant the mattress was off the bunk and pressed against the window, and the bunk frame was against the door. The bandits thumped and stabbed at both, but there was no way they could get in.

A few days after the attack, I headed back to the Transkei capital, Umtata. Coming out of the store, both hands laden down with shopping bags, I found my way blocked by a large crowd. It was the end of the day and the city’s workers were thronging the main streets, waiting for the minibus taxis that would take them home to their houses on the edge of town. While I was walking through the mass of people, a man approached me, asking the time and, before I could react, had me around the neck while several other hands grabbed me from behind. It was a nasty mugging, the frightened onlookers standing by, pretending nothing was happening, while the fists bloodied my face and mouth and the attackers shouted ‘White shit!’

A week after that, in Pietermaritzburg, Natal – a small, handsome city of red-brick and wrought-iron colonial buildings – I found myself in the midst of a riot. Chris Hani, the head of the South African Communist Party, which had strong links to the ANC, had been shot dead a few days before by a white supremacist. A nationwide series of ‘mourning and protest marches’ was planned and, though I had seen the warnings on television, I forgot and ended up driving downtown on the scheduled day, intent on picking up my poste restante mail. The streets, usually jammed with commuter traffic, were strangely empty. Turning into Longmarket Street, I felt a little glow of satisfaction at being able to park directly outside the ornate, pedimented entrance to the post office. I stopped the car and got out, slamming the door. Then I heard it. ‘HAAAA!’

I looked around and saw, some two hundred yards up the wide street, a wall of armed Zulu youth approaching at a run. Smoke and licks of flame billowed out from the buildings as they came. ‘HAAAA!’, the shout went up again, and in a flash I remembered the news warning. How could I have been so stupid? I had about thirty seconds in which to make a decision. The car, as bad luck would have it, was having battery problems, so I set off down the street at a sprint, but after just a few paces a door opened on my right and a hand beckoned. It was a bakery-cum-takeaway-shop whose staff had for some reason decided to ignore the news warning and open for business. There was no time for explanations, only to duck down with my saviours behind the counter. The first wave of the crowd swept by, roaring. I risked a look over the top of the counter, just in time to see the shop’s large, plate-glass window explode inwards. Shattered glass, stones, bricks and broken wood flew everywhere. Something sharp hit me on the shoulder, tearing my shirt and leaving a light gash on the skin. I ducked down again, then thought of the car with my laptop in the boot. I got up tentatively from behind the counter and walked out into the crowd of young men, all in their late teens and early twenties, who were milling about, as if deciding what to do. This was the second wave; few of them were armed, as the first, most destructive rank of rioters had been. These second-rankers were less angry, more bent on mischief. It showed in their smiles and the alert, slow-walking set of their bodies. A small group of young men with more initiative than the rest were looting a clothing store on the other side of the street, and that drew most of the crowd’s attention. However, standing around my car was a small knot of youths. Walking up to them I had the odd sensation of watching myself from outside my own body. ‘Morning, morning,’ I said, cheerily, stepping between two gangly teenagers dressed in expensive-looking sweatshirts. They did nothing, merely stood by as I unlocked the door, got in and fired up the engine first time. Waving jauntily, I slipped the clutch, rolled slowly forward and – to my amazement, and probably theirs – the youths stepped aside to let me go.

The volume of people, however, forced me to follow the direction of the crowd. After a couple of minutes, I was back among the first wave of rioters. Here, the street was in mayhem. Most of the youths were brandishing spears, ox-hide shields and kerries and shouting and smashing shop windows – some of them were throwing molotovs into the interiors. I was noticed almost immediately. A tall youth, holding a large rock in both hands, was staring around, looking for something to do with it. When he heard the car engine and turned to see a whitey sitting right in front of him in a car, his eyes opened wide and he made ready to smash the rock through the windscreen on top of me. I looked up at him, making pleading gestures with my hands. The car was still. We locked eyes for a couple of seconds, then abruptly he lowered the rock and gestured with his thumb down the street, shouting ‘Go!’

I sped off, a couple of rocks bouncing loudly but harmlessly off the car roof, but the end of the street was blocked by a wall of young men, making a human chain, presumably waiting for the riot police (and news cameras) to arrive. A shower of rocks greeted my approach, though only one connected, hitting the car bonnet and rolling off. I slowed down, searched for someone to make eye contact with, found a gaze in the human chain and held it with my own, taking my hands off the wheel and making the same pleading gestures as before. It worked. After a moment’s hesitation, in which another two rocks hit the car, the man – who was older than the others, perhaps in his mid-thirties – slipped his arm from the man next to him, made a space in the line and gestured for me to go through. I saw him mouth the words, ‘Quickly, quickly’. The ranks behind grudgingly made way, striking the car with hands, weapons and shouting ‘Kill the Boer! One Settler One Bullet!’ But they let me through. Once on the other side I floored it until I was out of the town centre and making for the suburb where I was staying, listening to the noise of police sirens and helicopters heading back towards the trouble. Later that day, I learned that several people had been killed by the mob.

So many violent incidents followed that year of 1993 that they began to blur into one another. By the time my year was up I had not only failed, for the third time now, to get to the Kalahari, I had not even managed to make contact with my coloured Loxton relatives. Instead, I returned home to London exhausted, feeling that I had run out of luck, doubtful if I would ever return to the land of my fathers.

Eighteen months later, however, I was back, this time to write a guidebook covering the three countries just to the north of South Africa: Zimbabwe, Botswana and Namibia. By then, 1995, the memory of those violent times in South Africa had faded a little, and my determination to find the Bushmen had reasserted itself. After all, the three countries I had to cover encompassed most of the Kalahari.

This time I was not travelling alone, but with my girlfriend, Kristin, a Californian. By a happy accident we managed to borrow a Land-Rover, the vehicle necessary for penetrating Bushman country. There were to be no detours this time. We picked up the vehicle in Windhoek, the Namibian capital, just around the corner from the Ausspanplatz, the town square where, as a boy, my grandfather Robbie had earned pennies by holding the horses of the farmers when they came to town. Two sweaty driving days later, we arrived at the tiny outpost town of Tsumkwe in Eastern Bushmanland, gateway to the ‘deep Kalahari’.

I had been told, during that previous trip to South Africa, that if you drove about fifteen kilometres from Tsumkwe, you would see some big baobabs rising above the thorns to the south. A track would then appear, leading off towards them. And somewhere at the end of that track were villages of the Ju’/Hoansi Bushmen, who still lived almost entirely the traditional way, by hunting and gathering. We drove through Tsumkwe and out to the east, following these instructions. Sure enough, after twenty minutes or so, several great baobabs rose above the bush away to the right; vast, grey, building-sized trees topped with strangely foreshortened branches. The track appeared. We turned down it. The bush crowded in on either side of the vehicle, wild and lushly green from a season of good rain, swallowing us instantaneously.

We made camp under the largest of the great baobabs, an obese monster almost a hundred feet high, got a fire going and put some water on to boil. Looking around at the surrounding bush, which hereabouts was open woodland, we saw the grass standing tall and green in the little glades and clearings. Everything was in leaf, in flower. Fleshy blooms drifted down from the stunted branches of the baobab, making a faint plop as they landed on the sandy ground below. The blossoms had a strong scent, like over-ripe melon. And then there was a crunch of feet on dead leaves. We turned. Two Bushmen had walked into the clearing.

* (#ulink_e6fadff6-3bff-5159-b8a0-a53a65bed579) Village council.

* (#ulink_81776a8e-21cf-54e9-8fc9-eecb4de0b422) Traditional African round, thatched hut.

3 Under the Big Tree (#ulink_78b76841-f8db-5bb3-a571-c251df35a0fc)

In front walked a lean young man, wearing jeans and a torn white T-shirt, and whose sharp, finely drawn features made one think of a little hawk. Behind him came a shorter, grizzle-headed grandfather with a small, patchy goatee, dressed only in a skin loincloth. Above this curved a rounded belly – though not of fat. Rather it was as if the stomach, under its hard abdominal wall, had been stretched and trained to accommodate great feasts when times were good, as they seemed to be now, with the bush green and abundant with wild fruits. Both men had the golden, honey-coloured skin of full-blooded Bushmen. They stood facing us under the vast tree, silent, as if waiting for us to acknowledge their arrival. ‘Hi,’ I said. Kristin smiled.

Smiling shyly, the younger man stepped closer, into conversational range, and said in slow, perfect English: ‘I am Benjamin. And this is /Kaece [he pronounced it ‘Kashay’], the leader of Makuri village. You are welcome here.’

I had assumed that I would have to get by with signs and gesticulation, so it was startling to be addressed in my own language. Kristin and I got up, told the man Benjamin our names and offered him and /Kaece some coffee, which they accepted. Benjamin squatted down by our fire, while the older man took a seat on a buttress-like bit of baobab trunk, which jutted out from the main body of the tree like a small, solid table, and watched with frank, open curiosity, his eyes round like an owl’s.

‘Where did you learn English?’ I asked, trying to open a conversation, and hoping it wouldn’t sound rude, too direct.

‘Mission School,’ answered Benjamin, holding his coffee cup in both hands and sipping gently. ‘In Botswana,’ and he gestured to the east.

‘Perhaps you have some sugar?’ he added. ‘We like our coffee sweet.’ He smiled. Only when four spoonfuls had been deposited into each mug did he give a thumbs-up sign, turn to me again and repeat: ‘So, you are welcome.’

I looked at this young, articulate man with his perfect English and his good, if slightly frayed, clothes. I noticed that he was wearing Reeboks. ‘Are you from Makuri too?’ I said, gesturing back towards where he and the old man had come from.

‘No,’ said Benjamin. ‘I live at Baraka.’

‘Baraka?’

‘Yes. The field headquarters for the Nyae Nyae Farmer’s Co-operative.’ He pronounced the official-sounding words slowly, as if they did not sit easily on his tongue, using the monotone of one who must mentally translate the words before speaking. ‘Maybe twenty kilometres from here … I am a field officer, an interpreter.’

‘The Nyae Nyae what? What’s that?’ I asked, never having heard of it before.

‘An organisation, you know, an NGO, non-government organisation, aid and development.’ His voice was sleepy, hypnotic. ‘But it’s a problem there. Many problems. Sometimes these people say they want us to be farmers. Then another one comes and says no, we should be hunters. Too many foreign people always telling, telling, telling … They don’t ask us what we want.’ Benjamin’s tone became more vehement: ‘We the Ju’/Hoansi’; pronouncing the name ‘jun-kwasi’, with a loud wet click on the ‘k’.

‘The people round here,’ I ventured, ‘are they farmers then? Do they still hunt?’

‘Oh yes, they are hunting. There is a lot of game here – kudus, you know, wildebeests, gemsboks, everything …’ He took a sip of coffee. Dusk was falling and the birds had ceased their song. He was waiting for me to speak again.

‘Do you still have those skills? I mean, do you still hunt?’ I eyed his Western clothes apprehensively.

Benjamin smiled, inclined his head. ‘Yes, even me, I still have the skills.’

‘Tomorrow …’ I said, suddenly emboldened. ‘Would you take us hunting?’

Benjamin smiled again, a smile that seemed to say he knew that this question had been coming. Perhaps I wasn’t the first to ask. ‘Yes,’ he said. ‘Tomorrow at dawn we will come for you. We will walk far. Do you have water bottles?’

I looked over at Kristin, whose slim, black-eyed face, tanned dark beneath her freckles, was as excited as my own. ‘Yes,’ she said, ‘Yes, we’ll bring everything we need …’

Ten minutes later the two men had walked off into the dusk, the low murmur of their voices carried back to us on the breeze.

It was a hot night, full of flying insects. Small beetles, whirring into the firelight, committed suicide in our cooking pot. Occasionally, while eating our rice stew, we would crunch down on a hard-boiled wing-case. We didn’t care, so elated were we, but turned in early so as to be up before dawn, ready for the hunt. Hunting with the Bushmen. It was finally going to happen.

In the dim pre-dawn the bush came alive with the rustlings of small animals and strange chirruping sounds. The earth smelled greenly alive. It was just cool enough to raise a faint gooseflesh on the arms – a luxury when one thought of the heat to come. We made up the fire and brewed coffee, nursing our excitement, and listening to the chatter and whistle of the waking bush.

Imperceptibly, the blue darkness paled, and there came a lull in the birdsong. The pale light in the clearing blushed slowly from blue to rose, from rose to pink, with here and there a wisp of shining, gilded cloud, reflecting the still unrisen sun. Then, with sudden, astonishing speed, the sky became a vast roof of hammered gold and the sun itself came rising above the black boughs of the eastern bush.

But no one appeared in the clearing. We got the fire going again, made more coffee. Still no one came. Half an hour later, buzzing with the strong camp-brew, we could contain ourselves no longer, but picked up our day-packs, water bottles and cameras and went to find the nyore (village), which we knew lay a half-mile or so through the thick scrub.

We found Makuri village still sleeping. As we entered the circle of tiny, beehive huts, only the nyore’s pack of weaselly, starveling dogs were up to greet our arrival. They rushed towards us, barking. But despite the noise, no one appeared from the huts. We stood sheepishly in the centre of the village, throwing small stones at the dogs to keep them off. It was long past dawn now. The first heat was in the sun. Already some animals would be slinking into shady cover for the day. Were we too late? Had the hunters forgotten us and left already?

The rib-thin dogs began to fight among themselves – one had found a bloody section of tortoise-shell and the others wanted it. They chased and fought around the huts, yapping louder and louder until at last a flap in the low doorway of one of the little huts opened, and a wrinkled face appeared. Old man /Kaece crawled out, straightened stiffly, shouted at the animals to shut up and threw a tin mug at the nearest. He stretched luxuriously, raising his hands above his head, sticking out his hard belly and closing his eyes with the bliss of it. He yawned, then looked our way and, as if noticing us for the first time, nodded to us while energetically scratching his balls inside his xai and hawking up a great gob of phlegm. He spat it out, leant forward to examine the colour, and nodded, as if pleased with what he saw. Then, his morning ritual done, he shuffled over to the next-door hut and banged on the side.