По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

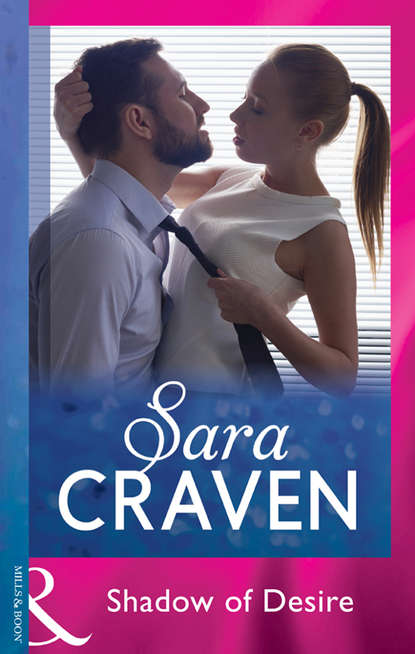

Shadow Of Desire

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘How do you do.’ She extended a hand which could have encompassed both Ginny’s slender ones. ‘My word, she saw you coming and no mistake! How’s a slip of a girl like you going to see to a great barn of a place like that?’

Ginny bit her lip. ‘I’m not afraid of hard work.’

‘You don’t need to be, working for her.’ Kathy got up from the desk where she was working with account books and ledgers. ‘I suppose you want to see round the place—see the worst, eh?’ She took a bunch of keys from a board by the door. ‘Mind you,’ she went on, leading the way through the stable yard round to the front of the house where Ginny had left the car, ‘it’s a wonder to me that her ladyship has taken you on at all—but I suppose she can’t afford to be choosy at the money she’s offering.’

‘Thank you.’ Ginny did not know whether to be amused or insulted at the older woman’s forthright remarks. ‘I assure you that I’m perfectly capable.’

Kathy shrugged. ‘Makes no matter to me, dearie, whether you are or not. As for her, you could be Mrs Beeton the second, and she still wouldn’t take you on. She likes her female staff to be battered old warhorses like me, not clear-skinned young girls—especially when there’s a man around.’

Ginny was startled. ‘You mean Mr Hendrick?’

Kathy gave an exaggerated sigh as she settled herself into the passenger seat. ‘None other. He’s all man, believe me. Madam there couldn’t wait for him to sign the lease.’

‘I see,’ Ginny said slowly, as she started the engine.

‘Well, I hope you do, ducky. No use in looking for trouble, is there? And she marked him down as hers the moment she laid eyes on him.’

Kathy might be appallingly indiscreet, but she seemed friendly enough, and Ginny laughed.

‘I’m not setting up in competition against her, believe me.’

‘You couldn’t, dearie.’ Kathy’s tone was dry. ‘You’d be left at the start. If she’d have thought there was the slightest danger you’d be looking for another job.’

As they drove down the narrow lane leading to Monk’s Dower, it occurred to Ginny that this was the first time her brown mouse looks had ever actually stood her in good stead, but this was not a particular comfort to her. A small flicker of rebellion stirred inside her at being so easily dismissed, but she stilled it. Her attractions, or lack of them, were the last thing that should be on her mind at this point in time.

Monk’s Dower was large and rambling, built on three sides of a courtyard in a variety of styles reflecting the periods when additions had been made. Her heart sank a little as she followed Kathy from room to room, because it was neither labour-saving nor convenient. There were open fires in the principal rooms, and wide expanses of ancient polished floorboards. Most of the furniture seemed old-fashioned without being antique, but there was a mellow air about the place which not even the slightly dank smell of disuse could dispel.

The kitchen was slightly more hopeful. It had been modernised and furnished with attractive pine units, and there was a modern wood-burning kitchen range as a centrepiece. The roomy walk-in pantry contained a large deep-freeze, Ginny noticed, and she supposed she would be expected to supply this with the kind of food a bachelor would need—whatever that was. Convenience food, she surmised vaguely, and chops and steaks.

‘The place smells damp.’ Kathy sniffed the air. ‘It wants living in—fires fighting. I told you it was a barn, didn’t I?’

‘Yes,’ Ginny acknowledged. ‘But it has character—and it could be lovely, if someone cared about it.’

Kathy’s lips twisted derisively. ‘The someone being you, I take it? Well, let me give you some good advice, ducky. Don’t knock yourself out—and don’t break your heart either. I’ve worked for her ladyship for years, but I’ve seen others come and go. Just do what you’re asked and take your money, but don’t make any special effort, because you won’t be thanked for it.’

Ginny tried to smile in reply, but Kathy’s cynicism disturbed her. She wondered how many years she had worked for Mrs Lanyon. Certainly she seemed to know her employer only too well.

She drove home feeling rather depressed when she should have been on top of the world, but when she arrived back at the house she was thankful that she had taken the job, because a social worker was waiting for her, being entertained rather stiffly by Aunt Mary who had been brought up to believe that Heaven helped those who helped themselves, and who disapproved of the Welfare State on principle.

The interview which followed was a rigorous one, because the children’s officer clearly did not believe that Ginny was old enough or responsible enough to be head of any sort of family. She listened with frank scepticism as Ginny outlined her plans and gave details of the new job.

‘You surely don’t expect to maintain yourself and a growing boy on a wage like that!’ was her immediate reaction.

‘Certainly not,’ said Ginny, who hadn’t even got around to considering the nuts and bolts of the situation. She cast round wildly in her mind for inspiration. ‘I—I’m going to be left with a lot of time on my hands, so I thought I’d—start a typing agency,’ she finished on a sudden gulp of relief, which she hoped had not been noticed by her inquisitor.

‘I see.’ The social worker looked frankly nonplussed, and after a few more rather desultory questions, took her leave, announcing brightly that she would ‘be in touch.’

‘I hope,’ Aunt Mary said reprovingly once they were alone, ‘that you haven’t deceived that unfortunate woman, Ginevra. Have you actually made enquiries into the need for such an agency?’

‘Well—no,’ Ginny said rather guiltily. ‘But I’m sure there are lots of people around who haven’t enough work for a full-time secretary. I shall advertise.’

‘Hm.’ Aunt Mary pursed her lips. ‘I hope your advertising is successful, my dear child. Our visitor’s remarks had a certain justice, you know. Tim is growing fast, and approaching the most expensive period in his life. It seems to me this post you’ve obtained is going to entail a great deal of work for very little return. Are you sure you’ve made the right decision?’

‘Part of the return is a roof over our heads,’ Ginny said gently. ‘That’s the most important thing.’

‘A roof, nevertheless, that’s dependent on the whim of others.’ Aunt Mary shook her head. ‘Not a comfortable situation, but we’ll have to hope for the best.’ She hesitated for a moment, then reached down for the capacious black leather handbag which accompanied her everywhere. ‘I’ve taken the precaution of writing away to a few places. You’re a good child, Ginevra, but I wouldn’t wish to inflict a greater burden on you than you’re able to bear.’

‘What do you mean?’ Ginny glanced at the sheaf of papers her great-aunt was extending to her. ‘The Sunny-view Home for the Aged,’ she read aloud in tones of disgust. ‘Oh, Aunt Mary, how could you! Your home is with us—you know it is.’

‘My home was with your dear parents,’ Aunt Mary corrected her, her back a little straighter than usual. ‘You’re very young, Ginevra, and you have every right to a life of your own.’ She paused. ‘I’m not by nature an eavesdropper, but I happened to come downstairs one night while your sister was here. I couldn’t avoid overhearing what she was saying, she produces her voice extraordinarily well—part of her stage training, I suppose.’

‘Aunt Mary!’ Ginny was aghast. ‘You—you really mustn’t take any notice of Barbara. We see things from completely different angles and …’

‘I’m aware of that,’ Aunt Mary said rather acidly. ‘If you shared her viewpoint, this conversation would probably not be taking place. But she was not entirely in the wrong, although I found her mode of expression rather hurtful. Are you quite sure that Tim is not more than sufficient responsibility for you?’

‘Quite sure.’ Ginny’s voice was firm. ‘Aunt Mary, you can’t let me down. I—I need you. No matter what I told that woman, I’m going to have my work cut out looking after that house. If you could help with the cooking and—just be there when Tim gets in from school,’ she ended on a note of appeal.

‘I shall be pleased to do whatever I can.’ Aunt Mary allowed her firm lips to relax into a smile. ‘And I’m not entirely decrepit, Ginevra. I daresay I could make beds and help with the dusting, as well.’

Impulsively Ginny put her arms round her great-aunt and hugged her. Aunt Mary did not, as a rule, welcome random demonstrations of affection, but this time when Ginny released her, she looked pink and pleased, even though she said robustly, ‘Go along with you, child.’

In the intervening two months, Ginny thought, things had worked out better than she had ever dared hope. The move to Monk’s Dower had gone quite smoothly, and Tim was now settled at his new school, with only the occasional nightmare reminding him of the tragic disruption his young life had suffered.

The job itself was proving rather easier than she had expected. Mrs Petty who came in from the village on an ancient bicycle twice a week turned out to be slipshod but willing, but fortunately, Ginny thought with satisfaction, her new employer was not the type of man to go peering in corners after a few stray cobwebs.

The colour deepened in her face as she thought about Toby Hendrick. He was altogether different from what she had expected. For one thing, he was much younger, and far better looking, with fair hair and smiling blue eyes.

He had arrived at Monk’s Dower without giving her any preliminary notice, and the first inkling she had had that the main part of the house was occupied was the gleaming monster of a car parked in the courtyard. She had gone across immediately, her heart sinking. This was her first test as a housekeeper and she’d failed it pretty comprehensively, she thought savagely as she let herself in. His bed wasn’t made up, for one thing, and there was no bread or milk in his part of the house, although they had plenty and could share with him.

She was quaking when she arrived in the kitchen and found him on his knees, trying, with a lot of muffled cursing, to get the range going. Ginny had taken over from him, stammering her apologies, but he’d waved them laughingly aside.

‘I didn’t know I was coming down myself until a few hours ago, I’m a creature of impulse, I’m afraid, Miss—–?’

‘Clayton,’ she supplied. ‘Ginny Clayton.’

‘Toby Hendrick.’ He shook hands solemnly with her. ‘As we’re going to be seeing a lot of each other, shall we cut the formality? I’d much rather call you Ginny.’

She said, ‘That’s fine with me,’ letting a curtain of hair fall forward across her face to mask her embarrassment.

No, Toby had certainly not been what she expected. Kathy’s descriptive phrase ‘all man’ had prepared her for someone rather different, although she was at a loss to know what. She was glad that the shadowy and rather formidable figure she had built up in her mind was only a figment of her imagination. He certainly wouldn’t have been as easy to work for as Toby, she thought, smiling to herself.

And Kathy had been wrong about Vivien Lanyon’s interest in him too. She had rung up a couple of times while Ginny was working in the house to make sure that everything was all right, but the exchanges between Toby and herself had been brief and formal in the extreme. Nor had she been over to Monk’s Dower, and Ginny told herself that if Mrs Lanyon had been really interested in Toby, she would never have been away from the door. Perhaps she had decided it was rather degrading to chase a young man who was patently her junior, Ginny thought.

After his first visit, which had lasted only two days, Toby had vanished for three weeks. Then one evening he had telephoned to warn that he would be coming for the weekend, and this time Ginny was fully prepared.

His room was ready, with fresh towels laid out in the adjoining bathroom, and a bowl of early daffodils set on the dressing table. The drawing room fire was lit, and the kitchen range was glowing, while the appetising aroma from a beef stew cooking in its oven crept through the house.

Cooking for Toby did not come within Ginny’s official list of duties, but she told herself rather defensively that as she was preparing the stew anyway, it took little effort to put some of the ingredients into a separate casserole. Aunt Mary had raised a caustic eyebrow as she had haltingly tried to explain this, but made no comment.