По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

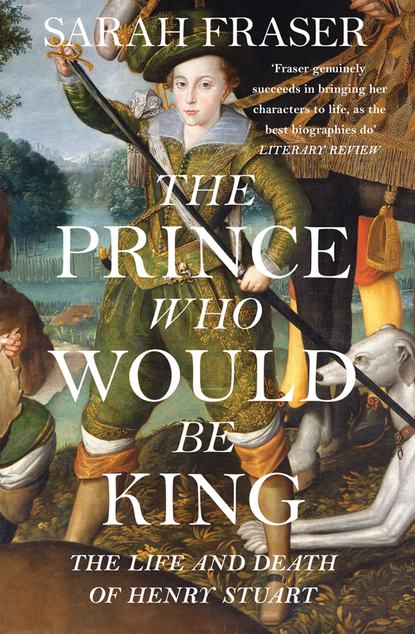

The Prince Who Would Be King: The Life and Death of Henry Stuart

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

19 Henry’s Foreign Policy: ‘Talk for peace, prepare for war’ (#litres_trial_promo)

20 Heir of Virginia: ‘There is a world elsewhere’ (#litres_trial_promo)

PART THREE: PRINCE OF WALES, 1610–12 (#litres_trial_promo)

21 Epiphany: ‘To fight their Saviour’s battles’ (#litres_trial_promo)

22 Prince of Wales: ‘Every man rejoicing and praising God’ (#litres_trial_promo)

23 Henry’s Men Go to War: Jülich-Cleves (#litres_trial_promo)

24 Henry Plays the King’s Part: King of the Underworld (#litres_trial_promo)

25 From Courtly College to Royal Court (#litres_trial_promo)

26 Court Cormorants: Henry and the king’s coterie (#litres_trial_promo)

27 The Humour of Henry’s Court: Coryate’s Crudities (#litres_trial_promo)

28 Marital Diplomacy: ‘Two religions should never lie in his bed’ (#litres_trial_promo)

29 Supreme Protector: The Northwest Passage Company (#litres_trial_promo)

30 Selling Henry to the Highest Bidder: ‘The god of money has stolen Love’s ensigns’ (#litres_trial_promo)

31 A Model Army: ‘His fame shall strike the Starres’ (#litres_trial_promo)

32 End of an Era: ‘My audit is made’ (#litres_trial_promo)

33 Wedding Parties: ‘Let British strength be added to the German’ (#litres_trial_promo)

34 Henry Loses Time: ‘I would say somewhat, but I cannot utter it!’ (#litres_trial_promo)

35 Unravelling: After 6 November 1612 (#litres_trial_promo)

36 Endgame (#litres_trial_promo)

Notes (#litres_trial_promo)

Bibliography (#litres_trial_promo)

Acknowledgements (#litres_trial_promo)

Picture Section (#litres_trial_promo)

Illustration Credits (#litres_trial_promo)

Index (#litres_trial_promo)

By the Same Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Author (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

(#ub3b57da1-b2da-52aa-9601-7e702768554d)

(#ub3b57da1-b2da-52aa-9601-7e702768554d)

CONVENTIONS AND STYLE (#ub3b57da1-b2da-52aa-9601-7e702768554d)

Spelling and punctuation, unstable in this period, are modernised to assist comprehension, and to prevent interruption of the narrative by lexical curiosities that might catch the eye and distract from the narrative flow. Even James VI and I revised his Basilikon Doron for publication to ease readability.

Contractions are expanded (thus mistie becomes Majesty). The spelling of proper names has been standardised. For example, Henry also spelled his name ‘Henrie’, but I have opted here for Henry. Individuals born with several titles, or those who changed name on receipt of them, can be a particular problem for the biographer writing for a non-specialist audience. Cecil was not the monolith ‘Salisbury’ when James VI negotiated in treasonable secrecy with Secretary Robert Cecil to inherit Elizabeth’s thrones. I note in media res when an important change has taken place and from then on, I use the new name. With regard to place names, ‘Great Britain’ as a term for the multiple Stuart territories is a bit of an anachronism, but I use it as it is so apposite. Place names are modernised and standardised (thus Finchingbrooke becomes Hinchingbrooke).

For dates, the year begins on 1 January not 25 March (as it did on this side of the Channel).

British currency was in pounds, shillings and pence: £s. d. One English pound was worth £12 Scots. To understand what a particular amount would represent today you can add two zeros to the figure, to get a rough approximation.

PREFACE

Effigy (#ub3b57da1-b2da-52aa-9601-7e702768554d)

‘How much music you can still make with what remains’

– ITZHAK PERLMAN

In the conservation room at Westminster Abbey lies the wreck of a life-sized wooden manikin, stretched out on a white table. This is what remains of Henry Frederick Stuart, Prince of Wales.

Recalling a cast of the nameless dead at Pompeii, the figure’s mute appeal touched me. Its ruined state tells of Henry’s importance, but also what happened to his legacy. After Henry died, visitors ransacked this likeness for relics – someone even stole his head. His effigy was unique in 1612. Up until then, they were made to honour monarchs and their consorts, not their offspring.

Who was Henry Stuart, to earn this effigy, and the state funeral that went with it – itself unprecedented in England, in scale and magnificence?

This book sets out to recreate Henry, an important but almost forgotten piece of history’s puzzle. Restoring Henry in his time and place reveals paths running through his court, from Elizabeth I to the Civil War, to a Puritan republic, and the British Empire in America; but also, to the transformation of the navy into a force achieving global domination of the high seas, and the breaking down and recreation of Britain’s armed forces into a world-class fighting machine.

Henry re-founded the Royal Library, amassing the biggest private collection in England. He began to create a royal art collection of European breadth – paintings, coins, jewellery and gem stones, sculpture, both new and antique, on a scale no royal had attempted before. These went on to become world-class collections under his brother, Charles I, and form the backbone of the British Library and the Queen’s Royal Collection today. Henry began the grandest renovations of royal palaces in his father King James VI and I’s reign, and mounted operatic, highly politicised masques. His court maintained a dozen artists, musicians, writers and composers. Ben Jonson, Michael Drayton, George Chapman and Inigo Jones all created work for him. He responded with enthusiasm to the vogue for scientific research, putting time, money and men into buying state-of-the-art scientific instruments – telescopes and automata that tried to model the heavens. He financed ‘projects’ – business schemes – to try and extract silver from lead, and make furnaces more fuel efficient.

Henry and his circle’s curiosity and ambition reflected the era’s desire to sail through the barriers of the known world. He persuaded his father the king to let him begin a full-scale review and modernisation of Britain’s naval and military capacity. He was raised in the ancient culture of chivalry, but welcomed active servicemen from the front line of Europe’s religious wars. Henry’s court was where the latest developments in the art of warfare were received and developed. He became patron of the Northwest Passage Company, established to find a sea route across the top of America and open up the lucrative oriental trade to British merchants. He and his court were important promoters of the project to realise the decades-long dream of planting the British race permanently in American soil. Whatever we think of colonialisation now, such men transformed the world.

As a man and prince, Henry saw himself to be European as much as British, using as one of his mottoes the expansionist ‘Fas est aliorum quaerere regna’, ‘It is right to ask for the kingdoms of others’. At his death aged eighteen, he was preparing to go and stake his claim to be the next leader of Protestant Christendom in the struggle to resist a resurgent militant Catholicism. He was a devout, Puritan-minded Protestant. In the arena of politics, there is a case for seeing Henry’s court as a significant waystation between the abortive aristocratic uprising in 1601 – when the 2nd Earl of Essex sought to force Queen Elizabeth to name James VI of Scotland as her heir in Parliament – and the regicides who shivered in the Palace of Westminster’s Painted Chamber, ready to sign the death warrant of Henry’s little brother, Charles I, in January 1649. By the time of Henry’s death, you could see the prince and his court positioning themselves at the front line of so much that came to define Britain in its heyday.

I am aware that when I say, Henry did this, and Henry did that, one question arises at once. Who was Henry?

Henry was a son, brother, friend, master, patron. ‘Henry’ was the crown prince. The inverted commas around his name allude to the medieval idea of the king’s two bodies – ordinary man and the monarchy, the Crown. The natural man decayed and died. The Crown merely suffered a demise and passed to the next bearer. Crown Prince Henry possessed a physical body and a body politic. He was a boy and the crowns united: the first Prince of Wales born to inherit the united kingdoms of Britain.

His legacy stretched beyond his death to the conflagration coming in 1618. The Thirty Years’ War would be the longest, bloodiest conflict in European history until the First World War in 1914. It tore Europe apart, and Henry had been determined to drag England towards involvement in it. What did that imply about his character?

He was only nine when he came to England. For nearly a decade in Scotland and nearly a decade in England some of the most influential men, and women, of the Jacobean age wanted to shape the character of the future king and his monarchy. Who he responded to, and to whom he did not, suggests what kind of king he would have made.