По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

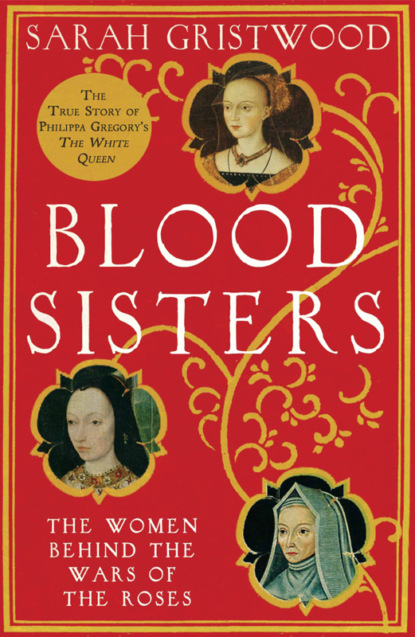

Blood Sisters: The Hidden Lives of the Women Behind the Wars of the Roses

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Contemporary commentators never spoke of the ‘Wars of the Roses’.

The name itself is a much later invention, variously credited to the historian David Hume in the eighteenth century and the novelist Sir Walter Scott in the nineteenth. The idea of the two roses was in currency not long after the event, and the white rose was indeed a popular symbol for the house of York, one party in the conflict, but the red rose was never widely identified with their opponents, the house of Lancaster, until the moment when Henry VII, poised to take over the country in 1485, sought an appropriate and appealing symbol – soon merged, in the first days of his kingship and after his marriage to Elizabeth of York, into the red and white unifying ‘Tudor rose’.

In some ways, moreover, the attractive iconography of the two roses does history a disservice, implying a neat, two-party, York/Lancaster divide. In reality the in-fighting which tore the ruling class of England apart for more than three decades was never just a dispute between two families, as clearly separate as the Montagues and the Capulets. The ‘Wars of the Roses’ are more accurately called the ‘Cousins’ War’, since all the protagonists were bound together by an infinite number of ties. And these conflicts should really be seen in terms of politics – secret alliances, queasy coalitions, public spin and private qualms. It was a world in which positions were constantly shifted and alliances changed from day to day.

In 1445, the last undisputed king of England had died almost seventy years before. He had been the powerful and prolific Edward III, latest in the long line of Plantagenet kings who had ruled England since the Norman Conquest. But in 1377 Edward was succeeded by his grandson (the son of his dead eldest son), the ten-year-old Richard II. Richard was deposed in 1399 by his cousin, Shakespeare’s Bolingbroke, who became Henry IV and was succeeded by his son Henry V, who in turn was succeeded by his son Henry VI. So by 1445 this Lancastrian line had successfully held the throne for almost half a century.

There had, however, been an alternative line of succession in the shape of the Yorkists – descended, like the Lancastrians, from Edward III’s younger sons. The white rose Yorkists had arguably a better claim than the Lancastrians, depending on the attitude taken to a woman’s ability to transmit rights to the throne: while the Lancastrian progenitor, John of Gaunt, had been only Edward’s third son, the Yorkists were descended in the female line from his second son Lionel, as well as in the male line from his fourth son, Edmund. And there was no denying the fact that, because Henry V had died so early and Henry VI had therefore succeeded as a nine-month-old baby, men had begun to cast their eyes around and think of their opportunities. There was no denying, either, that even now Henry seemed both reluctant and unfitted to assume his destined role. If Henry – now mature, now married – were indeed to prove himself a strong king, the Lancastrian line should hold the throne indefinitely. If not, however, there was that other possibility: the more so since the present Duke of York, while still loyal to the crown, was an able and active man (an ally of Humfrey Duke of Gloucester) and married to a woman – Cecily Neville – as forceful as himself.

In 1445, the year Marguerite of Anjou arrived in England, neither Anne Neville nor Margaret of Burgundy had yet been born, let alone Elizabeth of York. Elizabeth Woodville – about eight years old, though no one had bothered to record her precise date of birth – was growing up in rural obscurity. Indeed, out of our seven protagonists only Cecily Neville was a woman of full maturity. Margaret Beaufort was just a toddler, though her bloodline meant she was already a significant figure, a prize for whom others would compete. While Cecily would become the matriarch of the ruling house of York, Margaret’s bloodline was an important carrier of the Lancastrian claim. In fact, at this moment she (or any son she might bear) might be considered heir presumptive to the throne until children came to her kinsman Henry VI.

Margaret Beaufort had been born in 1443 at Bletsoe in Bedfordshire. Her mother was a comparatively obscure widow who already had children by her first husband, Sir Oliver St John. Margaret’s father, however, was the Earl (later Duke) of Somerset, and from him she inherited a debatable but intriguing relationship to the throne.

Her grandfather, the first Earl of Somerset, had been one of John of Gaunt’s sons by his mistress Katherine Swynford. John’s nephew, Richard II, had confirmed by binding statute that all the children of the pair were rendered legitimate by their subsequent marriage, and able to inherit dignities and estates ‘as fully, freely, and lawfully as if you were born in lawful wedlock’. When John of Gaunt’s eldest son (by Blanche of Lancaster) seized Richard’s throne, and had himself declared Henry IV, this first Earl of Somerset became half-brother to the king. But when in 1407 Somerset requested a clarification of the position laid down in that earlier legitimation, the resultant Letters Patent confirmed his entitlement to estates and noble rank with one very crucial proviso – ‘excepta dignitate regali’, excepting the dignities of the crown.

Less controversially, Margaret was also heiress to great lands. But by the time of her birth, the anomalies of her family’s position – royal, but yet possibly excluded from ruling – had been compounded by her father’s chequered career.

Somerset had been captured as a young man in the wars with France, and held captive there for seventeen years. When he returned to England only a few years before Margaret’s birth, he set about trying to assume the position to which he felt his blood entitled him – but, as the author of the Crowland Abbey chronicles put it, ‘his horn was exalted too greatly on high’.

In 1443 his position – his closeness in blood to a king short of relatives – had led to his appointment as commander of England’s army in fresh hostilities against the French. But the campaign was a disaster and Somerset was summoned home in disgrace, his daughter having been born while he was away. Only a few months later, in May 1444, he died, the Crowland chronicler asserting (‘it is generally said’) that he had committed suicide – a heinous sin in the fifteenth century. The rumours surrounding his death only added to the dubiousness of the baby Margaret’s position, and perhaps later increased her well-documented insecurities.

Somerset’s brother Edmund, who succeeded to the title, was able to ensure that the Beaufort family retained their influence – not least because of the friendship he would strike up with the new queen. It was this friendship which would bring him into conflict with the Duke of York, and with York’s wife Cecily.

Born in 1415 to the powerful Ralph Neville, Earl of Westmorland, and known as the beautiful ‘Rose of Raby’ after the family stronghold, Cecily was the daughter of his second marriage, to Joan Beaufort – of the same notably Lancastrian family as Margaret Beaufort. But the political divisions of later years had not yet taken shape and indeed, though Cecily would become the Yorkist matriarch, her father had supported the Lancastrian usurpation of Richard II by John of Gaunt’s son, Henry IV.

Joan Beaufort was John of Gaunt’s daughter by Katherine Swynford – in later years Cecily, John of Gaunt’s granddaughter, might have found it galling that Margaret Beaufort could be regarded as inheriting John of Gaunt’s Lancastrian claim when she was only his great-granddaughter. The vital difference was that Margaret’s claim had come through her father and her father’s father – through the male line.

By the time Cecily was born in May 1415, the Neville family was enormous. Joan Beaufort had two daughters from her first marriage, and when she married Ralph he had a large family already. They went on to produce ten more surviving children. By contrast Cecily’s husband, Richard of York, had just one sister. His marriage would bring him an almost unparalleled number of in-laws, but in the fifteenth century in-laws figured as potentially trustworthy allies and were more a blessing than a curse. Certainly the Nevilles would – in many ways, and for many years – do Richard proud.

Richard had been born in 1411, grandson to Edward III’s fourth son, Edmund. In 1415 his father (another Richard) was executed for his involvement in a plot against Henry V. The child eventually became Ralph Neville’s ward. By that time the boy had inherited the dukedom of York from a childless uncle; and later another childless uncle died, this time on his mother’s side, leaving Richard heir to the great Welsh and Irish lands of the Mortimer family.

Whether or not there were any thought that he might be king-in-waiting, York was an undoubted catch and it was inevitable that Ralph Neville would hope to keep this rich matrimonial prize within his own family. York’s betrothal to Cecily took place just a year after he came into the Nevilles’ care. The following year Ralph himself died, and York’s wardship passed into the hands of Cecily’s mother, Joan. Full, consummated marriage would have been legal when Cecily was twelve, in 1427, and had certainly taken place by 1429 when permission was received from the papacy for them jointly to choose a confessor.

In medieval terms, Cecily was lucky. She would have known Richard well and he was only four years her elder. And since Richard, like Joan, had moved into the glittering world of the court, it seems probable that Cecily would have done so, too – unless separations are to be deduced from the fact that their first child was not born for several years, though after that they came with notable frequency.

Cecily gave birth to that first child – a daughter, Anne – in 1439 and a first son, Henry, in February 1441 at Hatfield: then the property of the Bishop of Ely, but frequently available to distingushed visitors or tenants. But Henry did not live long; just as well, perhaps, that Cecily had the distraction of an imminent move to France, where York had been appointed governor of the English territories, still haunted by the spectre of Joan of Arc, the holy Maid, burnt there only a decade before. In Rouen, the capital of English Normandy, the couple set up home in such state that an officer of the household had to be appointed to overlook Cecily’s expenditure,

which included lavishly jewelled dresses and even a cushioned privy. Their second son, the future Edward IV, was born there in April 1442; another son, Edmund, in May 1443; and a second daughter, Elizabeth, the following year.

There is no evidence from that time of rumours concerning Edward’s paternity. But in the years ahead there would be debate about the precise significance of his date of birth

and where Richard of York had been nine months before it; about the hasty and modest ceremony at which he was christened; and about his adult appearance and physique, which were singularly different from Richard’s. It is true that Edward was christened in a private chapel in Rouen Castle, while his younger brother Edmund was christened in the far more public arena of Rouen Cathedral – but that may have meant no more than that Edward seemed sickly; all the likelier, of course, if he were premature. It is also true that Edward, the ‘Rose of Rouen’, was as tall and physically impressive as his grandson, Henry VIII, while Richard of York was dark and probably small. But perhaps Edward simply took after his mother, several of whose other children would be tall too.

York himself showed no sign of querying his son’s paternity;

while the fact that he and the English government held lengthy negotiations concerning a match between Edward and a daughter of the French king hardly suggests suspicion about his status. This was not, moreover, the first time an allegation of bastardy had been levelled at a royal son born abroad – John of Gaunt, born in Ghent, had been called a changeling. In the years ahead Cecily’s relationship with her husband would give every sign of being close and strong. And then there is the question of the identity of her supposed lover – an archer called Blaybourne. For a woman as status-conscious as Cecily – the woman who would be called ‘proud Cis’ – that seems especially unlikely. There are certainly queries as to how the story spread. The Italian Dominic Mancini,

visiting England years later at a time when it had once again become a matter of hot debate, said that Cecily herself started the rumour when angered by Edward. A continental chronicler has it relayed by Cecily’s son-in-law Charles of Burgundy.

But sheer political expedience apart, time and time again it will be seen how slurs could be cast on women (four out of the seven central to this book) through claims of sexual immorality.

Certainly Cecily was still queening it in Rouen as Duchess of York when, in the spring of 1445, the young Marguerite of Anjou passed through the city on her way to England and marriage with Henry VI. It may have been here that the thirty-year-old woman and the fifteen-year-old girl struck up a measure of friendship that would survive their husbands’ future differences – one example among many of women’s alliances across the York/Lancaster divide. But at this point Marguerite’s role was far the grander, even if beset with difficulty.

THREE

A Woman’s Fear

If it be fond, call it a woman’s fear;

Which fear, if better reasons can supplant,

I will subscribe, and say I wronged the duke.

Henry VI Part 2, 3.1

When Marguerite arrived in England, her recent acquaintance Cecily was not far behind her. In that autumn of 1445, her husband’s posting in France came to an end; Richard and Cecily returned home and settled down. In May 1446 another daughter, Margaret (the future Margaret of Burgundy), was born to them, probably at Fotheringhay in Northamptonshire, while the two eldest boys were likely to have been given their own establishment, at Ludlow – a normal practice among the aristocracy. But the couple were now embittered and less wealthy, since the English government had never properly covered their expenses in Normandy.

York had hoped to have been appointed for another spell of office but was baulked, not least by Beaufort agency – the cardinal and his nephew Somerset. It was this, one chronicler records, that first sparked the feud between York and the Beauforts, despite the fact that the latter were Cecily’s mother’s family. The Burgundian chronicler Jean de Waurin

says also that Somerset ‘was well-liked by the Queen. … She worked on King Henry, on the advice and support of Somerset and other lords and barons of his following, so that the Duke of York was recalled to England. There he was totally stripped of his authority. …’ York now had a long list of grievances, dating back a decade to the time when a sixteen-year-old Henry VI had begun his own rule without giving York any position of great responsibility.

If York belonged to the ‘hawks’ among the country’s nobility, so too did the king’s uncle, Humfrey of Gloucester. By the autumn of 1446 King Charles was demanding the return of ever more English holdings in France, and Henry VI, under Marguerite’s influence, was inclined to grant it. But Humfrey, who would be a powerful opponent of this policy, would have to be got out of the way. In February 1447 – under, it was said, the aegis of Marguerite, Suffolk and the Beaufort faction – Gloucester was summoned to a parliament at Bury St Edmunds, only to find himself arrested by the queen’s steward and accused of having spread the canard that Suffolk was Marguerite’s lover. He was allowed to retire to his lodgings while the king debated his fate but there, twelve days later, he died. The cause of his death has never been established and, though it may well have been natural, inevitably rumours of murder crept in – rumours, even, that Duke Humfrey, like Edward II before him, had been killed by being ‘thrust into the bowel with an hot burning spit’.

Gloucester had been King Henry’s nearest male relative and therefore, despite his age, heir. His death promoted York to that prominent, tantalising position. The following month Cardinal Beaufort died too. The way was opening up for younger men – and women. Marguerite did not miss her opportunity and over the next few years could be seen extending her influence through her new English homeland, often in a specifically female way.

A letter from Margery Paston, of the Norfolk family whose communications tell us much about the events of these times, tells of how when the queen was at Norwich she sent for one Elizabeth Clere, ‘and when she came into the Queen’s presence, the Queen made right much of her, and desired her to have a husband’. Marguerite the matchmaker was also active for one Thomas Burneby, ‘sewer for our mouth [food taster]’, telling the object of his attention that Burneby loved her ‘for the womanly and virtuous governance that ye be renowned of’. To the father of another reluctant bride, sought by a yeoman of the crown, she wrote that, since his daughter was in his ‘rule and governance’, he should give his ‘good consent, benevolence and friendship to induce and excite your daughter to accept my said lord’s servant and ours, to her husband’. Other letters of hers request that her shoemaker might be spared jury service ‘at such times as we shall have need of his craft, and send for him’; that the game in a park where she intended to hunt ‘be spared, kept and cherished for the same intent, without suffering any other person there to hunt’. For a queen to exercise patronage and protection – to be a ‘good lady’ to her dependants – was wholly acceptable. But Marguerite was still failing in her more pressing royal duty.

In contrast to that of the prolific Yorks, the royal marriage, despite the queen’s visits to Thomas à Becket’s shrine at Canterbury, was bedevilled by the lack of children. A prayer roll of Marguerite’s, unusually dedicated to the Virgin Mary rather than to the Saviour, shows her kneeling hopefully at the Virgin’s feet, probably praying for a pregnancy. One writer had expressed, on Marguerite’s arrival in England, the Psalmist’s hope that ‘Thy wife shall be as the fruitful vine upon the walls of thy house’; and the perceived link between a fertile monarchy and a fertile land only added to the weight of responsibility. As early as 1448 a farm labourer was arrested for declaring that ‘Our Queen was none able to be Queen of England … for because that she beareth no child, and because that we have no prince in this land.’

The problem was probably with Henry, whose sexual drive was not high. The young man who famously left the room when one of his courtiers brought bare-bosomed dancing girls to entertain him may also have been swayed by a spiritual counsellor who preached the virtues of celibacy. But it was usually the woman who was blamed in such circumstances, and so it was now. A child would have aligned the queen more clearly with English interests, and perhaps removed from her the pressure of making herself felt in other, less acceptable, ways. Letters written by the king were now going out accompanied by a matching letter from the queen, and it was clear who was the more forceful personality.

Henry VI had never managed to implement his agreement to return Anjou and Maine to France, and in 1448 a French army had been despatched to take what had been promised. The following year a temporary truce was broken by a misguided piece of militarism on the part of Somerset, now (like his brother before him) England’s military commander in France and (like his brother before him) making a woeful showing in the role. The French retaliation swept into Normandy. Rouen – where York and Cecily had ruled – swiftly fell, and soon Henry V’s great conquests were but a distant memory. York would have been more than human had he not instanced this as one more example of his rival’s inadequacies, while Suffolk (now elevated to a dukedom) did not hesitate to suggest that York aspired to the throne itself. In 1449 York was sent to occupy a new post as governor of Ireland – or, as Jean de Waurin had it, ‘was expelled from court and exiled to Ireland’. Cecily went with him and there gave birth to a son, George, in Dublin. The place was known even then as a graveyard of reputations; still, given the timing, they may have been better off there in comfortable exile. English politics were becoming ever more factionalised, and some of the quarrels could be seen swirling around the head of Margaret Beaufort, only six years old though she might have been.

After her father’s death wardship of the valuable young heiress, with the right to reap the income of her lands, had been given to Suffolk – although, unusually for the English nobility, the baby was at least left in her mother’s care. Her marriage, however, was never going to be left to her mother to arrange. By 1450 she was a pawn of which her guardian had urgent necessity.

Most of the blame for the recent disasters in England’s long war with France had been heaped on Suffolk’s head (though there was enmity left over and to spare for Marguerite, whose father

had actually been one of the commanders in the French attack). Suffolk was arrested in January 1450; immediately, to protect the position of his own family, he arranged the marriage of the six-year-old heiress Margaret to his eight-year-old son John de la Pole. Presumably in this, as in everything else, Suffolk had Queen Marguerite’s support.

The marriage of two minors, too young to give consent, and obviously unconsummated, could not be wholly binding: Margaret herself would always disregard it, speaking of her next husband as her first. None the less, it was significant enough to play its part; when, a few weeks later, the Commons accused Suffolk of corruption and incompetence, and of selling out England to the French, prominent among the charges was that he had arranged the marriage ‘presuming and pretending her [Margaret] to be next inheritable to the Crown’.

Suffolk was placed in the Tower, but appealed directly to the king. Henry, to the fury of both the Commons and the Lords, absolved him of all capital charges and sentenced him to a comparatively lenient five years’ banishment. Shakespeare has Marguerite pleading against even this punishment,

with enough passion to cause her husband concern and to have the Earl of Warwick declare it a slander to her royal dignity. But in fact the king had already gone as far as he felt able in resisting the pressure from both peers and parliament, who would rather have seen Suffolk executed. And indeed, when at the end of April the duke finally set sail, having been granted a six-week respite to set his affairs in order, their wish was granted. Suffolk was murdered on his way into exile, his body cast ashore at Dover on 2 May.

It had been proved all too clearly that Henry VI, unlike his immediate forbears, was a king unable to control his own subjects. Similarly, Marguerite had none of the power which, a century before, had enabled Isabella of France to rule with and protect for so long her favourite and lover Mortimer. It has been said that when the news of Suffolk’s end reached the queen – broken to her by his widow, Alice Chaucer – she shut herself into her rooms at Westminster to weep for three days. In fact, king and queen were then at Leicester, which casts some doubt on the whole story – but tales of Marguerite’s excessive, compromising grief would have been met with angry credence by the ordinary people.

It was said at the time that, because Suffolk had apparently been murdered by sailors out of Kent, the king and queen planned to raze that whole county. Within weeks of his death came the populist rising led by Jack Cade, or ‘John Amend-All’ as he called himself, a colourful Yorkist sympathiser backed by three thousand mostly Kentish men. The rebels demanded an inquiry into Duke Humfrey’s death, and that the crown lands and common freedoms given away on Suffolk’s advice should all be restored. They also made particular complaint against the Duchess of Suffolk; indeed, her perceived influence may have been the reason that, the following year, parliament demanded the dismissal of the duchess from court.