По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

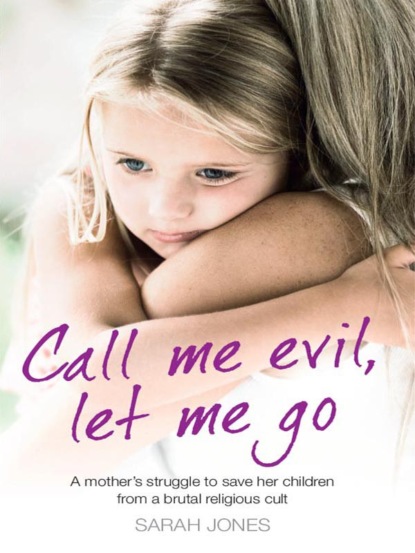

Call Me Evil, Let Me Go: A mother’s struggle to save her children from a brutal religious cult

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

There were some difficult and disruptive children at the school and I knew Mum and Dad were worried about their influence on me. They were right, but the small voice inside me was always aware of what was right and wrong. It was just that at the time it was outweighed by my longing for fun. I started lying to them. I’d say I was staying overnight with a friend and instead went with a gang of about four or five to the woods and stayed up all night drinking and smoking. At about 6 a.m. the next morning we’d all return home bleary-eyed, smelling of fags and cider.

One day as we lay in a clearing in the woods, we made a pact to steal trinkets from the gift shop in the village. It was a ridiculous and horribly dishonest thing to do, not least because the community was very small and everyone knew everyone else. I wanted to back out, but as none of us dared make the first move, I went along too and we all lifted some jewellery. Not surprisingly, a day later a policeman turned up at my home and demanded I hand back what I had taken. I went to my bedroom where I had hidden it all but cheekily decided to give him only half of my haul. Two days later he returned and asked for the rest. This time I handed everything over. My parents were mortified and I was lucky the shop didn’t press charges. Instead, Dad took me down to the police station and made me stand in front of the local senior officer, who gave me a severe talking-to. I was very submissive, felt thoroughly ashamed and said I would never do it again.

Even at the time I could tell that my bad behaviour was a reaction to both what had happened at home with Roy and mixing with the wrong crowd. I felt awful about letting Dad down, as he was such a loving father and worked so hard for us. Because of all of this I never shoplifted again. Instead I started playing truant, which I am not proud of either. Mum didn’t notice anything when I went out in the morning at the right time in my school uniform but with a pair of jeans or a long skirt stuffed into my satchel. Once I was out of sight I changed direction and met some friends who were also skipping school and we would go off for the day. I even had the cheek to phone the school secretary and, pretending to be my mother, said I had a bad cold and managed to stay away for a week.

Eventually Mum noticed that my school uniform wasn’t getting dirty and that I never had any homework. When she challenged me I admitted I had been skipping school. She was so worried about me that she gave up her part-time secretarial job so she could be at home to keep an eye on me. The problem was, I didn’t have either the incentive or the discipline to work, as I felt I could never perform as well as my high-achieving sister.

Around this time I started having boyfriends and pretty soon I lost my virginity. I even tried sniffing glue. With a group of friends I went to our woodland haunt where I poured some Tippex correction fluid into a plastic bag and breathed in the fumes. Fortunately, I quickly realized it was a very dangerous thing to do and stopped immediately, although I experienced a brief ‘high’ followed by a crashing headache. I never tried it again nor touched any other drug, despite my attempt to look and behave like a hippie.

I further disgraced myself when I was invited to a birthday party in a local hall by one of the sixth-form girls at school. I was much younger than nearly everyone else there and when the other guests started dancing I went round sipping their alcoholic drinks. It was a mad thing to do and I ended up being terribly sick in the ladies’ loo. My timing was terrible because there was a police raid just as I was throwing up. They were obviously looking for drugs and under-age drinkers, and when they found me in the toilets they rang my father. He came to pick me up but refused to say one word to me during the half-hour drive home. He didn’t have to. His look of disapproval was enough. Once we were home he said curtly, ‘I will speak to you in the morning, young lady.’ I went to bed feeling ill and stupid. Next morning Dad gave me a thorough telling-off. I knew my behaviour had been wrong and I felt ashamed that I had embarrassed my parents.

Mum and Dad remained very worried about me, and although it was obvious that I was not mentally ill, after all they had gone through with Roy they couldn’t face another spell of adolescent bad behaviour and the resulting tension at home.

Meanwhile Black’s Society of Christ’s Compassion was going from strength to strength and had grown to approximately 250 members. He wanted to expand further and so opened a new church building in the south of England, together with a school, in a derelict warehouse on the edge of town. The warehouse was bought with a combination of a large inheritance that Black had recently come into by way of a childless Scottish uncle and donations from nearly all of the church members (Black told his congregation that their gift was a way of thanking God for the blessing of faith). The school was called Tadford School, to tally with the new name that Black had chosen for the church – Tadford Charismatic Church.

That July Mum and Dad decided to go to the church’s weekend conference. I didn’t want to go as it sounded much too boring but they refused to let me stay at home on my own, or go to a friend. They didn’t trust me. I made such a fuss that Mum asked Pastor Collins what she should do. He told her firmly to insist I come too and she told me I didn’t have a choice in the matter. I was so furious and upset that I cried throughout the five-hour drive down south to the church. We arrived late on Friday afternoon and pitched our tent in a temporary campsite in an area of wasteland near to the church, which Black used whenever there was a large weekend meeting. It was a grim place and I was still sulky, telling my parents I didn’t want to go to any of the Church meetings. Mum said that was OK.

So the next morning I wondered off on my own and had a sneaky cigarette while they were praying. Later that day Mum said Ian Black insisted I come to the evening meeting in the church. I tried arguing but it was hopeless. I trailed along with them to the redeveloped warehouse dressed completely inappropriately. I had put my hippie period behind me and now sported a skimpy black top and very short miniskirt that just about covered my Union Jack knickers, which I had made myself. Inside the warehouse there was a garish floral carpet and row upon row of orange plastic chairs, which were filling up rapidly. There must have been at least three hundred people present. At one end there was a stage and I felt that perhaps we were all going to watch a performance. I was not far wrong.

It was very hot and stuffy in the warehouse-cum-church and I felt very bored. I made the point, as young teenagers do, of making sure my parents knew I didn’t want to be there. I refused to stand up when everyone else did to pray loudly or sing. Nor did I join in. Instead I looked around and recognized a few faces from my visit to the Black’s previous church with Mum when I was much younger, but I didn’t acknowledge anyone. In total contrast to me, my parents were obviously captivated, as were most of the congregation. I must have stuck out like a sore thumb.

We had to go through the same routine on Sunday evening, by which time I was so hot and uncomfortable that I suddenly decided I couldn’t take any more. Despite the fact that I was sitting in the middle of a long row and being stared at by Black I got up, squeezed my way through to the end and ran out towards our tent in the temporary campsite. Olivia, who was the wife of the senior pastor, Hugh Porter, ran after me and asked in a doom-laden, intimidating way whether I realized that if I didn’t return I would go to Hell. I was so shocked by her words that I started crying and then let her march me straight back into the church again. The entire congregation had seen how I behaved and my parents were obviously very embarrassed.

Black then seized the moment by asking the congregation to pray for me and led the prayers himself. They were all about saving me, not letting me go to Hell and trying to cast out my ‘rebellious spirit’, which according to 1 Samuel 15:23 is called the sin of witchcraft. I had never been involved in any sort of witchcraft and found the whole thing terrifying. My parents were traumatized too. They knew that to have a daughter labelled as rebellious was a very serious stigma within the Church and kept their heads bowed in shame. I sat quietly next to them, hoping desperately that Black would focus on someone or something else, but when he finished the prayers he said there was someone in the congregation who should go to the new Church school and called out my name.

I couldn’t believe what I was hearing and felt a mixture of shock, fury and embarrassment. Black then called me to the front and, with three hundred people’s eyes fixed on me, prayed over me yet again. He reeked of Brut aftershave and I really didn’t like him. The prayer meeting finished shortly afterwards and I asked my parents what was going on.

Unbeknown to me, my fate had already been sealed the previous day. Mum and Dad had been taken to one side on Saturday morning by Black and the Canadian evangelist Troy Tyson’s nephew, Charles, another visiting preacher, and told that they should leave me behind so that I could go to Tadford School. I am convinced the whole thing was premeditated. The school was in its first year and only had fourteen pupils aged between 4 and 18.

My parents were warned by Black and Charles Tyson that my bad behaviour was a certain sign that I was on the road to Hell. They were told that I was in mortal danger unless they moved fast and put me in the care of the Church. It was stressed that there was not a moment to lose and that my situation was so desperate that they shouldn’t under any circumstances even take me home with them to collect my things. My only chance of salvation was for me to be left behind immediately.

It was Dad’s first visit to Tadford and he decided to talk to Pastor Collins, who was also at the conference, before making such an important and radical decision. Edmund told him it was the best thing that could possibly happen, that it had come from the Lord and was a wonderful opportunity for me. This was a view he later fully acknowledged that he bitterly regretted. Dad’s qualms vanished. Not only did he admire Pastor Edmund, but he was also impressed by the Tadford Church members, who he said were the most devoted, loving people he had ever met. He and Mum were shown round the school. It was housed at one end of the warehouse, where swing doors led to the newly built classrooms. Dad was told that Black had started the school in response to the declining Christian, moral and educational standards that were apparent in the state schools.

The Church had a firm Statement of Faith and members were required to believe in a long list of tenets, such as the Virgin Birth, the Second Coming, the depravity of human nature and a number of other things that meant very little to me but which mostly sounded terrifying. Despite my total opposition to the idea, Dad liked the fact that all the teachers were Christians and thought it was a good, clean, godly environment. Although there was something about Black that made Dad feel uneasy and he couldn’t warm to him, he decided not to tell Mum and instead tried to put it to one side because he was so impressed by everyone else.

Mum told me that Black suggested I stay at the school for two years and was so persuasive that she and Dad felt that, if they didn’t agree, they would be going against what God wanted. I tried to insist I would not change schools, but it soon became obvious that they had made up their minds. I then pleaded with them to take me home so I could collect my things. I had only brought with me what I needed for the weekend, but they refused. I felt frightened, both of being left behind and of all the talk about going to Hell.

My parents stayed on for a couple of days to sort me out for my new life. My miniskirt and tight jeans were completely unsuitable for a Church school and Black told Mum to take me shopping in town for some new clothes. I ended up with a small selection of ghastly, demure three-quarter-length skirts and dresses, long-sleeved blouses with high necks and thick stockings, all of which were designed to make me look respectable and modest. I was not allowed to have jeans or trousers because Black apparently believed they were not ladylike. I hated everything, and felt I was losing my individuality. Instead of being a distinctive teenager I looked like Mary Poppins.

But I didn’t make a terrible scene. It was all much too serious and I was in shock. Instead, I did what I was told and behaved like a robot. After our shopping trip Mum and I came back to the church to buy the school uniform. This consisted of a grey pleated skirt with a white blouse, a maroon blazer with grey trim to match the skirt, a grey coat and a maroon hat, also with a grey trim. It was all hideous. I felt terribly upset that I was not allowed to go home to say goodbye to my friends or boyfriend, who I was particularly keen on, or collect my books, diary and special things.

My parents left on Wednesday morning and I was in floods of tears as they hugged me and said goodbye. I have since learnt that lots of questionable organizations, selling anything from double glazing and commemorative china to religion, often target people and pressurize them into making quick commitments. They persuade them that, unless they make a fast decision, they will lose the chance to take advantage of whatever is on offer.

But, at Tadford on that bleak Sunday in July when my fate and future were about to be sealed, neither of my parents felt under duress, nor were they the slightest bit suspicious of any ulterior motive on the part of Black. Mum had looked round the school, seen well-mannered children and thought that it would be the ideal thing for me. She had always wanted me to have the best opportunities in life and thought that here was my chance.

For my parents it was a hard decision and a sacrifice to leave me behind, both emotionally and financially. Mum even went back to work full-time to pay for my schooling. She also told Black that she wanted me to come home during half-term and the school holidays, and at most stay for a year, but I didn’t know that. Nor did she realize I would be one of only two boarders.

In the cold light of the long car journey home, neither of them felt quite so confident about what they had done. Mum felt guilty and inadequate at not being able to manage me, and about passing me on to somebody else what she felt was really her problem. Dad just felt terrible. They talked about what had happened all the way back. Neither of them slept that night, while several hundred miles away I cried myself to sleep.

Chapter 4

Handed Over to Tadford

I felt totally felt bereft as I watched my parents drive off. My bolshie, know-it-all attitude disappeared and I yearned for Mummy and Daddy to stay with me. I didn’t feel nearly ready to stand on my own two feet and worried that the strange, restricted new world I suddenly found myself in would prove a very lonely place. It didn’t help that after my parents left I discovered that I was one of only two boarders. My heart sank. I couldn’t believe it. I thought that at least there might be the possibility of some late-night fun with other girls in a dormitory. Instead I was told I was going to live in Ian Black’s house with his family.

Ian Callum Fitzroy Black was born in 1939, the son of a prosperous Scottish banker. His father died in the North African campaign fighting for Monty and the Eighth Army when he was 3 and, after being looked after by his mother until he was 8, he was sent off to a private school in the Scottish Highlands, where his father had been a pupil. After leaving school he worked on a large Highland estate as a trainee forester, but, finding that he was less than keen on such a solitary life in the wet wilderness of the Scottish mountains, he soon moved to England in search of work.

For a while he found employment selling agricultural machinery to farmers in Lincolnshire, but, again dissatisfied with his lot, he eventually ended up as a Gas Board employee, becoming a regional sales manager within a couple of years. A dramatic change occurred in his life at his mother’s funeral. Black, who previously had not given much thought to religion or to God, was devastated by his mother’s death and at her funeral, wracked with grief, suddenly understood the meaning behind the arcane symbols and rituals of the Church.

Shortly after this epiphany, Black met Heather, a librarian from Stamford, at a party thrown by one of his colleagues. Initially, the two were friends, but their relationship soon developed and they were married in Lincoln a year after they first met. They moved to a small town nearby, where Black became involved with the local church, taking on the role of lay preacher. Several years later they moved south, where he was able to take up another position with the Gas Board, and bought a rambling six-bedroom house with a large garden.

During this period he started prayer meetings with Heather and another couple, David and Charlotte Snelling, whom they met at church. Others gradually joined them and when there were about seventy regulars they decided to formalize the group. They called themselves the Church of Christ’s Compassion. Shortly afterwards, Black met the Canadian evangelist preacher Troy Tyson, who took him under his wing.

Black and his wife had five children – Ione, Callum, Lucy, Helen and James – and one boarder, a girl some years younger than me called Angie, who was also a pupil at Tadford. I was told that I had to share a room with her. She was sweet and bubbly and had a good sense of humour, but although the difference in our ages was not that big, the difference in our likes and dislikes was enormous. Angie’s bedroom was decorated in pink and very girly, but from the start I could tell she didn’t want to share it with me and I didn’t blame her. Who would want a stranger suddenly turning up without warning who took up space in a room you’d previously had to yourself? But that’s what happened. Black and his wife, together with Angie, had driven to Greece ‘on business’ the day before my parents left, and Alex and Siobhan Scott, a newly married couple who were also founder members of the Church, moved in to look after us. Siobhan taught in the Church school, while Alex was a manager at the local printer’s.

I felt terribly homesick and totally traumatized by what had happened. From being the baby of the family and secure in my parents’ unconditional love, I had been dramatically uprooted and deposited in what felt like an alien land. And I’d had no time to prepare myself either psychologically or physically. I hadn’t said goodbye to any of my many friends. I felt like an amputee who had not only lost all her limbs but had had her heart torn out as well. I had no coping mechanism. I was no longer a child and not yet a woman. Not surprisingly, at first I cried a huge amount. I also wrote to some of my friends telling them I was trapped and asking if they could smuggle me some cigarettes. I didn’t really want the cigarettes: it was just my way of connecting with my friends without losing face. They posted several packets to me but I didn’t smoke them. You weren’t allowed to and I was frightened of getting caught and what the punishment might be.

When Black returned from his trip, Angie insisted she wanted her room back. Black told me he would get the builders in to alter his house to accommodate me in another room and that in the meantime I would be living with Alex and Siobhan in their home. It seemed rather odd to alter his house for one pupil but he seemed determined to have me live there. I had no idea why. Alex and Siobhan lived in a ground-floor flat in the town where the Church had originally started, several miles from Tadford and Black’s house. It was another upheaval for me, especially as there was no one to help smooth my way. I felt totally lost and abandoned.

Siobhan was strict, which was fair enough. She probably found it just as difficult living with a young teenager as I did living with a new family. She often became quiet and distant, and it was difficult to know where I stood with her. Alex, on the other hand, was funny and cracked jokes to ease any tension in the home. He also cooked fantastic pizzas and regularly bought us samples of the comics that his company printed. Between them, it seemed to me, they controlled everything in my life and never allowed me to be on my own. I felt as if I were in a prison and was so unhappy that I refused to unpack for a long time after I moved in.

Inevitably the atmosphere in the flat was tense as every day I’d tell Alex and Siobhan that I wanted to go home. I’d tell my parents the same thing every time they rang me. I was allowed to call them every other day but I noticed that either Alex or Siobhan would hover in the background while I was on the phone, perhaps to hear what I was saying. My phone calls were always the same. I’d plead with them to come and get me, and tell them how much I hated Tadford. Mum and Dad would then both say they wouldn’t come, that I was there for my own good and that everything would be fine because there were so many people at the Church who loved me. Then I’d cry, ‘Please, please, let me come home,’ and even though I could tell Mum was upset hearing me cry, she kept saying, ‘No, you can’t.’ The phrase ‘hitting your head against a brick wall’ kept coming to mind. The more I tried to convince my parents I was in a place that was nothing like the caring community they imagined, the less they seemed to listen. I felt instinctively that it all had dark undertones but I somehow couldn’t put it into words. I certainly didn’t tell them that during Church assemblies we were encouraged to forget our past and think of the Church as our family, even though to my young ears it sounded totally disloyal.

Mum would say things like boarding school is always very difficult for a child during the first few weeks and homesickness is very common. She told me she thought I’d soon get used to it once I made friends. Her responses sounded rather prepared and it crossed my mind whether this was what she had been told to tell me. But I knew it wouldn’t be fine and my fear was confirmed when I went to school for the first time a week after I arrived. It had been hard enough for me to conform to the comparatively free-and-easy school routine at my local comprehensive, but the narrow, restricted and unimaginative curriculum at Tadford School was mind-blowingly boring.

The school day started with religious assembly at 8.15 a.m., followed by lessons. I had been used to a large, open classroom full of children of my own age, all chatting and working together. Now, because there were so few of us, most of the time we were lumped together in one classroom. The younger children sat down one side of the room and older ones like me down the other, and woe betide any child who even tried to look at another. We were so repressed we weren’t allowed to speak during lessons, during meal breaks, or even when we were changing for games.

Despite being deeply shocked, I tried to analyse my situation. On the one hand, I felt it was far too cruel a punishment for someone whose only wrongdoing was to be a rather boisterous teenager. On the other hand, I never doubted that my parents loved me and wanted the best for me. It was all too confusing and I didn’t know where to turn.

Initially the school followed a Christian method of home teaching that basically meant self-learning. This was totally new for me and I missed the stimulation of having other children around me with whom I could share thoughts and ideas. Instead, each of us had our own individual work to do. I was given a work book which set questions, exercises and essays, and when I had finished one set I had to go to a table in the middle of the room, find the book of answers and mark my own work. I then went back and did the next exercise. If any of us needed help from the teacher we had to hold our hand up, and when, eventually, the teacher saw it she would come to help us.

It was all so excruciatingly dull that I used to keep falling asleep. The only thing that slightly cheered me up – proof that I desperately needed even the smallest crumb of comfort that could link me with my family – was the small Tony the Tiger I put on my desk, which I’d bought with my mother just before she left.

One of my worst tasks was to learn ‘memory verses’. This required pupils to learn a different set of twelve verses from the Bible every week. I’d never done anything like it before and was so hopeless at it that sometimes Black rebuked me in front of the whole school, telling everyone that I hadn’t made an effort and I should try harder. He turned up at school assembly about once a month and usually called someone up on to the stage for an alleged misdemeanour. Sometimes it would be a pupil who had showed what he called ‘an improper attitude’. At other times it was someone like me who didn’t do well with the memory verses. Although many of us cried, I didn’t dare discuss his behaviour with anyone else, and if it was an attempt to humiliate me, it worked every time. I felt useless and stupid, and this only served to highlight my chronic loneliness.

At lunchtime the older ones like me had to turn into dinner ladies and help dish up the meal to the other pupils, then wash up all the plates and cutlery by hand afterwards. Although there was a dishwasher in the kitchen, it was never used. I’d had to help out at home, but it had been a family thing, and we’d chat and laugh as we did the washing up or laid the table. Now I resented it, especially as everything had to be cleared up before I could go out to play. At my previous school I always had loads of girls to play with, but at Tadford there were only two other girls of my own age. Luckily I did enjoy the interaction between children of different ages and often played skipping games with the little ones.

There was always plenty of food to eat, but there was no choice and this led to my first confrontation with Black, shortly after he returned from Greece. The meal was Lancashire hotpot and the last time I’d had it – well before I was at Tadford – I was violently sick. There had obviously been something wrong with the meat but I’d decided I didn’t want to eat Lancashire hotpot ever again. Unluckily it was on the school menu on a day he came round to check that we were all eating – in fact he always seemed to be everywhere I went – and he asked me why I was leaving it. I explained what had happened and he replied that it was compulsory at Tadford to eat everything that was put in front of me. I refused and he told me I couldn’t leave the dining room until I had. I showed my fighting spirit by arguing with him for two solid hours until he instructed me to leave the meal on the table and come to his house. We went to the lounge, where Black, plus the head of the school, his secretary Charlotte Snelling, his spokesperson Siobhan Scott and his wife Heather, all key members of the Church, had already gathered. I don’t know if he had summoned them, but the argument was quickly established as five of them against one of me. I kept saying, ‘I am not eating it.’ They kept telling me, ‘Yes you are.’ It continued for another hour until finally I suddenly felt so worn down I burst into tears and agreed to go back and eat the hotpot. It was stone-cold and, in its puddle of congealed grease, tasted disgusting. I wasn’t physically sick but the damage that being forced to eat it did to my spirit was substantial.

Black and the others had won the battle and perhaps felt triumphant that my will had been broken. It was clearly something they considered much more important than my missing an afternoon of school. I, on the other hand, was left feeling emotionally battered, alone and trapped in a place where I didn’t want to be. I did, though, win another confrontation. When the builders finished partitioning Angie’s room at Black’s house and he told me that the new room was now going to be mine, I dug my heels in and absolutely refused to move in. Nothing would budge me and in the end I was allowed to remain with Siobhan and Alex. It was a massive relief, because he still terrified me.

On Wednesdays I had only morning school because I had to help cook, serve and wash up for the weekly group lunch of teachers and other Church staff. One adult and I were involved in catering for about ten of them, including Black, and I absolutely hated doing it. All the other children went home and after the elected adult had cooked everything, she went home too, leaving me on my own to serve, clear up, and wash and dry everything. Perhaps I was chosen because, apart from Angie – who was considered too young – I was the only boarder and didn’t have a real home to go to, which in itself made me feel very bad. I used to find it exhausting and didn’t finish until about 4 p.m. I had school on Saturdays, too. Mornings consisted of classes in dressmaking, which I was useless at, typing and cooking. Black had the idealistic, old-fashioned attitude that women were at their best in the home catering for a man’s every need and believed they should be taught the necessary skills from a young age. In the afternoon I had to play table football. I also learnt badminton and netball.

Normally school finished at 3.45 p.m. and I didn’t do much afterwards, apart from going food shopping with Siobhan and doing my homework. I thought longingly of my gang of friends and how we used to run off laughing together into the woods, or just chill out somewhere and chat non-stop. Now I had nothing to do, no one to do it with and no one to talk to. I felt bereft. I used to talk about anything and everything to my friends, but now my life both in and out of school was largely lived in silence. Although my parents paid full fees for my education, I had to do all the chores for nothing. As well as the Wednesday lunch, after table football on Saturday afternoon I had to help clean the entire school and before Church services I had to clean the toilets, vacuum the enormous church hall and set up the chairs. I thought of it all as slave labour.

Soon after I started at the school, Black instigated a 7 a.m. prayer meeting. It was way too early. I didn’t want to go but I had to, so I dozed throughout. Luckily these sessions were stopped after a few months, I imagine partly because of the ridiculous hour and partly because Black didn’t like small or private gatherings as he wasn’t in control of them.

Right from the start the thing I dreaded most about Tadford was being summoned into Black’s private office. It was called ‘the private haven’ and I feared it because he repeatedly made me feel useless, unworthy and full of despair. My first visit came shortly after the Lancashire hotpot episode. His manner was almost immediately intrusive and within minutes he asked me if I had had sex and if I was pregnant. I was shocked by such crude and personal questions and didn’t want to answer him, but he kept asking me, and in the end I didn’t have the maturity or confidence to tell him it was a private matter and found myself confessing instead. I told him that I had had sex, but that I always used protection and wasn’t pregnant. He then asked me lots of questions about my social life, about what I did and where I went. By the end of it all I felt thoroughly dirty, exposed and humiliated, that what I had done was terribly wrong and that there was no hope for me at all. This one dressing-down also had a long-term effect. It made me feel sex was wrong even if it had been sanctioned by a wedding and I don’t think Peter and I ever experienced true physical intimacy. Despite my huge embarrassment, somewhere at the back of my brain I noted that Black seemed to almost relish the process of breaking me down and extracting my confession.