По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

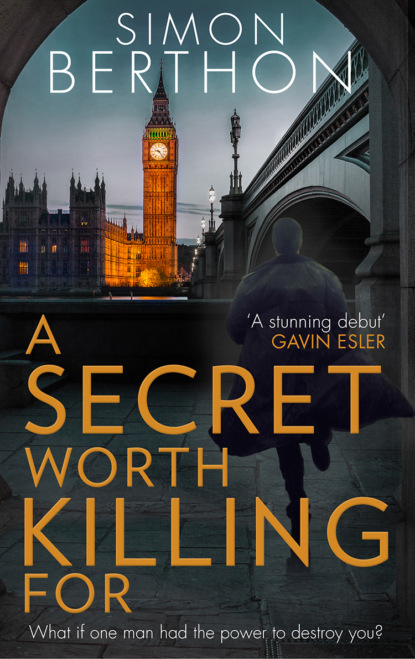

A Secret Worth Killing For

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I’ve never got involved in that way.’

‘Aye, but this isn’t like that.’

‘You promise me it’s just to interrogate him?’

‘Aye.’

‘No violence. No beating. Just propaganda. Just to show you can do it.’

‘Aye.’

‘I need to hear you promise me, Joseph.’

‘That’s fine. I promise.’

‘You give me your word.’

‘Aye.’

‘And Martin approves?’

‘Aye, he would, that’s for sure. No doubt ’bout that.’

She thinks in silence. She remembers the hunger strikers dying when she’s still a girl and the hatred for the British oppressor. Three years later, she shares her big brother’s pleasure when the IRA blows up Mrs Thatcher’s hotel in Brighton. She knows the cause is just but, for her, school, good results, getting to university become the priority. The British state is still hateful, but her belief in the ‘armed struggle’ deflates like a slow puncture.

Yet Joseph has touched a nerve, a lightning rod brushed by lingering guilt. Maybe he’s right and she’s been selfish. She copped out when others didn’t. If what they’re planning is for propaganda, not violence, perhaps it’s just another act of cowardice to keep on avoiding it.

She flicks a glance at him. What if he’s lying? Just talking shite? When did they last let a peeler walk free? She looks away. He’s never lied to her before. Not that she knows, anyway.

Momentarily, a cloud obscures the sun, turning the mountainside an unyielding brown. He’s saying nothing, the quiet oppresses her. Time seems to freeze – the flapping of a bird’s wing high above reduced to the slowest of motions.

His expression has retreated to that beautiful poet’s dolefulness when she’s about to disappoint him. Like those early months after the first full kiss when she wouldn’t go the whole way. Until she did. If she says no to this plea – a plea he’s made with such passion – will he ever forgive her? Might she even lose him? She thinks of asking – but doesn’t want to hear his answer.

She turns. It’s visceral – she just can’t displease him. ‘OK, I’ll do it. Just this once. For you.’ It’s as if the words have tumbled out of her mouth before she even made a decision. A sudden consolation – maybe she’ll still be able to get out of it. She chides herself for even thinking it. Her rational self re-engages. ‘And there’ll be no violence?’

‘Yes, there’ll be no violence.’

She’s told her mother she’ll be in for tea that evening. Rosa has cooked cottage pie and peas, one of Maire’s favourite dishes. She plays with her food, even forgetting to splash it with ketchup, and speaks little.

‘What’s up with you, Maire?’ asks Rosa.

‘Aye, girl, you need to eat,’ chips in her father. Rosa casts him a warning glare to keep out of it.

‘Sorry, Mum,’ she says. ‘Just not feeling hungry. Dunno why.’

Rosa, who’s come to realize that Maire must be sleeping regularly with Joseph, betrays a sudden alarm. ‘Not feeling sick, are you, love?’

Maire looks up with a wan smile. ‘It’s OK, Mum, I’m not feeling sick.’

‘Well that’s all right, then, love.’ At any other time, Maire would hug her mother out of sheer love for her maternal priorities. On this evening she feels only emptiness in the pit of her stomach.

As they’re clearing plates, the front door clangs opens and Martin breezes in, bestowing smiles and kisses all round. Maire suddenly wonders what her parents think of him; whether they even know his prominence in the movement. Politics in general are sometimes discussed at home, but the rights and wrongs of violence are no-go. It’s only, and infrequently, mentioned when she’s alone with her brother. They must suspect – they’d be blind not to – but have decided it’s best to keep out.

‘Hey, little sister, you’re looking gorgeous as ever,’ Martin declares, not a care in the world.

Maire attempts a show of response but recoils. Surely he must know about Joseph’s conversation with her today and her acquiescence. She wonders at his bravado, and the masking of his double life as happy-go-lucky son and IRA commander.

He notices her listlessness. ‘What’s up, kid?’ How can he even contemplate such a question? She searches for a hint.

‘It’s nothing,’ she says, ‘just a chat I was having with Joseph.’

‘So how’s the world’s greatest revolutionary doing?’ There’s an edge of condescension in her brother’s tone. Again she flinches at his duplicitousness.

‘Full of schemes, as always,’ she replies.

‘Aye, that he is,’ says Martin. ‘That he certainly is.’

He’s giving her nothing. Literally nothing. No comfort, no support, not a hint of empathy. Perhaps that’s the way it has to be.

They decide to try it the next Saturday night. More people milling, more cover, guards more likely to be down.

She prepares. She’s cut her hair, taking three inches off the long auburn tresses, and used straighteners to remove the waves and curls. Instead of the hint of side parting, she brushes the hairs straight back, revealing the fullness of her face and half-moon of her forehead. She examines the slight kink in her small, roman-shaped nose. As always, she dislikes it. She applies mauve mascara and brighter, thicker lipstick to her cupid lips. She wears a black leather skirt, above the knee but not blatantly short, and a bright-pink, buttoned blouse that doesn’t quite meet it in the middle. The gap exposes a minuscule fold of belly. She pinches the flesh angrily. Through the blouse, a skimpy black lace-patterned bra, exposing the top of her firm small breasts, is visible. The overall effect is not a disguise, just a redesign. While it doesn’t make her look cheap or a tart, she’s unmistakably a girl out for a good time.

She’s steeled herself, told herself it’s just a job. Clock on, clock off three hours later. Thoughts of how to pull out have besieged her every minute since she said yes – even though she instantly knew she couldn’t. But once she’s done it, that’ll be it. Never again.

She’s kidding herself. Once you’re in, they’ve a hold over you – you’re complicit. She thinks of her brother – did he recruit Joseph? How did they get their hold over him? She remembers that tightness in his face. Did they ever need to?

She arrives just after 8.30 p.m.

As agreed, she finds a bar table with two chairs, sits down and appears to be waiting for her date to arrive. A waiter comes – she orders a vodka and Coke.

He’s already there, sitting at the bar. The description, both of him and his clothing, is accurate. Late thirties, sandy hair retreating at the sides, a ten pence sized bald spot on top covered by straggles of hair that offer an easy mark of recognition from the rear. On the way in, she’s been able to catch more; the beginnings of a potbelly edging over fawn-belted, light-brown trousers. Brown loafers and light coloured socks, dark-brown leather jacket. Perhaps the brown is an off-duty discard of the policeman’s blue. On his upper lip, a pale, neatly trimmed moustache. Brown-rimmed, narrow spectacles sitting on the bridge of a hook nose. Somewhat incongruously, pale blue eyes. From those first glimpses, he seems a nicer-looking man than she expected. A relief, given one part of the task that lies ahead. But ugliness becomes a victim more easily.

They say he usually drinks one or two before chatting up the bar girls and waitresses. Around 9.15, when she’s been waiting three-quarters of an hour for her elusive date to arrive, she walks towards the bar. She places herself beside him.

‘Another vodka and Coke,’ she demands, louder than necessary.

He turns to her with a raise of the eyebrows.

‘Bastard hasn’t shown,’ she says, glaring at him as if to say, ‘Whaddya want?’

‘He’s a fool.’ He eyes her with frank admiration. The accent is English, south not north. A confirmation.

‘I’m the eejit,’ she says. Her drink arrives and she makes to return to her seat.

‘You might as well stay and chat till he comes. I’ll pull that stool over.’

She hesitates. It seems too easy. What’s this man really like? From nowhere she imagines him hitting her. Where did that come from? Nerves, just nerves. Her heartbeat is racing. She gathers herself. ‘I left my coat at the table.’