По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

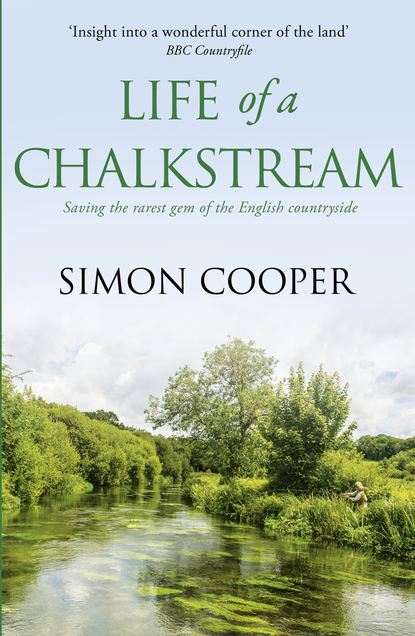

Life of a Chalkstream

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Gavelwood, the land, the river, side streams, brook and water meadows, takes its name from a wood that makes up part of this tiny, forgotten part of England. The woodland, a mixture of native trees like oak and ash, is as unkempt as the meadows it borders. Nobody knows where the name came from, but it is clearly marked on the deeds of ownership. The medieval word ‘gavel’ meant to give up something in lieu of rent, so maybe in some distant century the lumber was exchanged for tenure. But here today I am not here for any timber, it is the river that is the draw. A beautiful chalkstream called the Evitt that runs gin-clear, the perfect home for fish and water creatures that thrive in a habitat that is as endangered and as worthy of protection as any tropical rainforest or virgin Arctic tundra.

The water that flows through the chalkstreams is a geological freak of nature, almost unique to England. There are a few chalkstreams in Normandy, northern France, and one is rumoured to exist in New Zealand, but taken as a whole 95 per cent of the planet’s supply of pure chalkstream water exists only in southern England. The water I watch flow by in the river today fell as rain a hundred miles to the north six months ago, was deep underground yesterday and will be in the English Channel in a few hours’ time, a cycle that has been repeating for tens of thousands of years since the last ice age ended.

A chalkstream river valley today is a tamed version of how it started out. After the ice age it would have been little more than a vast, boggy marshland, with no river to speak of but rather thousands of streams, rivulets and watercourses that randomly flowed this way and that. At some point in time, it is hard to say exactly when, the early Britons must have started to use the valleys for a purpose, initially farming, which involved draining the land. Inevitably drainage involved reducing the myriad streams to a few channels, which in turn became the rivers that have evolved into the chalkstreams we have today.

It has been a mighty long process: five or six millennia for sure. The barges that carried the stones for Stonehenge were brought up what is now the Hampshire Avon, probably widened and straightened for the purpose, from where it enters the sea at Christchurch Harbour 33 miles from Amesbury, the Avon’s closest point to Stonehenge. But these incremental activities changed the river valleys very slowly, and it was the advent of the watermills that was to prove the penultimate step on the way to the chalkstream valleys we see now.

Again it is hard to pinpoint precisely when watermills became a regular part of the landscape. One thing is for sure, there are plenty listed in the Domesday Book, so it is fair to assume that the valleys were taking shape to meet the requirements of water power by this time. Essentially the mill wheel requires a good head of water to drive it, so a special channel would be dug to supply the water to drive the wheel. This ‘millpond’ would be controlled by a series of hatches, which when opened would turn the wheel for a few hours. Once depleted, the hatches would be closed and the millpond given time to refill from the river and streams.

The unintended outcome of all this would be to drain the land in the immediate vicinity, which in turn created the most wonderfully rich grazing pasture on the alluvial soil left behind after many millennia of flooding. This bounty of nature did not go unnoticed, so over the centuries that followed the river valley was gradually drained not just for the mills but for farming. The water was concentrated into a single channel which is the River Evitt today, supplemented by the side streams and ditches that provide the drainage.

But the story has one last twist. Having deprived the land of the flooding, the farmers realized that they were taking away one of the very things that had made it so productive in the first place – the nutrient-rich water that every winter washed over it. So around the seventeenth century, as the agricultural revolution took hold, landowners realized that drainage alone was not the answer and that managed flooding would dramatically increase the yield from the land, so the water meadows came into being.

By digging carriers, or leats, quite literally streams that carry water away from the main river, redirecting side streams, filling in others and creating a series of hatches to manage the flow of water, the farmers were able to use the winter and spring flows to flood the meadows from February to May. The term flooding is something of a misnomer; deep, static water over the grass would do little more than rot it away. The skill in floating, the creation of a water-meadow system, is to keep a thin layer of water constantly moving over the surface. The warmth of the water and the protection from frost, plus the nutrients carried in from the river, allow the grass to grow earlier and quicker. When ready for grazing the cattle would be let in, to be taken off when they had eaten it down and the land reflooded. If this all sounds a laborious process, it probably was. It was far beyond the daily regime of the farmers who banded together to employ a drowner, or waterman, who regulated the flows.

Today drowners are a long-distant memory, the advent of artificial fertilizers sounding the death-knell for the meadows from the early 1900s. When the watermills finally stopped grinding a few decades later, the raison d’être for this integrated water system would have all but disappeared except for the fact that somewhere along the line, in the period when the chalkstream valleys went from marshes to meadows, the brown trout had become the dominant species in the river. Never ones to miss an opportunity, anglers soon followed, first for food and then for sport, at which point the chalkstreams became a byword for angling perfection. The drowners and farmers were replaced by river keepers who lavished care on the rivers far beyond the basic needs of an agrarian England.

Fishing, angling, call it what you will, with an insect, worm, net, hook, spear or anything else that captures the fish, is as old as mankind. But as a pastime, done for the pleasure of the activity as much as for the outcome, it has to be credited to the Victorians. They did of course have their antecedents. Dame Juliana Berners, an English nun, wrote A Treatyse of Fysshynge wyth an Angle in 1496, which can be claimed as the first book about fishing as a sport, although she has been eclipsed in history by Izaak Walton’s The Compleat Angler, which followed 150 years later. But these great anglers and writers were exceptions; for most people trout were there for catching and eating with the minimum of effort. So why the Victorians? Well, it was a coming together of wealth, leisure time, technology, the railways and the insatiable curiosity of a few individuals.

Gavelwood today is a tiny proportion of what was once a huge country estate, running to thousands of acres and 11 miles of the River Evitt. In fact the entire river valley, encompassing all 30 miles of the Evitt from source to estuary, was in the ownership of just three families. Hardly very egalitarian, but those were the times, and for fishing, and the chalkstreams in particular, they proved decisive for the future. Once the fishing craze caught on amongst the landed gentry the rivers became much more than farmland irrigators and power sources for mills. River keepers were employed, banks maintained, fish reared for stocking, river weed cut, predators removed. The water meadows were kept in good shape not just for drowning but fishing as well. Suddenly the owners of the great estates began to value the rivers for the sport they could offer.

As the railways made the countryside more accessible, great houses hosted grand fishing parties. Gunsmiths turned their hands to fine reels, rods, lines, hooks and flies, using the latest techniques and materials. Weekly magazines like The Field and Country Life lionized innovators like Frederic M. Halford, a wealthy industrialist in his own right, who codified fly-fishing in a single book. Fly-fishing went from an obscure pastime to the ‘must do’ sport in a matter of decades. If you fished for salmon Scotland was the place to head for, but for brown trout dry fly-fishing the chalkstreams of southern England were the ultimate destination.

The mayfly period, or Duffers Fortnight, became as much a part of the English season as Ascot or Wimbledon. The future kings of England were elected president of the world’s most exclusive fly-fishing club. Fine tackle manufacturers received the Royal Warrant. Government ministers cut short cabinet meetings to catch the train in time for the evening rise. Eisenhower took time out from the D-Day preparations to fish the River Test. As the fly-fishing craze spread across Europe and the Americas, visitors from abroad took home stories of the fabled chalkstreams which took on deserved iconic status. But time, money and enthusiasm are not always limitless, and as I walked around Gavelwood on this late September day I could chart the progression from a chalkstream paradise to something that is today a shadow of its former self.

Nobody set out to make it so. It was simply another twist in the evolution of the rural landscape. In succession the water meadows, watermills and finally fly-fishing were no longer part of the daily life of Gavelwood as the ownership changed to commercial farming. No longer were the myriad carriers and streams of any use, so they were left to atrophy. The meadows were ploughed, fertilized and sprayed for crops. The river was left untended. Gradually as the diverse habitat disappeared so did the creatures that inhabited the river, banks and meadows.

But three or four decades of neglect did not put Gavelwood beyond redemption.

3 (#uf4839420-6584-57e9-acde-ba57b9abc0f0)

WORK BEGINS (#uf4839420-6584-57e9-acde-ba57b9abc0f0)

AS EVER, MY ancient leaking Land Rover provided little protection against the sideways rain of the late October day as I drove down the potholed track to the river. I had hoped for better weather. This was to be a landmark day in the restoration of Gavelwood: our first step towards the re-creation of something special, where the fruits of our dreams and expectations would, at least in part, be rewarded. After a month of back-breaking work North Stream was ready to be opened to fresh, gin-clear, chalkstream water from the Evitt for the first time in four generations.

North Stream is an ancient carrier that connects the main river – the Evitt – with another side stream we call Katherine’s Brook. I say ‘connects’ in the loosest possible sense, because barely a drop of water has flowed through it in living memory. Along its entire length – about half a mile – it should really be a fast-flowing little river that takes the excess flow from the main river into Katherine’s Brook, which in turn will rejoin the main river some 3 miles downstream. Instead the stream was a morass of fallen trees, roots, bushes, debris and mud.

I parked up close to the junction of the main river, where there is a set of hatches, built long ago, to control the flow of water into North Stream. Back in July, when we had first conceived the restoration plan, those hatches were almost invisible. On the river side a thick margin of reeds had choked what would have been the funnel-shaped entrance to the river. Today, the weeks of work had revealed three upright pillars of limestone, about the size of a tall man, set into the bank. They are slightly pockmarked in places, but generally washed smooth by centuries of water. The fronts of the pillars are V-shaped to deflect the current, and running down each inside edge is a groove into which are slotted oak boards – these regulate the amount of water that flows from the main river into North Stream. The oak is newly sawn, a lovely bright honey yellow that would, in a few months, turn to a silver grey. But for now their newness is proof that the hatches are repaired and ready to play their part in the rebirth of North Stream.

With everything Gavelwood has to offer – miles of main river, side streams and hundreds of acres of water meadows – North Stream might seem an unlikely candidate for the first step in the restoration. At first glance, if you noticed it at all, it looks marginal. It is not very wide – a reasonably agile person with a short run-up could leap it in most places – and is fairly straight, without any particular features that catch the eye. My suspicion is that given a few more years it would have disappeared entirely to become a soggy ribbon across a water meadow, its original purpose long forgotten. But the first time I saw it I knew it had the potential to become the most wonderful spawning stream for trout, salmon and maybe even grayling.

On that first visit as I walked down the bank, occasionally pushing aside the branches of the bushes and trees that choked the channel, a few small, bright pockets of gravel glinted back at me, lit by the rays of sunshine that cut through the gaps in the foliage; the gravel kept free from silt by the spring heads that bubbled up from deep below. Loose, well-oxygenated gravel is vital for spawning trout. It is the place the gravid female lays her eggs and the home for the ova as they metamorphose from eggs to tiny fry, out of sight from the many predators that see them as a nutritious food source. My hunch was that beneath the silt and overgrowth North Stream was a gravel haven and finding out was not going to be very difficult.

In fact it proved harder than I thought. A combination of wicked stinging nettles that are at their fiercest in the high summer, plus the barbs of the hawthorn and the clawing tendrils of the wild roses forced me back each time I tried to push my way down the bank. Eventually I came across an ash tree that had fallen across the river, flattening my access. Using a tree branch for support I slowly lowered one foot into the shallow water, letting my weight push it down through the thick mud, hoping that I would make contact with the riverbed before the water reached the top of my boots. Fortunately I did, and the firm base beneath my boots told me I had reached the best kind of rock bottom. I jiggled my feet and through the thick rubber soles I could feel the friable gravel. As I waded upstream I kicked away at the silt bottom to expose what I had hoped for – gravel the entire length of the stream. The further I waded up the more certain I became of the plan to have North Stream ready for autumn spawning – with clean, bright gravel where the trout eggs would be nurtured by a constant flow of fresh water from the main river. Yes, the timetable was tight and yes, the work would be hard, but at that moment to miss yet another year, after the decades of decline, seemed positively criminal.

I plotted the timetable as I walked. We needed to be finished by 1 November. River Evitt trout typically start the act of spawning around mid-December, but they would need at least a month to grow familiar with their new environment before beginning courtship. To have us clumping around would put an end to that before it even started. The trout fishing season ends on 30 September. It would be tempting to start clearing the stream earlier, but our downstream neighbours, not to mention our own anglers, who regularly fished at Gavelwood, would not thank me for sending muddy water and debris their way. So we had four weeks to take what looked like a clogged ditch and transform it into a piscatorial love nest and nursery.

There are two ways to restore a river: the easy but expensive and the cheaper but hard. The easy but expensive way involves signing up an ecological consultant who will start by carrying out a painstaking survey (at your cost) of the river and surrounding land. Every tree will be plotted, the curvature of each bend delineated and the depth of the pools plumbed. Soil and water samples will be analysed, flow rates monitored and the wildlife censused. In return for a mighty fee you will receive a mighty document with maps, drawings, graphs, commentary and appendices. You’ll read it. Actually you won’t – you will read the two-page executive summary at the front and glance through the rest. Fortunately your fee includes a presentation, so you head for the consultancy offices. Having been ushered into the boardroom by a receptionist you are then glad-handed by the team. Everything is very exciting and the possibilities immense. You can only agree, but how do I do it, you ask. At this point the meeting gets serious. Sitting across the table from you is the Chief Executive, who takes a copy of the report and places it squarely on the table in front of you.

‘May I be frank with you, Mr Cooper?’

My advice to you at this point is to say no and leave; no good can ever come with a person who opens with this line. But you are curious, so you invite the man to continue. He opens by telling you what you know already. The report on the table is the perfect guide to do-it-yourself restoration. Everyone around the table knows this, but our wily Chief Executive casts a fly into your path he knows you will take.

‘How much were you planning to spend on the project?’ he asks innocently. You quote a number, faintly embarrassed that you thought it could be done for so little. He purses his lips. ‘Here’s the thing,’ he says. ‘You will do an OK job with that budget, but this is such a very exciting project, the potential so immense, that we should think big. Let’s quadruple your budget, apply for funding, and in the end you’ll only have to dip into your own pocket for a fraction of what you originally thought.’

The lure of his fly is too much and you rise to it like the greedy chap you are. The thought of twenty grand’s worth of work for the cost of five is too much to resist. Leaving the room an hour later you have been truly hooked and landed. The consultants are delighted (but not surprised) with a new contract to seek out funding and manage the project when the grants roll in. You are of course still on the hook for their fees if the funding never shows up, but that is a discussion left for another day.

But I don’t much like easy and expensive. It takes too long, the finished job is never as good, and it seems a bit immoral to me that half the money will go to consultants, however expert. And quite frankly, where is the fun in handing the project over to strangers? I wanted to get my hands dirty: stand in the river, look upstream and with a trout’s-eye view of the world fine-tune the work as I went along.

But all this was still ahead of us when my team and I gathered in August to make plans for North Stream’s restoration. It was not the best month to do our kind of survey – the undergrowth at its most dense, the flow almost non-existent – but we could see enough to make some educated guesses. The work was going to be done by Steve, Dan, myself and a team of irregular helpers.

Steve is the closest thing we have to a full-time river keeper. A retired fireman who looks forty but is in fact fifty-five, he runs triathlons just for the hell of it. He can, and does, work all day felling trees, cutting weed and hammering in fence posts. He is in fact more of a coarse angler, and Gavelwood sort of inherited him when some local lakes closed down.

Dan is young. We tease him for being young and he mocks us for being old. In his early twenties, Dan is on a sabbatical year from his university ecology course. I have a feeling he may have dropped out for good, but it is a suspicion I have kept to myself.

The irregulars are a band of loyal fishermen and locals who simply like to help. They turn up as they wish, or Steve will put out a call when he needs some extra hands. It seems to work and every few months I put some cash behind the bar at the pub for an evening of merriment. Work on the river next day is sparsely attended.

On that particular August morning Steve, Dan and I had gathered at Bailey Bridge, a steel latticework bridge of the same name that was invented by the British army. You used to see them all over the river valleys at one time, but most have rotted and rusted away. Built of light steel and wood, in sections small enough to be lifted into place by hand, they were ideal for bridging meadow streams. Designed to take the weight of a tank, they were much loved by farmers, not least because they were easy to ‘liberate’ from the nearby military camps on Salisbury Plain if you drank with a friendly sergeant major.

Our bridge looked to me like it was getting towards the end of its life, but we estimated that by replacing a few of the wooden boards and repainting the metalwork we could eke a few more years out of it. I had my doubts about its inherent strength but Steve was prepared to test it out by the simple act of driving a tractor and laden trailer over it. Sometimes he worries me.

The first decision we needed to make was whether to clear one or both banks along North Stream. Both sides were equally overgrown, and there are merits whichever way you choose to go. In sheer practical terms opting for a single-bank restoration halves not just the work required for the initial clearance but also regular maintenance in the years to come. With our tight timetable it was an attractive proposition, but ultimately we had to decide on what was best for the wildlife, the river and the fishing.

Stepping off Bailey Bridge and towards the stream, our path was blocked by chest-high stinging nettles. Nettles are no great friends of ours – sure, they are much loved by caterpillars, who feed voraciously on them, but for the river keeper and angler they are a menace. They grow fast, crowd out more useful bankside plants and sting like crazy. Fortunately getting rid of them is not hard, at least if you have someone like Dan to do the work. Nettles are nitrogen addicts – in their effort to run wild they suck every last drop of nutrient out of the ground. But when they die back in the autumn the rotting stems and leaves put nitrogen back into the soil ready for next year. However, cut the nettles down and rake away the cuttings and you deprive the next generation of their nitrogen fix. Other species soon encroach on the ground left bare and new plants thrive in place of the nettles. For Dan a couple of weeks with a scythe and rake were on the cards.

Beyond the nettles and bordering the stream was the scrubby woodland that ran the length of North Stream. On both banks it was 10–15 yards wide, because some years earlier it had been fenced off. The fence was pretty much all but gone, save for a few posts and rusting strands of barbed wire that would no doubt trip us up at some point. The main growth was really stunted hawthorn, which had done us something of a favour in the absence of the fence, by keeping the cattle away from the banks and out of the river. Pretty in its own way, and home to the hawthorn fly, we mulled over how many of these bushes-cum-trees should stay, be trimmed or cut down. I am a huge fan of hawthorn. It is the constituent element of every hedge in the chalk valleys and in April its vivid lime-green leaves and white or red flowers are the first tangible proof of spring’s arrival. Admittedly the flowering bushes do emit the most awful stench, which makes you think there is a rotting corpse under every hedgerow, but once you know what it is it does not seem that bad.

What’s more, the hawthorn fly or St Mark’s fly (Bibio marci, so called because it hatches around St Mark’s Day on 25 April) causes much excitement among fly-fishermen in the first few weeks of the season, not least because trout go on quite the feeding frenzy when these clumsy fliers drop onto the river surface. The fly has no real connection with the river, so why trout go mad for these freakish-looking creatures is a mystery about which one can only hazard a guess. At first glance the hawthorn fly looks like an athletic housefly, but at second you’ll see its long spindly legs dangling below it, like the undercarriage of an aircraft, with big knuckles for knees and so hairy you might even stroke them. The flies don’t live for long, maybe a week at most, having emerged from larvae in the soil beneath the hawthorn bushes. Once hatched they hug the hedgerows for protection from the wind, but from time to time an unexpected gust will whisk them across the meadows. From this point on things get tricky. They are, without shelter, the most hopeless fliers and you will see them buffeted by the breeze. Occasionally when the wind drops they regain control, but it will be short-lived and once over water they will plop onto the surface. Unable to break free of the surface tension they are easy pickings for the trout.

Along the length of North Stream and among the hawthorn are a few spindly ash, plus some alders, clumps of hazel, brambles and wild roses. The trees we wanted to keep we marked green, those we would thin, blue, and the rest – marked red – were to be cleared. It soon grew abundantly obvious that on this bank there was not much to preserve, whilst on the opposite side pretty well everything, bar a few branches that were falling into the river, could remain undisturbed as a sanctuary for the creatures that live along the riverbank.

Part of the restoration process is about letting light back into the river and onto the riverbed itself so that the weed there can grow. The term weed does these river plants like crowfoot, starwort and water celery something of a disservice. Weed implies that they are invasive and bad, but the reverse is true. The right river weed, in the right river, is home to nymphs, snails and all manner of tiny aquatic creatures. It provides cover for fish, shade from the sun and refuge from predators. And as a filter for the water, a healthy river needs healthy weed, and that will only grow with sunlight. It is hard to say anything bad about weed, and a chalkstream without it is on a downward spiral.

Removing a fair amount of the thicket growth along the south-facing bank was going to suit us very well. In this respect clearing the north bank alone would not have helped, because as the sun tracks east to west across the sky during the day it would have left the stream perpetually in shade. If you ever doubt how bad perpetual darkness is for the ecosystem of a river, glance under a bridge one day; it will be as bleak as the surface of the moon. That said, our work was far from about eliminating all shade; trout and all the creatures thrive best where there is a mix of light and dappled shade, so before we took the saw to any bush or tree we cocked our heads to each in turn to decide stay, trim or go.

All the way up North Stream the stream itself was no great issue for us. Sure there were plenty of branches and stumps to pull out, but the dark shade had pretty well prevented anything growing. Once the obstructions were removed the sheer volume of water over the winter would flush away the mud and slime. That was of course always assuming we were able to open up the Portland hatches.

Removing the decades of compacted silt could be done by hand but it would be long and laborious, so we elected to bring in a digger to do the job. Machines are great, but sometimes you have to go easy with them or risk doing damage to the very things you wish to preserve. The Portland hatches were a case in point. They had stood the test of around 500 years because they had been carefully constructed with strong foundations. Smash those with the digger bucket and our problems would multiply.

Steve produced a steel rod with a T-bar handle. Jumping down onto the silt he pushed the rod into the ground until at around 5 foot down we heard a muffled clunk. He tapped the rod up and down twice to confirm that he had hit something solid. Over the next hour, working like an avalanche rescue team on snow, we each took a rod, gradually mapping out the depth and extent of the stone slabs ready for the digger to do the hard graft once the season had closed.

There is never what I would call a really good time to embark on a restoration; every month, every time of year has its merits, but inevitably there is disruption to the natural order of things – removing the bad and encouraging the good. The bad comes in all shapes and sizes: people, fish, animals, mammals and even plants. Yes, there are even bad plants on the chalkstreams, the most invidious of which has its origins on the foothills of the Himalayas.

My problem with Himalayan balsam is that I rather like it. The tall plants stand high above the surrounding vegetation in vast swathes and the light red-pink funnel flowers are a sea of colour that gently waves in the late summer breeze. The smell from the flowers envelops the riverbank. It is a dry, sweet smell – lightly medicinal and cathartic at the same time. It is completely alien to anything else that grows in the meadows. It looks different, smells different and has the most amazing way of distributing seeds when the flowers have died and the tall plants are denuded of leaves, just leaving brown seed pods. Brush past the balsam and the seed pods burst with an audible ‘pop’, shooting their kernels yards around. It happens with quite some force; you will feel the sting if they bounce off your face or hands. Young children love to grasp the plant at the base, shaking it with all their might while the rat-a-tat of seeds sails harmlessly above them.

Imported as an exotic species from Nepal in the early 1800s, Himalayan balsam is now established in Britain, but has had particular success on rivers where the seeds, which can survive two years, are distributed by the water. As a single plant it is no great problem, but that is not in the nature of Himalayan balsam. It is an invader that grows faster than any native plants, shading out and eventually killing all others. Walk the banks in October where the balsam has taken hold, and the area looks like a wasteland. Everything beneath the balsam is dead. In truth it looks like the ground has been sprayed with a toxic weedkiller, and come winter, that soil is bare and ripe to be washed into the river.

Fortunately for me and river keepers everywhere, Himalayan balsam is an enemy that can be defeated. For now, in October, there is not much I can do, but come early summer when the balsam pops its heads above the surrounding growth we will walk through the meadows pulling out the plants by hand. Mercifully they are shallow-rooted, so they come out easily or snap off at the base like soggy celery. However, not all my enemies are so easily defeated.