She’d tried to reason with him. The science of true subliminally enhanced emotional response was new, she’d explained. Unlike the cassette tapes of years gone by with their spoken message whispered through soothing music, actually effecting a specific, targeted emotional change via brain waves. Her psychological focus was human sexuality, not anger. She’d never studied how sound related to human perception of negative emotions. She wasn’t a neurologist, she didn’t know where anger was triggered in the brain, so she couldn’t create a program that would target it.

He’d pointed a fork dripping with egg and bacon grease her way and suggested she get her ass to learning before he lost patience. Then he’d had her escorted to what he called her new lab. A room barely bigger than the one she’d slept in, it was fitted with a desk, a workbench and two chairs. A used and slightly beat-up-looking stack of audio and digital equipment littered the bench, including a processor, data streamer and a closed-loop stimulator. Next to that was an array of psych books and a digital tablet.

After ordering her to work, he’d left her there until this morning. With bargain-basement equipment that did her no good, a pile of books that meant nothing, no research access and a ton of time for her brain to scramble between terrified images of what would come next, to blinding hope that someone would get her the hell out of there before she had to face the rat again.

But here she was, pretty much running out of hope.

So she was tuning him out. The games, the threats, the fear. Four years of yoga breathing and tapping into her long-abandoned meditation practice were all she had left.

With that in mind, and yes, because she’d seen the irritation on his face, she closed her eyes again and inhaled deeply through her teeth.

“You’re doing it wrong,” the whiny voice snapped. “You’re supposed to inhale through your nose. It’s a filter. Are you sure you’re a scientist? You don’t seem to know very much.”

Alexia’s eyes popped open, followed quickly by her mouth. Luckily, she saw the gleam in his beady eyes before she spit a word of defense.

She clamped her lips shut.

“I’m not surprised, actually,” he mused, contemplating the slab of bloody red steak on his fork. “Disappointed, but after your lack of progress these few days, not surprised at all.”

Shifting that same contemplative stare to her face, he wrapped his fat lips around that huge chunk of meat and chewed. A trail of blood dripped down the side of his mouth, over his receding chin, then plopped on the front of his white shirt. He didn’t seem to notice.

He was waiting for her to rise to the bait.

Alexia refused.

His eyes gleamed, as if the more defiance she showed, the happier he was.

“I’d have thought a woman like yourself, with all those fancy degrees and who’s made a show of thumbing her nose at her family, would be a little smarter.”

Alexia’s blood froze. She’d figured this was all about her research. But if he knew who her family was, that changed things. Was this really about creating an anger switch? Or did it have something to do with her father? If the latter, why the elaborate charade?

“Please,” she said, trying to sound reasonable and calm instead of freaked out and frenzied. “Just let me go. I can’t do what you’re asking. You’re smart enough to have researched the technology yourself. You know the equipment you have here isn’t adequate. The research isn’t cohesive enough to work with.”

Yes, she was playing fast and loose with the terms smart and research there. But she figured saving her life was a good enough excuse to employ a few lies and fake flattery.

“You’re on the verge of a breakthrough. You just did an interview on TV last month. It’s in the papers, other scientists are commenting on it in their blogs,” he said, shaking his finger at her as if she had done something naughty.

Blogs? Seriously? Alexia’s nerves stretched tight, ravaged from alternately fearing for her life and peering into corners looking for the hidden cameras that would prove this was all some elaborate, sick hoax.

“So there’s no reason you can’t take the same research and give it a little twist. Passion is just as easily channeled into anger as it is into something as trivial as sex.”

“I told you, it’s not a simple matter of flipping a switch. My research has been focused on the physical body and healing. Not on the emotions. I don’t know how to tap into anger, fury or any of the other destructive emotions you want.”

His contemplative stare didn’t change. He didn’t even blink. Maybe he was more snake than rat.

“Perhaps you just need a little motivation,” he decided. That damn finger still tapping, he tilted his head to one side as he gave her body a thorough inspection. Her skin crawled as if someone had just dipped her in a vat of lice.

“You’re a pretty woman. Robert—” he indicated the henchman who most often guarded Alexia “—has expressed an interest in your charms. Perhaps I should reward his exemplary service, hmm?”

Her eyes blurry with fear, Alexia’s gaze slid to the henchman, whose own beady eyes were gleaming with lust. Bile rose in her throat, but she was too paralyzed with terror to even throw up.

“Of course, Robert did go a little far with his last reward,” the rat continued in that same contemplative tone. “She was useless to us when he was through. It’s hard to see much through the snowstorm, but if you look out your window, you can see her grave just on the other side of the electric fence.”

Black dots danced in front of Alexia’s eyes, her breathing so shallow she didn’t think any oxygen was reaching her brain.

“I’m more inclined to wait on the reward,” he said slowly, pausing to sip his wine, giving her time to take a small step back from the panicked cliff she’d been about to dive over. “Myself, I find rape a poor persuasion. If the mind is broken, the body isn’t good for much except more of the same. And I need your mind in good working order.”

Alexia wasn’t sure if her mind would ever work again, even as it shied away from the hideous images she couldn’t stop from running through it.

“So many possibilities to consider,” he mused, now tapping his lower lip as if that would help him decide. “I’ll have to sleep on it and let you know in the morning.”

His smile slid into a smirk. “In the meantime, I suggest you trot on over to the lab and see what you can do now that you’re a little more motivated.”

“You can’t do this,” she breathed, half denial, half prayer.

“I can do anything I want,” he said with a dismissive wave of his hand. “Go. Robert will see you to the lab.”

Alexia got to her feet, subtly resting her fingertips on the edge of the table until her knees stopped shaking enough to support her.

“Go on,” the rat ordered, flicking his fingers toward the door. “Get to work.”

Yeah, she decided, trying to find the fury through the choking waves of fear threatening to overwhelm her.

He was definitely a snake.

9

FOURTEEN HOURS LATER, Alexia finally understood what it was to have fear leach every ounce of energy from a body.

She was completely numb.

She cradled her head in her arms and tried to stop her teeth from chattering.

From her bare toes—made colder every time she glanced at the window to see the white blizzard of snow swirling outside—to the top of her aching head, she was ice.

Desperate for a focal point other than the hideous visions her captor had stuck in her head, she had resorted to digging into the books. Somewhere around hour three, she had filled a notebook. Not anything that’d produce the results he wanted. But maybe enough to make it look as if she could, which might buy her some time.

The words were a blur on the page now.

It took Alexia a minute to realize that was because she was crying, her tears making the ink run.

A sound, barely a whisper of the wind, caught her attention. Her body braced. Tension, so tight even her hair hurt, gripped her. Barely daring to breathe, she shifted her head just a bit in her cradling arms so she could peek over her shoulder.

Crap.

She blinked, trying to focus on the figure standing inside a window that should be too tiny for a body to fit through. The freezing air wrapped around her like a shroud, making her blink again.

Her shivers turned to body-racking shakes. Alexia still didn’t bother raising her head.

“I sure wish hallucinations came with temperature control,” she muttered to her biceps.

The figure moved. She blinked a couple of times, waiting for it to fade. But it came closer.

And closer.

The closer it came, the more sure she was that this was pure fantasy, woven by a generous mind eager to give her a sweet escape.

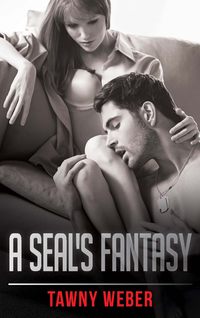

“Let’s go,” the fantasy ordered. She wasn’t surprised it sounded like Blake. All her fantasies revolved around the sexy SEAL. Most were naked, though, and the only shivers involved were sexually inspired.

“Sure, I’ll go with you,” she bartered in a teasing tone. Might as well humor her mind, since it’d gone to all this trouble of creating her dream man. “But if I do, you have to reward me with kisses and sexual delights. I’ve done the calculations. By showing up at the party and outing yourself as forbidden fruit,” she informed the hallucination, “you deprived me of at least twenty-seven orgasms. I figured that’s how many I’d have gotten before the heat ran its course.”

The figure froze for a second, then he shook his head as if clearing his ears of static.

He looked like a walking arsenal, with an automatic weapon slung across his shoulder, pistols at both hips and a slew of scary-looking devices on his utility belt. He wore a white snow-camo jacket and hood with a cloth mask covering the lower half of his face. All she could see were his eyes. They were the same vivid blue she remembered, then they grew distant again. Assessing, constantly shifting around the room, and almost as cold as the snow outside.

“Twenty-seven, hmm?” He stepped over to the door, his moves slick and silent. He pressed an ear against the wall, checked some gadget in his hand, then gave her a commanding wave of his hand as if ordering her to stand.

“Tell you what, let’s get the hell out of here, and then we can talk about payback on those orgasms.”

“Payback is double,” she decided then and there. Why not. It was her fantasy after all.

For a brief second, she saw amusement flash in those bright eyes. For that instant, she felt the same connection that’d zinged between her and the real Blake Landon almost a year ago. Her heart sang with joy, so sure it’d found its perfect match.

Silly heart.

Then he shifted, shrugging a pack off his back. He dug into it, pulling out things even more tempting than fifty-four screaming orgasms.

Warm clothes. Thick socks, heavy boots and a coat.

She moaned. A heavy coat, with a furry hood.

This fantasy just kept getting better and better.

A cold wind whipped through the room. Ice showered her back and freezing snowflakes flecked her hair and face.

Slowly, terrified if she moved too fast he’d disappear, Alexia raised her head off her arms.

He was still there.

She blinked.

He held out the socks and boots.

Wetting her lips, she hesitated. Then, having to know one way or the other, she reached out. The wool socks were like fire, hot and welcoming.

The boots waggled. Her gaze flew from the sturdy cold-weather footwear to the man’s face. He was real? He was here to rescue her?

Alexia’s mind couldn’t seem to take it in.

Thankfully, though, her body was all over the idea, grabbing the socks and yanking them over her frozen toes.

“You’re real?” she whispered, reaching out for the boots.

“As real as you are, sweetheart. Let’s get our asses in gear. We have five minutes before this place is blown to hell.”

She should be scared, shouldn’t she?

Or relieved?

Excited or ecstatic or grateful.

Maybe the weather had frozen her emotions, too, because she couldn’t feel a thing.

Except the cold.

Like moving through a dream, Alexia snuggled herself into the warmth of the white camouflage winter gear. Her brain was foggy as she tried to accept that Blake was real. The possibility that he was a figment of her desperate imagination didn’t stop her from following him to the window, though.

Her movements were stiff as she took his hand to help her climb onto the chair, wishing she could feel him through their thick gloves, her body feeling as if she’d just recovered from a vile flu.

He was real.

He was here.

She was rescued.

“Is there a team outside?” she asked. As much as she wanted out of this room, she knew there was an arsenal pointed at the window, armed guards who’d be thrilled to use her for target practice and a seriously strong chance that she’d break a leg crawling out a second-story window.

“We’re on our own,” he said quietly, stepping up to the window, too, and using his infrared binoculars to check the landscape. “There’s a rope hanging just outside the ledge. Do you see it?”

“On our own?”

How was that possible? SEALs operated in teams.

Suddenly her brain sparked to life. Like a limb waking, the tingles were painful as she tried to figure out what was going on.

“Where’s the rest of the team? Your backup?” It was unfortunate that her words came out shrill with an overtone of hysteria. But, well, she was pretty close to hysterical, so it was only to be expected.

“We’re the team, you and I. We’re not going to need backup because nobody’s going to be paying us any attention in—” he glanced at his watch again “—four minutes.”

He wasn’t hysterical. She frowned, peering at his face to try to see if his mellow certainty was an act or if he was really okay with being a one-man rescue show.

The more she looked, the calmer she became. As if she was absorbing his confidence and strength. Granted, he was almost completely shrouded in warm winter gear. But his voice, his stance, his entire persona were one hundred percent assured. He was trained for this, she told herself. He’d done hundreds, maybe thousands, of missions in much riskier situations. He’d served during wartime, for crying out loud.

But that was him.

She was pretty much a wimp.

“We’re really on our own?” she whispered. Then, with a shaky breath, she glanced at the rickety desk and sad stool. Maybe she should stay here.

“Do you trust me?”

Her gaze flew to his face. Covered in goggles, surrounded by a cinched hood, she could barely make out his features.

“Do you trust me?” he repeated.

Her heart sighed, even as terror clutched her guts. They’d have to sneak through a terrorist encampment filled with gleeful murderers to hide in a vicious snowstorm. Just the two of them, with no backup. No access to help. Nobody to rescue them if something went wrong.

Of course, if they stayed here, they’d be blown to bits in four minutes.

Alexia wet her parched lips, then nodded.

“I trust you.”

Blake moved closer. He took her right hand, so warm now inside its heated glove, and tucked it up inside the wristband of her coat. Then he did the same with the left.

Alexia’s body came awake much faster than her mind had. Warmth, not felt since the last time he touched her, slid through her body. Like liquid pleasure, it permeated, slowly trickling all the way to her toes.

He tugged on the zipper of her coat, snugging it up to just below her throat, then with hands so gentle she almost wept, he smoothed her hair away from her face and lifted the hood of the coat. The fabric was so thick, so warm. When he pulled the strings closed to cinch it tight around her face, she felt as if she was in a sound tunnel, the beat of her heart amplified in her ears.

He let go for just a second to reach into the pack and pull out a pair of goggle-like glasses, sliding them onto her nose. Then he tugged the zipper higher, snapping the front of the jacket tight so not a whisper of cold air could touch anything but the little bits of her face still exposed.

Alexia wasn’t sure she’d ever felt so protected. So cared for.

“Do whatever I tell you,” he said softly, his gaze intense as he stared into her eyes. “Stay low, follow in my exact steps. I’ll get you home safe and sound. I promise.”

Unable to believe otherwise when he was looking at her like this, she nodded.

“I need you to really trust me, Alexia. Not because I’m the lesser of two evils, but because you have complete faith that I’ll keep you safe. That I know exactly what I’m doing, that I’m damn good at it and that you know without a doubt that I’m going to get you out of here.”

The huge lump in her throat made it hard to swallow, so Alexia just nodded instead of speaking.

“You’re sure?”

She took a deep breath, then swallowed again. “I trust you, completely,” she promised breathlessly.

His smile was like the rising sun. Warm, vivid and beautiful. She melted. Then, his hands still on the zipper of her jacket, he tugged her closer. Bent his head and kissed her.

Oh, baby.

His lips were as soft, as delicious, as magical as she’d remembered. The kiss was short, way too short, but so sweet she would have cried if she wasn’t afraid the tears would freeze on her face.

He slowly pulled back, his eyes still locked on hers. Then he flicked a button in the side of the goggles, activating a buzzing in her ears. Communication device, she realized.

“What’s that for?” she whispered, her breath an icy mist between them. “Luck?”

“I don’t need luck, sweetheart. I’m the best. That’s why I was handpicked to rescue you. That—” he kissed her again, just a quick brush of his chilly lips against hers “—that was because I’ve missed you.”

Nothing like fogging a woman’s brain and sending her heart into a nosedive of delight to get her to climb out a tiny window into an enemy-filled snow-hell.

She didn’t know if she should admit she’d missed him or not. If she did, it’d be like a deathbed confession, said because she knew she’d never have another chance. Call her superstitious, but she’d rather wait to make any emotional declarations until they were safe.

“Lucky me,” she said instead, putting all the things she couldn’t say into her smile and hoping he understood. “I’m glad I rate the best.”

* * *

BLAKE WISHED she hadn’t smiled.

It touched something inside him, ratcheted the stakes so much higher.

He was here to do a job, and he couldn’t do that job if he let emotions in. Any kind of emotions. The key to a successful mission was a clear mind, the ability to think three steps ahead and a solid handle on the outcome, while keeping a fluid sense of the steps in between.

He’d learned early in his career that the only way to succeed was to shut out fear. Worrying, in any form, was the equivalent of strapping a bull’s-eye on his back.

He shouldn’t have kissed her.

He was on a mission.

She was his mission.

Kissing the rescue target was totally against protocol.

He hadn’t been able to resist.

Blake hefted his pack onto his shoulders again, then checked the time.

Two minutes.

“Let’s go.”

He made sure she was situated on the chair, then grabbed the windowsill and pulled himself up. He glanced at her again.

“Promise. You do exactly what I say.”

“Promise.”

“Even if I say run, without me, you’ll do it. The coordinates, a compass and a GPS are in your jacket. Don’t take it off.”

Her eyes were huge behind the protective lenses. Her nod was a jerk of her chin. But her lips were pressed in a determined line, and if her hands were shaking inside her gloves, the tremor was mild.

She’d hold up.

Blake glanced at the compound again, then reached down to pull the cloth, embedded with a tiny communication wire, across her lower face. Then he did the same to his own.

“Ready?” he whispered.

She gave a tiny start, indicating that she’d heard him through her headphones, and nodded again.

“Then let’s rock.”

He flipped the switch on his lenses, triggering the heat sensors. Two guards on the east side, one on the west. He glanced at his watch.

One minute.

One hand holding his weapon, Blake shimmied through the window, gripping the stones surrounding it and pulling himself free. He reached in to aid Alexia, but she’d already grabbed ahold of the sill and had herself halfway out. He took her hand, pulling her up so her toes were balanced on the sill and the rest of her against the stone wall, then bent low to snag the rope.

“Wait until I’m down, then follow,” he said quietly.

Her gaze ricocheted around the compound as if she was watching for the devil to come riding in. But she nodded. Using the rope, his back to the wall so he could watch for threats, he quickly lowered himself to the ground. He sank into the snow to midcalf.

It only took him a second to reach into the small white pack he’d stashed at the base of the wall and pull out the snowshoes. Fully alert, his finger still on the trigger of his revolver, he swiftly stepped into them.

“Go,” he told Alexia.

She flew down the wall. He winced twice as her body bounced off the stones, but she didn’t slow. Clearly she wanted the hell out of here.

He liked giving a lady what she wanted.

“Put these on,” he told her as soon as she’d released the rope. She squinted at the snowshoes, then nodded. He made sure she knew what she was doing as she put the first one on. He glanced at his watch as she finished the second.

One minute past. The explosion should have already happened, providing cover for their escape. He scanned the guards again. Still in place.

Recalling one of Phil’s favorite sayings, no worries, no bull’s-eyes, he reached into his boot and pulled out his backup Glock.

“Ready?” he asked Alexia, giving her a once-over.

“Ready.”

He handed her the gun.

Her gasp echoed in his ears. But she took it. With a sureness that’d do the admiral proud, she checked the clip, the safety. Her breath just as loud in his speaker again, she nodded.

What a woman.

Grinning behind his mask, Blake tilted his head to the north. Time to go.

As soon as he stepped a foot from the building, he was buffeted by driving snow.

“Hold on to my belt,” he instructed.

A second later he felt the pressure of her fingers. Good. Now he could focus ahead without needing to check her progress.

Without the wind and snow, they could have made the hundred and fifty yards to the fence line in less than half a minute. But running at a crouch through a foot of snow took twice that.

When they reached the bare expanse of wire fence, he stooped. Alexia did the same. Watching constantly, he pulled out what looked like a pair of tiny rubber pincers. He’d come in overhead, rappelling from the trees to the top of the building. To leave, they needed to cut the barbed wire.

He hesitated. As soon as he clamped the wires, an alarm would sound. If the compound had already been hit, the chaos would have covered their escape.

This, or the gates, were the only way out. Orders were to stay covert and not to engage the enemy.

So they’d stick with the plan. And run a little faster.

He took a deep breath.

Then, knowing what was likely to come, he looked at Alexia. Her brown eyes were huge, her lips white. Still, she gave him a reassuring smile.

“So far so good,” she whispered.

He nodded.

“As soon as I cut this, we’re tagged. There’s a vehicle waiting a mile to the east. In it is a radio in case you have to communicate with anyone.” He hesitated, then decided she was strong enough—had to be strong enough—to face reality. “If we’re engaged, you keep running. Don’t wait for me. Don’t look back or try to help. Head for the vehicle, get the hell out of here.”