По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

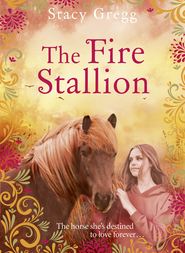

The Island of Lost Horses

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“It died,” I said. And the thought briefly flashed into my mind, should I tell Mom what had happened to me? No. I stopped myself.

If she knows what happened then she won’t let you go back there – and you must go back. You have to see your horse again…

“Mom?” I took a deep breath. “Can we go back to the boat, please? I think I’m going to throw up…”

I managed to control the nausea, even with the Zodiac bouncing and skittering across the waves. I sat in the prow on the bench seat, focusing hard on the horizon, which is what you do to stop feeling seasick.

When we reached the Phaedra, Mom tied off the inflatable while I dragged myself up the ladder and on to the deck. I was still a bit shaky and I stumbled and fell forward, grabbing the side of the boat to stay upright.

“Are you sure you don’t need a doctor?” Mom asked. It was a silly question. Even if I did need a doctor where would we find one in a wilderness reserve on the outer edge of the Bahamas?

“I just need to lie down,” I insisted.

“Do you want me to make you something to eat?” Mom offered.

I shook my head gently. “No thanks, Mom. I just need to sleep.”

I made my way past the steering cabin and the kitchen on the upper deck, gripping the railings the whole way, and then down the narrow stairs that led to our room.

Below deck there are two rooms. The room at the front of the boat is where the jellyfish tanks and monitors and equipment are kept. And the other room is for me and Mom. On my side the walls are covered with horse pictures. The best one is of Meredith Michaels-Beerbaum jumping her horse Shutterfly over this huge water jump at the Olympics.

I flopped down face first on my bunk mattress, my sunburn throbbing, body aching. Then I thought about the diary and I forced myself to sit up again.

I had dumped my backpack on the floor and I reached out and grasped it, dragging it closer so I could unzip it. The ancient diary was right at the top where I had packed it, bound up in filthy, grey cloth.

I noticed as I unwrapped it that the rags were trimmed with tattered lace and there was even a collar with a buttonhole. I guessed the cloth had once been an old-fashioned shirt, but it was so decayed it was hard to imagine anyone ever wearing it.

I put the cloth aside and held the diary in my hands, my fingers tracing the stiff cracks in the leather, the letters stamped on the front.

I was about to open it to the page where I had last finished reading when there were footsteps on the stairs.

“Bee?” I hurriedly wrapped the diary in its cloth and shoved it back inside the backpack. My heart was pounding. I waited a beat, expecting the door to open.

“Yeah?”

“I’m going to cook some pasta. You want some?”

“Uhh,” I hesitated, “no thanks, Mom. I’m not hungry.”

“OK.”

I waited for a heartbeat or two and then I heard her go back up the stairs. I was about to reach over and take the ancient diary out of the backpack again when a thought occurred to me.

I got up from my bunk and pulled open the drawer underneath where my books were kept. I had to dig through the pile, and for a moment I thought maybe it wasn’t even there. But here it was, right at the very bottom. It was smaller than I remembered it, with a blue cover and pale yellow lined pages. I opened my ‘Year 5’ diary and was relieved to find that, as I remembered, most of it was blank.

My handwriting hadn’t changed much over the past three years since I wrote these entries.

The diary had been a school assignment and our teacher Mrs Moskowitz graded it. We were supposed to write our feelings but I never did. Even though Mom and Dad were fighting. This was just before they broke up, before we left Florida.

I didn’t mention anything about horses either. I was worried that someone might grab the diary off me in class and read it out loud and I already got teased about being a ‘horsey girl’.

Most of the entries were about what I ate for lunch and who I sat next to in class and stuff. On the last page I had written all about how Kristen Adams and I were the bestest friends in the whole of Year 5. I winced a bit when I read that. Some BFF. She hadn’t returned my emails for at least two years.

Anyway, once I’d read that page I ripped them all out – the ones with writing on them. I tore them carefully so as not to disturb the blank pages and I balled up the used ones and tossed them aside on my bed. Then I propped myself up on my pillows and smoothed down the first clear page. It felt good to have that empty page looking back at me – waiting for me to put something on it.

I thought back to when Annie had given me Felipa’s diary. She had acted really serious about it, handing it to me like it was a big deal. “Bee-a-trizz,” she said. “You be de guardian of de words now.”

At the time I thought she meant that because Felipa’s diary was written in Spanish and so I could understand it, I should look after it. But now I realised that maybe Annie meant something more than that. She said I was the guardian of the words. So maybe my own words mattered too? After everything that had happened to me over the past two days, out on the mud flats and at Annie’s house, I finally had something important to write. I had my own story to tell.

It wouldn’t be like the old pages that I had torn away. It would be true this time, like diaries are meant to be, but it would be amazing too. And it would begin with the day that I found my horse. Running wild in the most impossible place you could imagine. Here, on this tiny island, a million miles from anywhere, on the outer edge of the Caribbean.

Great Abaco (#ulink_1621790c-d22d-569e-81b3-e62119fa98b0)

If things are going to make any sense at all then I need to backtrack a little and explain how I came to be on Great Abaco Island.

Mom and I had arrived, like we always do, in the wake of a bloom. A bloom is the name for a herd of jellyfish. That is what Mom does – she tracks jellyfish and studies their breeding patterns.

I was nine years old when Mom yanked me out of school and straight into the middle of nowhere. She’s been dragging me around on the Phaedra with her for three years now, back and forth around the islands so that a map of the Bahamas has been seared into my brain.

Jellyfish, by the way, are totally brainless. I’m not being mean just because they are taking up what should be my bedroom – it’s the truth. Mom says they cope perfectly well without a brain. She says that Nature, unlike people, is non-judgemental about such matters. But I think Nature needs to take a good hard look at itself because it has invented some really stupid stuff. Did you know that a jellyfish’s mouth and bottom is the same hole? Eughh!

Even without brains, jellies can get together and bloom, and when they do we follow them. Our boat, the Phaedra, is real pretty. She’s painted all white with her name written in swirly blue letters above the waterline so that it seems to dance on the waves.

The Phaedra was designed as a lobster trawler, so she can only do 12 knots an hour. Which is OK since the jellyfish blooms that we chase never move faster than two knots.

Some of the islands that the jellies lead us to are really small, not much more than a reef and a few trees. Others are huge with big hotels and water parks, and at Christmas time when the tourists come they turn into Disneylands.

This was the very first time we had been to Great Abaco. It’s a remote jungle island, a long way from the mainland of Nassau, and we had charted our course to arrive at the island’s marina at Marsh Harbour so we could take a mooring for the night and buy supplies and refuel.

That first evening, instead of cooking onboard in our tiny kitchen, we went ashore and Mom treated us to dinner at Wally’s. It’s the local scuba divers’ hangout: a bright pink two-storey place, run-down but in a nice way. We sat on the balcony and I had a conch burger, which I always order, and fries and key lime pie. I was halfway through my dessert, when I asked Mom about moving back to Florida.

The funny thing is, when we left Florida Mom had me totally convinced about how much fun our lives would be. It would be an adventure. I’d be skipping out on school and travelling the high seas – like a pirate or something.

Trust me – it is not like that at all.

For starters, I still do school. Only now I am a creepy home-schooler. I do correspondence classes and workbooks and talk to my tutors over the internet.

“I have no friends here,” I told Mom as I ate my pie.

When I left school everyone made this huge fuss about how much they would miss me and stay in touch. Especially Kristen, making a big show of how we would be Best Friends Forever. Forever, it turns out, was a couple of months and then the emails and Skype just stopped.

“Well maybe you need to make more of an effort,” Mom countered.

This was what she always said. But she couldn’t say it was my fault about the horses.

In Florida we had a stables just down the road. I would park up my bike there after school on the way home and feed the horses over the fence. I had been begging Mom for lessons since I was really little and right before we left she had promised I could start.

“You did,” I said. “You promised.”