По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

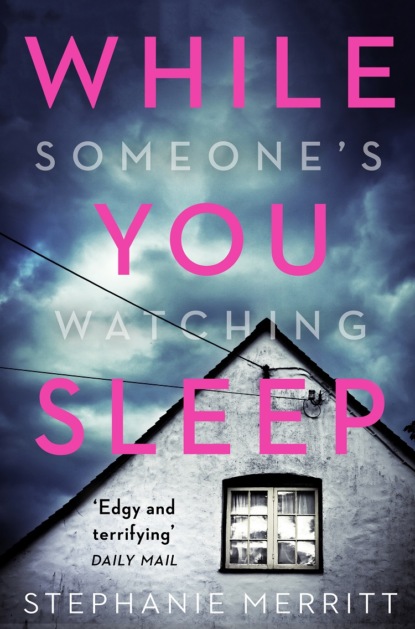

While You Sleep: A chilling, unputdownable psychological thriller that will send shivers up your spine!

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The stairs creaked as she ascended, one step at a time, pausing to listen. Again she felt that creeping cold at the back of her neck, a clenching in her bowel. Perhaps she had not been mistaken; perhaps someone had found a way into the house. She had locked the front door behind Mick, but there must be other doors and windows in a place this size; she had not checked them all before she fell asleep. But why would an intruder advertise her presence by singing? Zoe advanced as far as the landing, wishing she had thought to bring some makeshift weapon – a poker, or even an umbrella. If someone had broken in, they could be unhinged, and potentially dangerous. She glanced over the banister into the pool of darkness below, thinking of the telephone on its table in the hall; briefly she considered running back down, calling Mick and Kaye. How long would it take Mick to drive here – fifteen minutes, perhaps, twenty at the most? She stopped, took a breath, registered her own choice of words. If someone was there. She had somehow undressed herself and sleepwalked naked into the gallery; who was to say she was not still half-asleep, imagining the singing, the presence, the scratching? She could not call Mick and Kaye in the middle of the night, on her first night here, because she was hearing things and it turned out she was not as brave or self-reliant as she wanted to believe. Gripping the banister, she walked the length of the second-floor landing with a purposeful stride, her mouth set firm. The singing continued, its volume unvarying, as if the singer was oblivious to Zoe’s footsteps or the creak of the stairs. It seemed to be coming from behind a closed door at the far end. Zoe stood in front of it, hesitated, then tried the brass knob. The door was locked.

She turned it in both directions, rattled it hard, but the door refused to give, and the singing continued, unperturbed; if anything, the bleak emotion in the singer’s voice intensified. Zoe found herself arrested by the sheer force of the woman’s grief; it infected the atmosphere of the entire house, soaking through Zoe’s skin until she felt saturated with it, until she feared her heart might crack open with the weight of such fathomless loss. She mastered herself, tried the door once more. When it remained stubbornly locked, she knocked on it, hard, with her knuckles.

‘Who’s there?’ she called, tentatively at first, then bolder. ‘Who are you? Come out.’

No one answered, though she thought the voice seemed to grow a little fainter. She knocked again, shook the doorknob, and the next time she called, the song faded gradually away, like a track on an old record, leaving only an expectant silence. The landing settled into stillness. Zoe pulled the blanket tighter around her and leaned against the door, felled by exhaustion. There was no one here; she felt unaccountably angry with herself for her own weakness. As she turned towards the stairs, she sensed a draught on the back of her neck and, in her ear, a breathy sound that might have been laughter, or a sob.

When she woke, it was past eleven and sunlight streamed through a gap in the curtains. She was lying in bed, naked, the woollen blanket she had pulled from the couch in the gallery bundled under the cover beside her. So she had not dreamed that part, at least. She sat up, hugging her knees to her chest, squinting into the light. After the whisky, the jet lag and the disturbed night, she had expected a jagged-edged hangover, but as she uncurled her fingers and stretched her arms out, rolling her shoulders, she could detect no trace of a headache. Instead she felt unusually light and invigorated. She swung her legs over the bed and the sight of them – long, lean, pale – brought back a flash of images from the night before. That dream – she flushed at the memory of it, squeezing her thighs together. She used to have intensely vivid sex dreams when she was younger, but they had retreated into the background somewhere along the way, like the rest of her sex life. Back then, though, the lovers who featured in her dreams were variations on men she knew, often men she had never knowingly entertained any such feelings towards in her waking life. But this dream lover was different; he was unreal, perfect, formed from her own unarticulated longings. If she could, she would have fallen back on to the bed and invited the vision back, but she knew that would never happen. It was fleeting, delicious, gone. And everything that had followed – the fear, the scratching, the singing – seemed easy to explain away now: fevered imaginings of a mind torn abruptly from sleep and confused by dreams. Thank God she had not called Mick and Kaye with her wild night-terrors; how ridiculous she would have looked. She curled with shame at the thought.

Zoe unlocked her suitcase, dug out a pair of track pants, a tank and an old cashmere jumper of Dan’s, and padded down to find the kitchen. It was a large, wide room at the back of the house, facing the shore, with a door that led out to the veranda; a proper old farmhouse kitchen, tastefully modernised, with a stone floor and walls painted in a muted slate-blue and cream. She opened and closed a few wooden cupboards. All the appliances and cookware were branded, the kind of names that would meet with the approval of the well-heeled guests they obviously hoped to attract. Zoe filled the kettle, found a cafetière and an unopened packet of filter coffee and considered again, while it was brewing, how strange it was that Mick and Kaye should have gone to so much trouble and expense to restore this house so beautifully and leave it to strangers, while they went on living above the pub. A five-mile drive to work would be nothing, for the joy of waking up to this view every morning. Perhaps they were counting on the income as an investment; she supposed the pub trade must suffer out of season. Perhaps – and she pushed this thought to a corner of her mind – they did not want to risk being cut off in winter.

The kitchen door was firmly locked and bolted from the inside, the keys hanging on a hook behind it, as Mick had said. All the windows were closed and secured, she noticed, with window locks; there was no chance that anyone could really have entered the house last night. Tired brain, she reproached herself, sliding back the bolts. She poured her coffee into a large pottery mug and stepped outside with it into a warm wash of golden, late-autumn sunshine. The boards of the veranda felt damp under her bare feet and though the air carried the sharp, clean edge of October, the light was gentle, caressing her face. She wrapped her hands around the steaming mug and took in her new home for the first time.

The sea had retreated, leaving a corrugated expanse of tawny sand, scattered with pebbles and ribbons of kelp. The wind of the previous night had dropped and in the curve of her little bay the water shone like mercury under the light, calm now and docile, lapping in slow rhythmic waves at the shore. Above it, scalloped rows of white clouds drifted across an expanse of blue, rinsed clean and bright. Seabirds wheeled overhead, banking sharply or floating on invisible streams, complaining to one another. Zoe walked to the end of the veranda, to the corner where it joined the north side of the house, and tilted her face to the sun, breathing in salt, damp earth, fresh coffee as she absorbed the colours of the bay – violet and gold, azure, emerald and indigo – picturing how she would mix those colours in her palette, how thickly they could be layered to recreate the textures of sea, rock, cloud. She sensed the old quickening in her gut at the prospect of creating something from nothing, the days stretching ahead, blank canvases, no demands on her except the paintings themselves, their own forms. Was this freedom, then? Was this it – the freedom she had secretly craved over the past decade: no husband, no child, only herself alone with an empty canvas and a view of the wild sea? She allowed her gaze to sweep around the deserted beach. The answer, of course, was no. This was not true freedom, not the freedom of her youth, because implicit in their absence was her own dereliction – of her responsibilities, of the ties that should have anchored her. There could be no freedom now that was not tainted with guilt.

‘I hope you find what you’re looking for.’ The last words Dan had said to her before she left, in a voice tight with anger, making clear that nothing she might gain from this decision would ever outweigh the price she was asking everyone else to pay. Leaning against the wall in the hallway, arms folded across his chest, as the cab driver rang the buzzer. Watching as she tried to wrestle her cases down the stairs, not offering to help, in case she should mistake that for approval or acquiescence; determined to the very end that she should not imagine, even for a second, that she had his blessing.

‘The fuck?’ he had said, the night she had announced her project over dinner. So she had repeated it, clearly, patiently, but he had continued to stare at her, knife and fork poised in mid-air.

‘So you went ahead and planned all this without even asking me?’ he said, when he had eventually processed it.

‘Like you went ahead and decided to quit your job without discussing it,’ she replied, evenly.

‘What – you can’t even compare—’ He put the cutlery down, ran both hands through his hair, clutching at clumps of it. ‘There was nothing to discuss – it was a good offer. Better than I expected. Architects are the first to suffer in a downturn, you know that. The whole construction industry’s feeling it. Guys are being laid off all over. I had to take that deal before I was left with no choice. I did it so I could be around for you more. It was the opposite of fucking running away.’

Zoe said nothing; it was easier to let Dan go on believing himself to be right. How could she explain it to him? The last decade had not diminished him, as it had her. He had not had to give up his place in the world since becoming a parent; he still put on a good suit and set out to work every day, solved problems, engaged his intellect, kept his skills sharp. He spent several evenings a week dining with clients and associates, occasionally taking her along when they could find a sitter, but mostly not; he continued to travel frequently for contracts and conferences, sometimes to Europe, more often across the country to consult on projects with the Seattle office. She had not failed to notice that meetings were often arranged there for Monday mornings, obliging him to stay the weekend; she had noticed too that his first point of contact in Seattle was a colleague called Lauren Carrera, a woman who appeared to have no concept of time zones and would call him on his cell with supposedly urgent queries long past midnight, calls he would retreat downstairs to take in his office, his voice soft and light, full of easy laughter, the way she had not heard it in a long time. Lauren Carrera was in her early thirties and too exhibitionist to set her Facebook photos to private; in all of them she was skiing or surfing or running half-marathons for charity, or raising tequila shots with a vast and diverse group of friends. Zoe had never asked Dan outright if he had slept with Lauren Carrera, because he was no good at lying and she didn’t want to have to watch him try.

Dan’s life was compartmentalised, in the way that was permitted to men; home, fatherhood, was only a part of it. It had always been assumed that she would stay home once Caleb was born, and she had felt in no position to argue; it was not as if she earned enough from her paintings to support a family – though one day she might have done, if she had been allowed to try. She would never know now, what her early promise might have flowered into. ‘You can always paint while the baby’s asleep,’ Dan had said cheerfully, knotting his tie in the mirror after five brief days of paternity leave, unwittingly revealing with those few words how he regarded her work. A small chip of ice had embedded itself in the heart of their marriage, though as usual she had said nothing. For the best part of a decade she had been disappearing, her life shrunk to a cycle of bake sales and swim team practice, as the ice spread slowly outwards from the centre. In recent years she had found herself growing panicky, all her thoughts swarming relentlessly back to the same, unanswered question: Is this it? In her darkest moments, she sometimes wondered if she was now being punished for her ingratitude, her inability to be content.

‘How will this help?’ Dan had persisted, the night she had told him about the island. ‘I’ve said over and over we should go back to counselling, but you just want to run away from everything, like some adolescent?’

‘We tried counselling. It didn’t work.’

‘It’s not fucking magic.’ He pulled at his hair. ‘You have to stick at it. Jesus, Zo …’ The anger subsided into weary despair: ‘We can’t go on like this. You know that.’

‘I need some time by myself.’

‘That’s not how marriage works. You don’t get to take a break for a bit when it gets difficult – you do it together. That’s what I always believed, anyway. What does Dr Schlesinger have to say about your big plan, huh?’

She didn’t tell him that she had stopped seeing Dr Schlesinger weeks ago; the suggestion that she was expected to seek permission for her decisions needled her.

‘It’s only a month,’ she had replied instead, surprised by how calm she sounded. ‘I’ll be back before Thanksgiving.’ It was easier to let him believe that too.

He changed tack. ‘How are you paying for this?’

‘I saved.’

‘Oh, you saved?’ He cocked an eyebrow. She didn’t respond. All the implications contained in that question that was not a question at all but an accusation. What’s mine is yours, and what’s yours is yours, is that it? But her income, such as it was – from two days a week teaching art at a Catholic girls’ middle school – was always supposed to be for her alone, that was what they had agreed, for the little luxuries that she would not have dreamed of taking from the household budget. Clothes, perfume, occasional nights out with her girlfriends. But she had had no social life for the best part of a year, much less bought new clothes. Unsurprisingly, Dan had failed to notice that.

‘And what about us?’ he had asked quietly. ‘What about …?’ and pointed up at the ceiling, meaning Caleb’s room, saving the lowest blow for last.

At that point she had raised her hand, enough, and stood up from the table, walked out of the house.

Now, with this unfamiliar sea stretching before her, she smiled into the sunlight, forcing herself to shake off her guilt. It had been Dan’s choice to take voluntary redundancy, a choice he had not thought to discuss with her before presenting it as a fait accompli, but in it she found an opportunity; she could not have imagined herself leaving otherwise. It would be good for him to spend some time at home, to think of Caleb first for once. They could not have continued as they were; on that, at least, they agreed. Draining the last of her coffee, she set the mug on the veranda and padded down the wooden stairs – eight of them – on to the beach. The chill of the sand between her toes made her gasp; she had to step gingerly over the bands of shingle, until she reached the lacy patterns of foam where the waves petered out and receded. The water touched her feet, cold as a blade.

She walked along the shore as far as the outcrop of rocks at the south end of the bay’s crescent and looked back at the house, squinting into the sun, shielding her eyes to take in its silhouette. In the morning light it looked benign, its crooked gables, ecclesiastical windows and roof turret charming and eccentric. Where she was standing now – this was where she had thought she glimpsed a figure on the beach, after she woke from her unexpected dream and her sleepwalking. The sand was smooth and undisturbed in this sheltered corner, where the sea did not reach. Not a trace of a footprint that wasn’t her own, except the pointed tracks of the gulls. Of course there wasn’t.

It was only later, when she showered, hot water needling her newly sensitised skin, that she happened to glance down and notice a small reddish-purple bruise on the side of her left breast, by her armpit. Probably where the strap of her bag had rubbed in all the hefting of luggage yesterday, she thought. But when she examined the bruise more closely in the mirror, it looked almost as if it bore the faint impression of teethmarks.

3 (#ub5e9202d-7191-5822-bded-edca3cf7cbc1)

Zoe had installed herself outside on the veranda, leaning back on the bench with her legs stretched out, bare feet braced against the wooden balustrade and a sketchbook in her lap, when Mick arrived at noon. She heard the growl of the Land Rover and the scattering of gravel in the drive. After a few moments, he made his way around the side of the house, calling brightly so as not to alarm her, and approached the veranda from the beach. His expression was hesitant at first, anxious even, but it softened into relief to see her so apparently at ease.

‘I see you’re straight to work.’ He shielded his eyes to look up at her as he climbed the steps.

‘Couldn’t miss this light.’ She waved her sketchbook and grinned, surprised by her own jauntiness. The sensuality of the previous night’s dream seemed to have left her lit up, more awake, more aware of her own body and her physical presence: the damp wood against the soles of her feet, the play of the wind on her face, the pencil’s precise weight and balance between her fingers. She felt unusually vivid.

‘And you slept all right?’ Mick seemed caught off guard by her good humour, as if it was not what he had expected to find and was not quite convinced by it.

‘Like a log, thanks.’ She felt the colour flare up in her cheeks.

He looked at her, pulling on his earlobe as if he was on the point of asking another question, but after a hesitation he smiled and breathed out. ‘Well, that’s great. It’s nice and quiet, at least – apart from the wind.’

‘And the sea,’ she said, laughing. ‘And the gulls, and the seals.’ She stopped, abruptly. She had almost said, ‘and the singing.’

‘True. But you’ll get used to those in time, I hope. Can I interrupt you for a quick tour of the boring stuff?’

He showed her how to change the timer for the heating and hot water, the outbuilding at the front of the house where he had stacked chopped wood for the kitchen range, the fuse box under the stairs and the cellar with the generator that would, in theory, run the electricity in the event of a power cut. She wasn’t wholly paying attention to the instructions; the cellar had a dank, forbidding atmosphere and a musty smell that made her want to get out as quickly as possible, and she was alarmed by the thought of being stuck out here with no power.

‘You’ll be fine, don’t worry,’ Mick said, catching her expression as he demonstrated how to light the hurricane lamps. ‘It’s just that it’s all very new out here – there was no mains electricity or running water when we started doing up the house, it all had to be put in from scratch. The pipes make a bit of a racket too, I’m afraid, you probably noticed – banging and what have you. Everything’s settling in and we don’t know how it will fare in the winter storms.’

‘So I could be stuck here with no lights?’ She heard the catch in her voice as she pictured herself alone in the house with only a candle. A sharp memory of that pale singing jolted through her and she shivered, despite the sun.

‘No, no – that’s why we’ve put in the generator. Don’t fret – you won’t be left sitting out here in the dark.’ He laughed, a touch too loudly. ‘Well, then. If you’re ready, I can drop you into town for the shops and bring you back before I have to get to the pub.’

‘Oh – what about that door that’s locked upstairs?’ Zoe asked, as they returned to the kitchen.

Mick frowned. ‘What door?’

‘On the top landing. Right at the end.’

‘The turret room, you mean? Have you no had a look up there? Lovely views all across the headland. On a clear day, you can see right across to—’

‘But I don’t have the key.’

‘There is no key.’ The crease in his brow deepened. ‘None of the rooms are locked.’ He looked at her as if trying to work out whether she was having him on. ‘Maybe the handle’s stiff. Shall I take a wee look?’

‘Don’t worry if it’s—’ she began, but he was already in the hall, bounding towards the stairs, telling her it was no trouble. She followed him up two flights, conscious of a flutter of apprehension in her stomach as they approached the closed door at the end of the second-floor landing.