По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

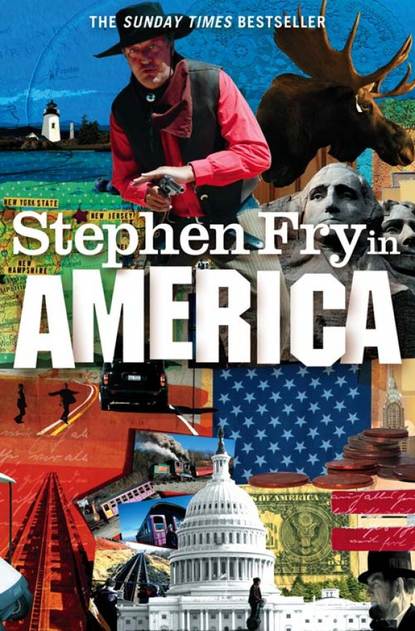

Stephen Fry in America

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Take your own cheese.

SF – June 2008

NEW ENGLAND AND THE EAST COAST (#ulink_369dc6fe-6b05-5541-9304-369b6a776ce5)

MAINE (#ulink_bf962ac0-9584-5732-b2de-7eff2e3d9bf3)

KEY FACTS

Abbreviation:

ME

Nickname:

The Pine Tree State

Capital:

Augusta

Flower:

White pinecone

Tree:

Eastern white pine

Bird:

Black-capped chickadee

Motto:

Dirigo (‘I lead’)

Well-known residents and natives:

Edward Muskie, Dorothea Dix, Winslow Homer, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow, Harriet Beecher Stowe, Edna St Vincent Millay, Artemis Ward, E.B. White, Stephen King, John Ford, Patrick Dempsey, Jonathan Frakes, Liv Tyler, Judd Nelson.

MAINE

‘I can assure you of this. If I find a friendlier, more welcoming and kinder set of people in all America than Mainers I will send you film of me eating my hat.’

Squeezed by Canada on two sides and connected to the rest of America by a straight-line border with New Hampshire, Maine is home to a million and a quarter citizens who roam roomily around a land larger than all of Scotland.

The southeast half of the state is where the urban action is. Portland and Bangor are the big towns; the former is the birthplace and home town of Stephen King, the novel laureate of Maine, whose prolific output has stayed loyal to the state for over thirty years. But I’m heading north, passing through Portland, Augusta and Bangor, getting used to how much of a head-turner my little London taxi will be. Augusta, with one of the lowest populations of any of the fifty state capitals, seems small, depressed and depressing. I hurry through on my way Down East. ‘Down’, in Maine-speak, means ‘Up’.

With the exception of Louisiana and Alaska whose administrative districts are called parishes and boroughs respectively, all the American states are divided into counties. These are much like their British counterparts, but with sheriffs who are real live law-enforcement officers rather than our ceremonial figureheads in silly costumes. Every US county has its chief town and administrative headquarters, known as the County Seat. The number of counties in each state will vary. Florida, for example, has 67, Nebraska 93 and Texas 254. Maine has just 16 and at the top right of this topmost, rightmost state you will find Washington County, the easternmost county in all America. My destination is Eastport, the easternmost town in that easternmost county.

Down East

The most obvious physical features of the Down East scenery are forest and ocean. But then this is true of the whole state. Mainers will tell you that if you were to straighten every wrinkle and crinkle of their coastline it would stretch out wider than the whole breadth of the United States – into three and half thousand miles of inlets, creeks, coves, bays, promontories, spits, sounds and headlands. As for the land – well, there is only ten per cent of Maine that is not forest and much of that is lake and river. Water and wood, then – water and wood everywhere.

They will also tell you that Eastport was once famed for its sardine-packing industry. ‘Fame’ is an odd thing in America. There cannot be many towns with a population of more than ten thousand that do not make some claim to it. It usually comes in the form of a burger: ‘Snucksville, NC – home of the world famous Snuckyburger’, a dish that will never have been heard of more than five miles from its originating diner. But ‘back in the day’ Eastport genuinely was famous for sardines. An industry, that, if the Eastporters are to be believed, was effectively wrecked by The Most Trusted Man In America.

The doyen of news anchors, Walter ‘and that’s the way it is’ Cronkite liked apparently to sail in the waters around Eastport and was disturbed one day to see a film of oil all over the water, staining the trim paintwork of his yacht. He made complaints. A government agency looked at the fish oil coming from the cannery and imposed regulations so strict that the economic viability of the business was compromised and the industry left Eastport for good. That at least is the story I was told as gospel by many Eastporters. Certainly the deserted shells of the old canneries still brood over the harbour awaiting their full regeneration. The body of water that dominates the harbour is Passamaquoddy Bay and the land on the other side is, confusingly, Canada. A line straight down the middle of the bay forms the border between the two countries.

Before the British, before the French, before any Europeans came to Maine there were the tribesmen, the ‘First Nations’ or Native Americans, as I expected I should have to be very careful to call them. Actually the word ‘Indian’ seems inoffensive to the tribespeople I speak to around town. The federal agency is still called The Bureau of Indian Affairs and there are Indian Creeks and Indian Roads and Indian Rivers everywhere. It is true that the word was wrongly applied to the native tribes by Columbus and his settlers who thought they had landed in India. But the word stuck, misnomer or not. Sometimes political correctness exists more in the furious minds of its enemies than in reality, which gets on with compromise and common sense without too much hysteria.

Anyway, the indigenous peoples of the Maine/New Brunswick area are the Passamaquoddy, a European mangling of their original name which meant something like ‘the people who live quite close to pollock and spear them a lot from small boats’, which may not be a snappy title for a tribe but can hardly be faulted as a piece of self-description.

My first full day in Eastport will see me on Passamaquoddy Bay, not spearing pollock, but hunting a local delicacy prized around the world.

Lobstering

The word Maine goes before the word lobster much as Florida goes before orange juice, Idaho before potato and Tennessee before Williams. Three out of four lobsters eaten in America, so I am told, are caught in Maine waters. There are crab, and scallop and innumerable other molluscs and crustaceans making a living in the cold Atlantic waters, but the real prize has always been lobster.

Angus McPhail has been lobstering all his life. He and his sons Charlie and Jesse agree to take me on board for a morning. ‘So long as I do my share of work.’ Hum. Work, eh? I’m in television …

‘You come aboard, you work. You can help empty and bait the pots.’

The pots are actually traps: crates filled with a tempting bag of stinky bait (for lobsters are aggressive predators of the deep and will not be lured by bright colours or attractively arranged slices of tropical fruit) that have a cunning arrangement of interior hinged doors designed to imprison any lobster that strays in. These cages are laid down in long connected lines on the American side of the border. Angus, skippering the boat, has all the latest sat nav technology to allow him to mark with an X on his screen exactly where the lures have been set. To help the boys on the deck, a buoy marked with the name of the vessel floats on the surface above each pot. Americans, as you may know, pronounce ‘buoy’ to rhyme not with ‘joy’ but with ‘hooey’.

How is it that work clothes know when they are being worn by an amateur, a dilettante, an interloper? I wear exactly the same aprons and boots and gloves as Charlie and Jesse. They look like fishermen, I look like ten types of gormless arse. Heigh ho. I had better get used to this ineluctable fact, for it will chase me across America.

It is extraordinarily hard work. The moment we reach a trap, the boys are hooking the line and hauling in the pot. In the meantime I have been stuffing the bait nets with hideously rotted fish which I am told are in fact sardines. The pot arrives on deck and instantly I must pull the lobsters from each trap and drop them on the great sorting table that forms much of the forward part of the deck. If there are good-looking crabs in the traps they can join the party too, less appetising specimens and species are thrown back into the ocean.

Lobsters of course, are mean, aggressive animals. But who can blame them for wanting a piece of my hand? They are fighting for their lives. Equipped with homegrown cutlery expressly designed to snip off bits of enemy, they don’t take my handling without a fight.

As soon as the trap has been emptied I’m at the table, sorting. This sorting is important. Livelihoods are at stake. The Maine lobstermen and marine authorities are determined not to allow over-fishing to deplete their waters and there is fierce legislation in place to protect the stocks. Jesse explains.

‘If it’s too small, it goes back in. Use this to measure.’

He hands me a complicated doodad that is something between a calibrated nutcracker and an adjustable spanner.

‘Any undersized lobsters they gotta go back in the water, okay?’

‘Don’t they taste as good?’

A look somewhere between pity and contempt meets this idiotic remark. ‘They won’t be full-grown, see? Gotta let them breed first. Keep the stocks up.’

‘Oh, yes. Of course. Duh! Sorreee!’ I always feel a fool when in the company of people who work for a living. It brings out my startling lack of common sense.

‘If you find a female in egg, notch her tail with these pliers and throw her back in too.’

‘In egg? How do I …?’

Другие аудиокниги автора Stephen Fry

Mythos

0

0