По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

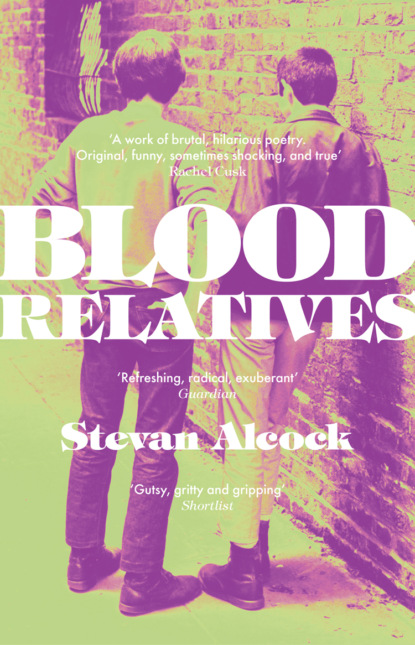

Blood Relatives

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘Oh, sorry, I wor just …’

I flushed furiously. Jim beamed his easy smile and sat beside me. He took a sip from his tea and set it down on t’ flecked brown-and-orange rug. We stared straight ahead like an old couple on a park bench. I caught t’ strong whiff of his aftershave, which he must have splashed on for my benefit while he wor out in t’ kitchen. A woman passed by t’ bay window, a blur of raincoat and headscarf, a brief shadow across t’ room.

‘Ta for t’ tea.’

‘You’re most welcome.’

Silence mushroomed. I wor missing Doctor Who. I’d be late for dinner.

I picked up my tea, took a sip, put it down, picked it up again, sipped, set it down. I feigned interest in t’ row of scraggy paperbacks propped between two wooden bookends: Valley of the Dolls, In Youth is Pleasure, Myra Breckinridge.

‘I can’t stay long,’ I murmured, my head still cocked toward t’ book titles.

I felt a hand settle on my leg, as if it had fluttered down to rest. Giovanni’s Room, The Persian Boy, The Plays of Tennessee Williams … my head wor being gently yet firmly turned away from t’ books by a man’s palm. My face wor too close to his to focus. I knew at once that I wor about to be kissed. I leaned toward him, allowing it, wanting it.

The kiss felt strange. The neat moustache brushed against my mouth, the lips moist, the tongue wor warm wi’ … I pulled away.

‘No sugar!’

‘Sorry?’

‘You don’t have sugar in yer tea!’

‘Sugar? Aye, I don’t. Shall I rinse out my mouth?’

I glanced uncertainly out the window.

‘Nope, it’s fine.’

‘Aye, well, if you’re sure now?’

‘Certain.’

And as if to show him that I wor, I kissed him again, a long, slow and exploratory kiss, while reaching down to place my hand on Matterhorn Man’s evident stiffy.

‘Shall we go upstairs a wee while?’

‘Upstairs?’

And so it started. The Saturday afternoons after work. The curtains drawn against t’ fading day. Lying naked on purple nylon sheets.

The name, I wor to discover, wor apt, cos the Matterhorn Man’s erect cock had a kink in it, a bit like t’ mountain itsen.

That wor also t’ summer that Granddad Frank died. Mother’s dad, not Mitch’s – his folk wor gone before I wor slapped into t’ world.

Not a week after he wor buried I wor idling in t’ hallway when through t’ gap between t’ half-open door and the doorframe I saw Mother, standing in t’ middle of t’ living room, eyes closed, arms extended. She began to rotate, slowly at first, then faster and faster, like a kid twirling in a playground, whirling and whirling round ’til she stopped suddenly and had to steady hersen against t’ dining table.

Then I heard her say: ‘What are little girls made of?’ and reply to hersen, all breathless, ‘Sugar! … and spice! … and all things … nice!’ and in my head I finished the rhyme off for her. ‘What are little boys made of? Slugs, and snails, and puppy dogs’ tails,’ and I knew she wor remembering Granddad Frank, cos he used to swing us round like that when we wor small and shout out t’ same rhyme, so I guessed he’d done it wi’ her an’ all. Only she’d had him to hersen cos they never did have another.

She slumped down onto t’ carpet, sobbing gently, so I slunk into t’ kitchen, opened the back door and banged it shut, like I wor just coming in.

Granddad Frank had died alone. Alone, under blistering arc lights, alone amongst a load of nurses and doctors, clamped to a defibrillator. He’d been cold twenty minute by t’ time we pitched up at Leeds General Infirmary. The dour nurse on reception said that someone had brought him in by car.

‘Who?’ barked Grandma Betty, stabbing the air wi’ her forefinger. ‘Who brought him in!?’ Grandma Betty had her frosty side all right, but never before had I seen her face all screwed up like a ball of paper.

‘No idea,’ the dour nurse stuttered. ‘Whoever it wor didn’t leave a name, and I wor on my break anyway.’

We plonked oursens on plastic chairs and waited. Except for Mitch, who stayed in t’ Austin Cambridge, engine idling cos he said the ignition wor faulty. It had been just fine yesterday. Mother wor clutching her handbag like it might float away. Grandma had both hands wrapped around a plastic cup of hot tea, her lips pressed tightly together.

We waited an age, watching people drift by. Sitting opposite me wor a tramp wi’ a gash on his hand. He wor mumbling and scratching his chest hairs furiously beneath his half-open shirt. He stank like a mouldy cheese. Two seats to his right sat a nervous Asian woman in a cerise sari and a brown anorak, rockin’ a bawling baby.

Grandma wor muttering under her breath, ‘I know who it wor, I know!’

When I asked who, she shook her head and blew her nose on a tissue that Mother passed to her.

After an age, an African doctor came up to us and ushered us all into a side room, where, he said in a cantering voice, it would be quieter.

Emily Jackson (#u4cd7cea9-0925-57c6-807d-028e1e6c01d6)

21/01/1976

‘Seducing a woman,’ Eric wor saying, ‘is like throwing a pot.’

It wor t’ arse end of January, and after t’ frenzy of pre-Christmas sales the soft-drinks trade had gone belly-up. We wor running light and ahead of schedule. So here we wor, parked up in Spencer Place, Chapeltown, heart of t’ red-light area, scoffing chip butties and watching rivulets of rainwater scurry down t’ windscreen. I worn’t in no hurry today. The Matterhorn Man wor up in Glasgow, visiting his sick mother. Eric held his chip butty in front of his gob, undecided about how to attack it.

‘To start wi’,’ he said, spraying breadcrumbs as he spoke, ‘it’s all shapeless, and you don’t know if owt will come of it, she wobbles unsure in your hands. Then, if you’re workin’ it right, she yields and starts to take shape, until …’

‘… You’ve made an urn?’

‘Ha, bloody ha. Listen to Eric and learn, lad. There ain’t nowt I can’t teach you about that mysterious being called womankind.’

Eric’s other favoured analogy wor t’ lightbulb and the iron. In t’ world according to Eric, a man is turned on like a lightbulb, but a woman heats up more slowly, like an iron. He said it wor his dad’s explanation of t’ birds and the bees. Lightbulbs and irons.

‘What if you’ve got two irons? Or two lightbulbs?’

Eric licked the salt off his lips and tossed the crumpled chip paper into t’ road.

‘Two lightbulbs? What kind of skewed thinking is that? You’d blow a bloody fuse, that’s what. Two bloody lightbulbs indeed. Sounds a bit peculiar, a bit daft. A bit queer, if yer ask me.’

I flushed. I’d been blowing fuses on every visit to t’ Matterhorn Man.

On my third, or maybe fourth visit, we’d lain in bed afterward listening to Velvet Underground on t’ record player. Jim wor idly stroking my head and smokin’ a ciggie when he asked me if I ever had any problem wi’ what we wor doing. I just laughed.

‘It wor Maxwell Confait,’ I said. ‘He wor t’ one.’

‘Eh?’

So I told him about how, late one evening, I wor slumped on t’ living-room rug in my pyjamas after my bath, one eye on t’ telly, t’other on t’ music paper beside me. Mother wor mulling over a competition where you had to write a slogan to win a caravan at Skegness. The late-night regional news drifted into a documentary about t’ murder of some male prostitute called Maxwell Confait.