По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

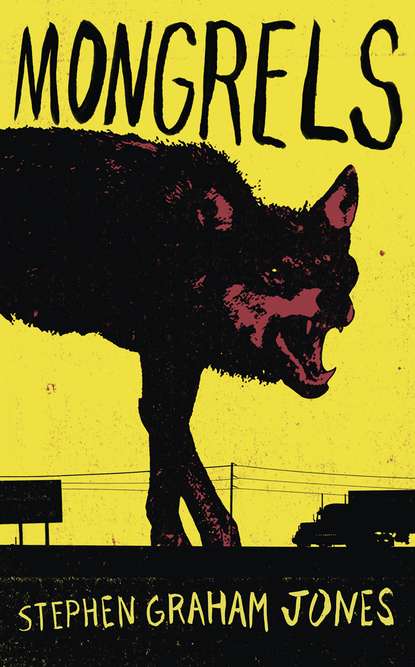

Mongrels

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“‘Libby says no,’” he repeated, mocking her thick tongue again.

If we even stole a calf away from the pastures all around us, not even a whole cow, still, ranchers would come asking, and we’d be the new tenants, the hungry tenants, the ones with big thick bones stashed in the crawlspace.

Not that a calf wouldn’t taste exactly like heaven.

Darren stood up, started peeling out of his clothes. It’s what you do when your sister can’t steal enough nickels and dimes for new pants. He kicked the back door open, arced a splattery line of pee out into the night.

“How old do you have to get for it to stop hurting?” I asked, pretending to watch the news on television. Pretending this was no big deal. Just casual conversation.

Darren rolled his head away from his right shoulder, something in there creaking and popping unnaturally loud.

Inside, he was already shifting.

“It’s worth it,” he said, then pulled the door shut so he could part the see-through curtain, make sure there was nobody hiding behind the LeSabre. Before he stepped out he looked back to me, said, “Lock that door?”

Because I didn’t have sharp teeth, or good ears. Because I couldn’t protect myself.

And then he was gone.

I rushed to the back window like every time, to try to see him halfway between man and wolf, but all I caught was a shadow slipping across the pitted dull silver of the propane tank.

Instead of ketchup, I bought a whole hot dog off the little Ferris wheel on the counter at the gas station. I pointed out which one I wanted. The old man working the register looked up to me, asked was I sure?

It’s what he did every night, like he was trying to direct me away from what was probably the oldest hot dog in the case.

I told him a different one, then a different one, and by the end of it I didn’t know if I had the oldest worst hot dog or the one that had just cycled in.

I wasn’t supposed to go out on my own, not without telling Darren or at least leaving a note—he could read that much—but there weren’t going to be any truant officers here. Libby was a werewolf, wasn’t she? Not a mother hen.

I’d thought of that one myself.

I sat on the far side of the ice machine and savored that hot dog. I’d put every condiment on it the gas station had, except mustard, and even doubled up on some, just because the old man couldn’t say anything about it. With Darren or Libby around, I’d pretend not to like this bland human food, would make a big production of wanting something with blood, something for wolves.

The hot dog was so good, though.

I scooped some relish off my pants, onto my finger, into my mouth again.

When I looked up, three kids from my grade were watching me.

“Animal boy,” the one in the red hat said, showing his own teeth.

“Don’t mess with him,” the girl of them said.

“Might catch something,” John Deere Hat agreed.

“He Mexican?” the third of them said, a boy with yellow hair. If I stood, we’d have been the exact same height.

“Still wet,” John Deere Hat said—“piso mojado, right?”—then pulled the girl along with him, heading into the gas station. Yellow Hair stood watching me.

“Piso mojado?” I said to him.

“What are you really?” he said back.

I held my hot dog out to him, not quite straightening my elbow out all the way. When he reached for it I growled like I’d heard Darren growl and lunged forward, snapping my teeth.

Yellow Hair fell back into the Nissan parked in the first slot and crabbed back onto the hood, denting it in perfectly, in a way he was definitely going to have to answer for.

I stood the rest of the way, tore another bite off my hot dog and threw the rest down, pushed past the torn-up pay phone, into the night.

Walking the fence back to our little white rent house, I kept looking behind me. Like I was hearing something. Like I was listening. Like my ears were already that good. Trick is, if somebody’s really sneaking up on you, then you’ve already made them, you know they’re there, but if you’re all alone, then spinning around every few steps, staring into the darkness, nobody’ll ever know.

Except Darren.

“Spook much, spooky?” he said from right beside me, naked as the day he was last naked. I wasn’t sure if that’s how all werewolves were, or if it was just Darren.

I didn’t even look over, just kept walking.

“I smell horseradish?” he said, crinkling his nose up.

I looked down at the commotion by his thigh. It was a big horned owl, probably three feet tall, with a wingspan twice that. A real grandfather of a bird, like from the dinosaur days of birds. It was flapping slow. Darren had bitten the feet off, it looked like, was just holding it by the bloody stumps.

Because I needed to learn, Darren let me crack the owl’s neck over when we got back to the house. It took three tries. Owls’ necks aren’t like other birds’. There’s more muscle, and they’re made to turn farther anyway. And they don’t blink the whole time you’re killing them. And the skull of a big one like that, it’s as big as your palm, like you’ve got a kid in your lap, clamped between your knees.

We sat back on the propane tank to pull the feathers out. They drifted around us, stuck in our hair, in the dead grass. It looked like a whole flock of birds had just exploded, flying over. Like they’d suicided into the propeller of a plane. Air chili.

“Owls taste any good?” I asked.

“Thought you were hungry like the wolf?” Darren said, throwing a clump of feathers at me.

Because the oven didn’t work, we cut the breast meat into long thin strips for frying. Because Darren was trying to be polite, instead of sucking them down raw like he probably would have if I wasn’t there, he breaded them up with crushed crackers, dropped them in a pan of butter. He said we could save some this way. Maybe make owl jerky with the leftovers. It would be the only owl jerky in all of Texas, probably. We could open a stand, get rich overnight.

His finger was seeping again, I could see. And he wasn’t holding the fork with that hand.

“It’s not going to heal, is it?” I said.

He didn’t answer.

Libby’d told him he knew what the cure for a silver cut was, but he’d come back that he needed both hands to drive, thanks.

The owl tasted like a thousand dead mice.

Thirty minutes after eating it, we both started throwing up fast enough that we barely made the back door in time.

“Poison,” Darren got out.

The owl had got dusted out in some field. It had eaten some house rat, its brain fizzing green with bait. It had seen Darren coming, and taken a secret-agent suicide pill.

“I’m telling—telling Libby,” I said, having to cough it out, and Darren flashed his eyes up hot at me, said some criminal I was turning out to be, then he smiled, pushed me away. I had to fall farther than he pushed to avoid my own puke. He laughed so hard it made him throw up again, and, watching him throw up, I had to throw up some more. When I could I picked up a vomited-on rock, rolled it weakly at him. He pretended to be a bowling pin, fell flat over into the grass with his eyes open like a cartoon character then rose wiping his mouth with his unbandaged hand, reached his other hand down for me just to start it all over again, and, it’s stupid, I know, but if I’d died right then from the poison, died without ever even changing, died with owl feathers stuck all over me, that would have been pretty all right.