По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

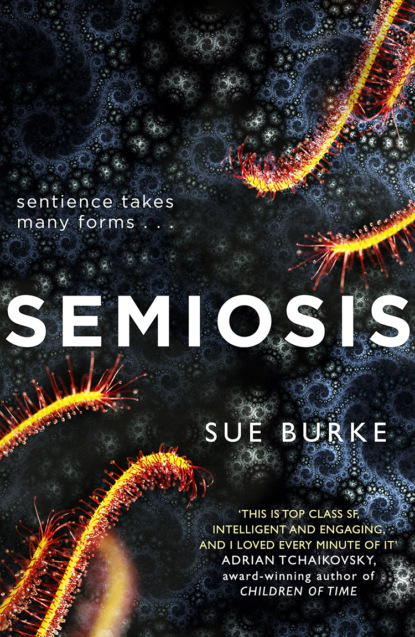

Semiosis: A novel of first contact

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Zee had carved the other markers with names and the number of days since landing. This time Merl set plain stones at each grave.

“No names or dates,” he said, brushing soil from his hands.

“We need a Pax calendar,” Vera said. “And a Pax clock.” She pointed to Lux in the western sky. “That sets three hours before the Sun, and it rises three hours before the Sun. That’s one way to measure time.”

She pointed at another starlike light, an asteroid-sized moon called Chandra.

“That orbit’s almost the same as Pax’s rotation. It’s no good for telling time, except for seasons. But Galileo,” she said, pointing to a light in the northeast, “is perfect. It goes backwards, west to east, so anyone can spot it. It orbits two and a half times a day.”

Paula squinted at the sky. “Thank you. This—”

“Now we have it,” Vera said. “We have our own way. Our own clock, our own sky, our own time. It’s what we came here for.”

With that reminder of our hopes, we returned to our daily tasks for survival. A Pax day and night lasted about twenty Earth hours, and a Pax year about 490 Earth days. A year seemed like such a long time.

A week passed, busy for both the zoologists and me. A flock of tiny moth-winged lizards arrived, flying as gracefully as a school of fish, and we watched with wonder until suddenly, as a group, they swooped down and began to bite us. Ashes and grease worked again, then suddenly the moths disappeared.

Hunting teams found half-eaten birds and fippokats and thought they saw giant birds running away, but what bothered them more were the pink slugs twenty centimeters long they found eating old carcasses. The slugs would attack anything and dissolved living flesh on contact. Grun dissected one.

“Nothing but slime. No differentiated tissue. If you chop it into twenty bits, you have twenty slugs.”

Merl discovered the source of the three-note roaring songs. “I believe I’ve found us the big-time cousin of our friends the fippokats.” He had arrived just before the evening meal and sat at a table talking calmly enough, but sweat soaked his shirt as he petted a fippokat on his lap as if to assure himself that it was docile. Everyone knew he was not an anxious man, so we listened closely.

“If I had to use one word, I’d say kangaroo, but that’s not quite it either. Giant kangaroo to use two words, a good sight taller than me, and judging from the nests they had, they can knock over trees. I believe they’re vegetarians like our friend here, root-eaters very possibly, and I’d like to believe that the claws are for digging, but they’re the size of machetes. I saw a pack of around ten of them, but I didn’t get too close. And I wouldn’t recommend getting close.”

Most colonists tended to focus their attention on animals. Merl got many more questions about his day’s finds than I did, which I tried not to let bother me, but I knew that plants with their poisons and chemicals were as dangerous as animals, and because there were so many more plants than animals, they were more important.

“The plants here aren’t like anything on Earth,” I tried to explain one night. “They have cells I can’t explain. On Earth, all seeds have one or two embryonic leaves, but here they have three or five or eight.”

“And RNA,” Grun said, “not DNA. Nothing has DNA except us.”

“But it looks the same,” Vera said.

“No,” Half-Foot Wendy said, “I mean, floating cactuses? Blue ones? But they have thorns like Earth.”

“Yes,” I said, “thorns. They need to protect themselves like Earth cacti, so they grow thorns. Plants that need to get water from soil develop roots.”

“Not like Earth,” Uri said. “No earthworms. We have sponges instead.”

“But they do the same thing,” Vera said.

“We don’t really know what they do,” I said.

“But we know what plants do,” she said. “They grow. They’re useful or they’re not. And that’s all we need to know.”

I knew we needed to know much more, and I wished Luigi Dini had survived so I would have someone to work with and to talk to.

We had already realized from the disaster on Mars that transplanting Earth ecology wouldn’t work. Crops would not grow without specific symbiotic fungi on their roots to extract nutrients, and the exact fungi would not grow without the proper soil composition, which did not exist without certain saprophytic bacteria that had proven resistant to transplantation, each life-form demanding its own billion-year-old niche. But Mars fossils and organic chemicals in interstellar comets showed that the building blocks of life were not unique to Earth. Proteins, amino acids, and carbohydrates existed everywhere. The theory of panspermia was true to a degree.

I had found a grass resembling wheat on our first day on Pax, and with a little plant tissue, a dash of hormone from buds, and some chitin, we soon had artificial seeds to plant. But would it grow? Theory was one thing and farming was another.

Then a few days before the women had died from poisoned fruit, Ramona and Carrie had seen the first shoots, and whooped and squealed until we all came to look. They were twirling around the edges of the field, hair and skirts flying, and grabbed more of us by the hands until everyone in the colony, all thirty-four of us, danced with low, slow steps at the first evidence that we might survive.

The east fruit remained plentiful—alarmingly, it became more nutritious, another mystery I should have been able to explain but could not. The west fruit rotted on the vines. Uri toiled in the fields as if he could work out his grief through his hands and his tears through irrigation water from a spring between our fields and the west vines. We had planted a second crop, a yamlike tuber, and I prayed it would remain safe to eat.

“Someday we will have to clear that west thicket for more fields,” Uri told Paula after breakfast one morning. We both heard stress tightening his voice.

“I don’t think we’ll need to clear the thicket anytime soon,” Paula said in a deliberately offhand way. We were watching the fippokats play tug-of-war with a length of bark twine in their pen. “We don’t want to do anything unnecessary until we understand the effect on the ecology. We’re the aliens here.”

“But this is necessary. The vine is a danger to us.”

“Are you still angry over Ninia’s death?” she asked, leaning back and gazing at his face.

Uri looked away. “I want peace. We all want peace.”

I kept quiet, but even if he was right, which I doubted, we could hardly eliminate such a huge thicket if we tried.

Paula leaned over the fippokat pen and dangled a stem from a leaf of Pax lettuce. The lettuce was my latest find. The leaves contained folic acid and riboflavin, among other nutrients, but the stems were too tough to eat. We had eaten a slim breakfast of lettuce, nuts, snow vine fruit, and a bit of roasted fippokat.

A fippokat hopped closer to beg for the stem. Paula shook it and the animal turned a somersault in midair. Merl had found them remarkably easy to train. She dropped the stem at its feet. “Octavo,” she said, “can you make seeds for more lettuce?”

“Of course.”

“Uri,” she said, “can you find a field for it? Have we got enough water?”

“I will fill your plate with peaceful lettuce,” he said with a toothy smile. Paula offered a sweeter smile in return, but I knew she sometimes had little patience with his antics.

Uri turned to me. “First, come look at the weeds in the wheat. One in particular has needles like nettle, so even if it is good for something, I do not want you to tell me. The thorns stick to the robot weeders and then stick to me when I clean them, and I do not have enough skin for this procedure.”

Uri pointed out a nettle growing near us. I pulled on gloves to examine the plant. Its leaves were covered with thorns like glass tubes.

“Well, thorns like this might actually have a use,” I said. I looked up. He wasn’t paying attention.

“That field!” he said, pointing toward the top of the hill. “The wheat is flat.”

He dashed up the path. I followed. From one edge almost to the other, the wheat lay flat, every little shoot, and it had stood more than halfway to my knees the day before. My wheat. Flat.

Uri reached the field before I did. He knelt to look, then pawed through the dirt. “Root rot!”

I sprinted. Root rot kills. I dropped beside Uri and brushed apart the wheat to look. Dark rot crept up the stems. I pawed through the moist soil. The roots had decayed into brown slime.

“This is our bread,” Uri howled. “Why?”

I closed my eyes and recited a textbook answer to avoid howling like him. “Disease, too much water, a nutrient shortage. A lot of things can cause it.” I stood up to look for a pattern, moving too fast and getting dizzy, but as soon as my vision cleared, I saw one. “My first guess is disease traveling via water. You can see the rot spreading downhill.”

“Can I stop it? If I stop the water?”

I could only shrug.