По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

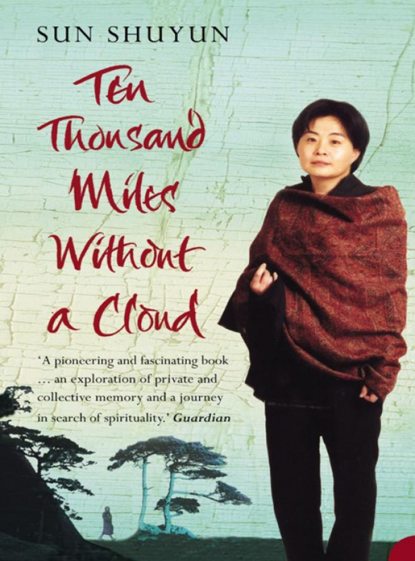

Ten Thousand Miles Without a Cloud

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

He cannot name five cereals,

His six nearest relatives he does not know …

What should we do with him?

Smash him!

I recited the poem to Grandmother one night when we were following her foot-washing ritual. She did not say anything; instead she asked me if I wanted to hear a story. I nodded for I always liked her stories; some were as magical as those in The Monkey King.

A long, long time ago, Grandmother said, a pigeon was flying about searching for food. Suddenly it saw this huge vulture hovering over it. Frightened, it began to look for a place to hide but could find none. It could see no trees, no houses, just a group of hunters on their way to the forest. In desperation, the pigeon dropped in front of a handsome prince in the hunting party, begging for protection. The vulture descended too and asked for its prey back. ‘I am hungry,’ it pleaded. ‘I have had no luck for days and if I don’t eat something, I will die of hunger. Please have pity on me too.’ The prince thought for a while and said to the vulture: ‘I cannot let you starve. Let’s weigh the pigeon. I will give you the same amount of flesh from my own body.’ His courtiers were shocked, but the prince insisted and sent one of his ministers for a set of scales. Meanwhile he had a knife sharpened. The pigeon was put in one scale, and the prince’s flesh in the other. But no matter how much of himself the prince put on the scale, the pigeon was always heavier. The vulture was so moved by the noble prince he decided not to eat the pigeon.

‘What happened to the handsome prince? Did he die of bleeding?’ I asked Grandmother impatiently, forgetting all about the poem and the clay Buddha. ‘He did not die,’ she said. ‘He was the Buddha in disguise.’ I was so relieved, and got up to take the basin of water away. Grandmother told me many stories like this. At the time I thought that was all they were, tales of animals and heroes. But she was teaching me humility, self-sacrifice, kindness, tolerance: looking back, I can see now how much she influenced me.

My father left the army in early 1966, when I was three, and the whole family moved with him from Harbin in the far north, where I was born, to Handan. It is a small city, with a history going back to the sixth century BC – the remains of the ancient citadel are still at its heart. It is most famous among the Chinese for the numerous idioms which permeate our language. Everyone knows the phrase ‘Learn to walk in Handan’ – it means if you learn something new, learn it properly, otherwise you are just a dilettante. Father said we were lucky to live in this old, civilized place.

Father was made head of production in a state timber factory employing 400 people – but there was no production. Hardly had he settled down in his new job, when the Cultural Revolution began. It was to purge the Communist Party of anyone who was not sufficiently progressive, to shake the country out of its complacency, and to revive enthusiasm for the Communist cause. The Red Guards were the front-runners but the real players were the workers. My father’s workforce was busy grabbing power from the municipal government; people fought each other, armed with guns stolen from military barracks. The city and the timber plant were divided into two factions, the United and the Alliance, with the former in control and the latter trying to oust them. My father tried to persuade the two sides to go back to work but nobody listened to him. ‘Chairman Mao says revolution first, production second. How dare you oppose our great leader?’ one of his workers warned him. Eventually, Father joined the United faction: nobody could sit on the fence or they would be targets themselves. All our neighbours were United members.

My father often told us how much he regretted leaving the army. At least we would have felt safe inside the barracks. Our new home town reminded him of a battlefield, with machine-guns, cannons and explosives going off day and night. In this escalating violence, my mother was about to give birth to her fourth child. Grandmother was happy, her face all smiles. She told Father that all the signs of the pregnancy indicated that Mother would produce a son this time: her reactions were very strong, unlike the previous three times; she insisted on vinegar and pickled cabbage with every meal; her stomach was pointed but not very big; most importantly, two pale marks like butterflies had appeared on her cheeks. My father could not conceal his delight – he did not lose his temper as often as before. He spent many months deliberating on a suitable name and in the end he chose Zhaodong, ‘Sunshine in the East’. To him, a son would be as precious as the sun – but it had a double meaning: all Chinese had been singing ‘East is Red’ in praise of the Great Leader, Chairman Mao, who was like the sun rising in the east to bring China out of darkness.

The birth was complicated. Almost all doctors had been labelled ‘Capitalist experts’ and sent to the country or to labour camps for re-education; hospitals were taken over by the Red Guards, who were more interested in saving people’s souls than their lives. The constant fighting in the streets and the blockades put up by all the factions made the journey to the hospital impossible. Mother consulted with Father and decided it would be better to use the woman from a nearby village who served as a midwife – experienced if not trained. Unfortunately the baby’s legs came out first and the midwife panicked. She asked Mother to breathe deeply and push hard. The baby reluctantly showed a bit more of itself: it was a boy indeed but there he stuck, seemingly unwilling to come into this turbulent world.

Then Mother started bleeding heavily. Father was frightened to death and kept asking Grandmother what to do. Grandmother tried to calm him down but her teeth were chattering like castanets. While Father was pacing about like a caged animal, Grandmother knelt down and began to pray loudly to Guanyin, holding tight to Mother’s hand. ‘I have been praying to you for more than fifty years,’ she pleaded urgently. ‘If you have too much to do and can only help me once, please do it now. I need you more than ever. I am begging you.’ She promised she would do anything if the boy was delivered safely: she would produce a thanksgiving banquet for Guanyin for seven days; she would go on a pilgrimage to her place of abode in southern China even if she had to pawn her bracelet, her only piece of jade; she would tell her grandchildren to remember the loving kindness of the Bodhisattva for ever. While Grandmother was praying fervently, the midwife was pulling hard, as if it did not matter if a limb was broken as long as the boy was alive. When he was finally dragged out, he had his arms above his head, looking as though he had surrendered to the world.

With the baby’s first cry, Father fell on his knees beside Grandmother, thumping the floor with his fist and murmuring softly. He did not stand up until the midwife handed his son to him. He was beside himself: at last he had an heir. He was overcome with gratitude – but to whom? To Heaven, to earth, to Grandmother’s deity, to the midwife? Grandmother was still on her knees, praying. Tired or overwhelmed, Father knelt again beside her, praying too, or at least appearing to.

Of course Father did not believe for a moment it was the Bodhisattva Guanyin who saved his wife and son. But he was very grateful to Grandmother. Perhaps her prayer did help him psychologically: it gave him a gleam of hope when everything else seemed to have failed; it kept him calm and it had a soothing effect on my mother and the midwife. Some time later when I reported to my parents that Grandmother was muttering her prayer again in our room, my father told me not to tell anybody else. Then he said to my mother: ‘I guess praying is better than killing people and burning factories.’

After the birth of my brother, my father changed into a different person. He was not as enthusiastic about his job as before. He used to work really hard, going out before I got up and coming home when I was asleep. Now he often drank on his own. He even had time to play with us. He seemed to have lost interest in the revolution that was going on. As a soldier he had killed his enemies, but that was to liberate the country. In the land reform of 1950, tens of thousands of landlords and rich farmers were executed because they were the enemies of the people, threatening the stability of the new China. He did not think twice even when his own father was labelled a landlord, though his family had hardly more than four acres of land and employed only two labourers. He could understand why Mao sent half a million intellectuals to labour camps in 1957 after they had criticized the Party openly and fiercely. But what was it all for now?

My father often said that in the thirty years of his revolutionary career, he had never seen so much harm done in the name of a cause. He could not understand how an ideal that had inspired so much devotion in him had gone so terribly wrong. He never said much but it was obvious he was losing heart. He did not mind Grandmother praying at home; he even bought her candles for the Day of Ghosts.

After I entered middle school, my teacher encouraged me to join the Communist Youth League, as an induction into the Party: it was not good enough simply to get good marks; the most important thing was to have the right political attitude – only then could our knowledge be truly useful. Father had insisted that my two sisters join. But when I asked him whether I should follow them, he was vague. ‘There is no hurry. You should concentrate on your studies,’ he told me. I never did join the Youth League.

In 1982, I gained a place in the English Department in Beijing University. I felt like the old Confucian scholar I read of in the Chinese classics, who finally made it in the imperial exams and wanted to tell the whole world about his happiness. Out of millions, only a few hundred were chosen. I had heard of Oxford and Cambridge, both of which were considerably older, but perhaps no university occupied the unique position of Beijing University, absolutely the academic and spiritual nerve of the country. Perhaps only a Chinese would fully appreciate my good fortune. It was students of Beijing University in 1919 who first created the slogan ‘Democracy and Science’, as the cure for the ills of a China at the mercy of all the Western powers. It was two professors from Beijing University who started the Communist Party of China. Mao went there to study at their feet. It was one of the fiercest battlegrounds in the Cultural Revolution, and again it was there that the deepest introspection on the Cultural Revolution took place, just when I arrived.

Self-searching was rampant throughout the country: its most public form was the Scar Literature, the outpouring of novels and memoirs describing the unbelievable cruelty of the Cultural Revolution, suffered by individuals as well as the whole nation. The students went a step further. What caused this suffering, unprecedented in Chinese history? Never before was the whole nation, hundreds of millions of people, allowed to think only one thought, speak with one voice, read only one man’s works, be judged by one man’s criteria. Never before were our traditions so thoroughly shaken up, destroying families, setting husbands against wives, and children against parents. Never before was our society turned so completely upside down. The Party was barely in control, with all its senior members locked up or killed. Workers did not work; farmers did not produce; scientists and artists were in labour camps; not criminals, but judges, lawyers and policemen were in prison; and young men and women were sent to the countryside in droves for re-education. On top of the physical devastation, the psychological impact on everyone was even more poisonous. The Cultural Revolution brought out the worst in people. They spied on, reported, betrayed and murdered each other – strangers, friends, comrades and families alike – and all in the name of revolution. So much hope, so much suffering and sacrifice, and for what?

There were heated debates in our dormitory, in the lecture halls, in the seminars after class, and in a tiny triangular space right in the heart of the campus. Freedom to think and openness to all schools of thought – the ethos of Beijing University from its very birth – were in full flower. Coming from a small sleepy city, I was like Alice in Wonderland, bewildered and exhilarated at the same time. Thoughts and ideas flooded in with the opening up of China to the outside world, after decades of isolation – we breathed them in like oxygen. ‘Democracy and Science’, the slogan raised seventy years earlier, came to the forefront again. Could this be the solution for China? Certainly it seemed time to try something new.

When I described to my parents the stimulating life on campus, my father wrote back immediately, warning me not to follow the crowd. ‘You’re still young,’ he said, ‘and have just begun your life in the wider world. You have no idea how politics work in China. I’ve been through it all. Liberal thinking is never a good thing. The crushing of the intellectuals in 1957 is a lesson. Find some books in the library and read them, you will see what I mean. As Mao said, students should study. I think you should talk to the Party Secretary in your department, reporting to him your wish to be educated, judged and accepted by the Party. You perhaps know that being a member will be of great help to you if you want to stay in Beijing and get a job in government departments after your graduation.’ He ended the letter with ‘These are words from my heart. I hope you remember them.’

While the students in Beijing University were busy exploring how democracy could be adapted to suit Chinese conditions, I was given the chance to go to Oxford. It was 1986. When Grandmother heard the news, she could not sleep for days: ‘You are just like the monk, going to the West for new ideas,’ she enthused. ‘It won’t be easy but if you are determined to do good, you will have people helping you. You will get there in the end. When you come back, you can help the country.’

Father was very happy for me too. He had learned that the West was not a dungeon as he had been made to believe. Nevertheless he still warned me, in the only language he knew – that of Communist jargon: decaying capitalist society was no Heaven, and I should be vigilant and not allow decadent bourgeois thoughts to corrupt me. He insisted on coming to Beijing to see me off. I thought it was unnecessary: his health was poor and the train to Beijing was slow and crowded and anyway I would be back in one year. Then he said something that made me understand. Just before I boarded the plane, I gave him a hug and asked him to take care of himself. For only the second time in my life I saw tears in his eyes – the first was when my brother was born. ‘Don’t worry about me. This is your big chance, you’ve got to take it. Look at me, look at your sisters, look at what society has come to. Don’t get homesick. There is nothing here for you to come back to.’ When I turned around and waved him goodbye, I was shocked, and sad. As someone who had devoted his entire life to the revolution, he must have been in total despair.

My father died in 1997. He was strong and had never taken a day’s sick leave. But his depression ruined his health. He came down with diabetes, and soon was paralysed and became blind. His old work unit, which was supposed to look after him, could not afford to pay his medical bills and he refused to let me do it for him. His last wish was to be buried not in a Western suit I had bought for him, nor a traditional Chinese outfit, but in a dark blue Mao suit. It was a difficult wish to gratify – nobody wore one any more. We searched for three days before we finally found one in a little shop on the outskirts of the city. We wanted him to be buried in it because it embodied his lifelong hopes, his ideals and unbounded faith, even though he had died a broken man.

Many of my father’s friends, colleagues and comrades from the army came to his funeral. The occasion, the gathering, brought out their own anger and frustration. I could understand their feelings; they were just as my father’s had been. They had sacrificed so much, gone through so much suffering and deprivation for the revolution – and now they were told what they had done was wrong. They must embrace this new world of markets and reform – but they could not; they felt they had no place in it; it was against all the beliefs they had held throughout their lives. Their whole raison d’être had been taken away. They were betrayed; they were even being blamed for what had gone wrong. The bitterness of loss was crushing and the void left in their hearts was deep. They found it impossible to cope with a past that had been cancelled and a future so uncertain.

As is the custom, my mother and my sisters prepared a meal with several dishes to thank the visitors for their sympathy and support – they had all brought presents, and gifts of money that was later used to pay off my father’s medical bills. Mother was moved – their lives were not easy either. To her surprise, many of them left the meat dishes and ate only the vegetables. These were people who used to drink with my father, and feast on all kinds of delicacies such as pig’s trotters and ox tails. ‘How come you have all turned into monks?’ she joked with them.

‘We can’t be monks. We are old Communists,’ one of them laughed, and then added, ‘it’s good for our health. And it’s better not to kill anything.’

I wanted to ask the old men about what they believed. In his last years my father often reminisced about Grandmother, and regretted his harshness towards her, especially selling her little statue of Guanyin. He did not become a Buddhist but in the twilight of their lives, I knew some of his oldest friends had actually turned to Buddhism, the very target of their earlier revolutionary fervour.

But before I had a chance to question them, they asked me if I had become a Christian. I shook my head, telling them I still did not know what to believe. ‘Many Chinese are going to church. You live in England and you don’t go to church?’ one of them said. ‘She should be a Buddhist,’ another one interrupted him. ‘She is Chinese after all. Buddhism is the best religion.’

Buddhism was making a come-back in China. In the early 1980s, the government had issued a decree allowing a limited revival of religion. As a Marxist would put it, the base had changed so the superstructure had to change too. The decree allowed for the 142 most important Buddhist monasteries damaged or destroyed in the Cultural Revolution to be restored or rebuilt. Monks and nuns in their orange and brown robes once more became a regular sight in towns and villages. In the cinema and on television, young people watched for the first time the lives of great Buddhist masters, albeit all kung fu wizards or martial arts heroes, who used their fantastic skills to save a pretty woman or impoverished villagers. The faithful could go to the temples, make offerings to the Buddha, draw bamboo slips to tell their families’ fortunes, and join monks and nuns in their chanting of the sutras and other Buddhist rituals. In a way, it resembled the old days when Buddhist monasteries were among the most important centres of Chinese life. They were a source of spiritual comfort but also of practical help with birth, illness, death and other crucial events in life. They received the infirm and the insane who were abandoned by their families and reviled by society. They gave the disillusioned and the discontented the perfect retreat, where they were asked no questions and given the space they needed. Many Communists, including senior Chinese leaders, had been sheltered in monasteries when they were hunted by the Nationalist government.

Observing these changes, I found myself thinking more and more about Grandmother. When I visited a temple, I would light incense for her; in the swirling smoke, the image of her counting beans in the night came back to me again and again. Sometimes I read a sutra and found the stories in it very familiar – they were among those she had told me in our long foot-washing sessions. The forbearance, the kindness, the suffering, the faith and the compassion were what she embodied. I felt many of the elements she had tried to instil in me were slowly becoming part of me. I began to see how extraordinary her faith was. She had suffered so much, enough to crush anyone, let alone such a frail person. Her faith kept her going, even though all she could do was to pray on her own in the dark, without temples and monks to guide her, and derided by her own family. Her beliefs made her strong despite her lifelong privations. She was illiterate but she knew the message that lies at the heart of Chinese Buddhism, the certainty and the solace. That is why she wanted me to follow her faith and acquire the strength it gave her. I never gave it a chance, rejecting it early on without really knowing what it was. Now I wished I could believe something so profoundly.

It was about the time of Father’s death that I decided to go on my journey and follow Xuanzang. I had been inspired through my early education by the idealism of Communism, but the intellectual ferment and questioning I was exposed to at Beijing University stayed with me. With Father’s death and the collapse of his world I lost all that remained of my attachment to the cause he gave his life to. I knew I was lucky, I was free and I had not suffered like my forebears and my fellow-countrymen. But like so many Chinese, I felt strongly that something was missing. The idea of a confirming faith dies hard. I was increasingly unsure of where I was going, why I was doing the things I did; I was at a loss, and pondering. Probably when I made the decision to go I wanted some clarity in my life, and the journey would give me a very clear objective.

Of course, I could have just sat in libraries and read about Xuanzang. But I knew that would not be enough. I did not think I could find a different outlook just by reading. The Chinese have a saying: ‘Read ten thousand books; walk ten thousand miles.’ I wanted to explore for myself, to make sense of everything I had been reading about Xuanzang and about Buddhism. He found his truth by going in search of the sutras – I had to go and look for mine.

It would be a spiritual journey for me but physically demanding too. Travelling along Xuanzang’s route would not be easy. In his time, covering those 16,000 miles through some of the world’s most inhospitable terrain, not knowing what he would encounter, required enormous courage and strength of will. What inspired him to brave the unknown and keep going for eighteen years, and what did he inspire in others? Was it the same faith that had sustained Grandmother? How did he maintain his equanimity and remain indifferent to flattering royalty and aggressive bandits? How did he manage to achieve so much? If I followed him, perhaps I would come to understand his life, his world and the tenets of Buddhism. I would also learn how much Buddhism has contributed to Chinese society, a fact well hidden from me and my fellow-countrymen. And perhaps I would find what I was missing.

When I told my mother about my plan, she exploded. Why was I going alone to those God-forsaken places in search of a man who died more than a thousand years ago? I must be out of my mind. Was I unhappy living in England? What was it for anyway? But she knew she could not stop me. I told her I would not be away for eighteen years. Many of the places Xuanzang visited no longer exist, or at least no one knows where they are; some, like Afghanistan, I could not visit. I would go only to the key places that mattered to him personally, and were important for the history of Buddhism. I would be travelling for no more than a year.

My little nephew Si Cong was also concerned. He had been completely gripped by yet another cartoon series of The Monkey King on television. It looked magnificent with the latest computer graphics and special effects. It was on every day at five o’clock when children came back from school. Would I have someone like the monkey to protect me? he asked me, while his eyes were fixed on the television. I said no. He quickly turned around. ‘What happens if you run into demons? They’re everywhere. Even the monkey can’t always beat them. You’ll be in big trouble.’ I told him the demons would not eat me because my flesh was not as tasty as the monk’s and it would not guarantee their longevity. He seemed relieved and went back to the magical world of The Monkey King.

It set me thinking, watching with him and looking at the steep mountains clad with snow, the deep turbulent rivers, the sandstorms that swept away everything in their path. Soon I would have to encounter them myself, not in fiction but in real life. I would pass through dangerous and strife-torn places; I might be robbed, or put in situations beyond my control. Whatever might happen, I would try to face it. Xuanzang would be my model and my guide.

TWO (#ulink_58449c2c-3a95-5ef4-88fb-e054f8fa3aad)

Three Monks at the Big Wild Goose Pagoda (#ulink_58449c2c-3a95-5ef4-88fb-e054f8fa3aad)

IN AUGUST 1999 I took a late-afternoon train from Handan, my home town, to Xian, the capital of the early emperors for much of the first millennium. It was where Xuanzang began and ended his travels. I was conscious that I was starting the most important journey of my life. But for the other people in my hard-sleeper compartment, the first order of business was food. As soon as the train started moving, the man opposite me produced a big plastic bag and unwrapped the contents. An amazing banquet slowly appeared: roast chicken, sausages, pot noodles, pickled eggs, cucumbers, tomatoes, melons and dried melon seeds, apples, pears, bananas and six cans of beer. The Chinese have suffered so much from starvation and famine that eating is rarely far from their minds. Everyone followed suit. Before long, they were sharing food, finding out each other’s names, where they were going, and why.

Privacy is not a concept we understand in China. We have lived far too long on top of each other, as in this six-bunk compartment, off a narrow corridor without doors. Conversation reduces the tension and makes life tolerable, but it is not small talk; more like an interrogation. After ten years in England where you can choose to live and die without knowing your neighbours, I was uncomfortable with the intrusion. I took out a book about Xuanzang and tried to read, but that was no protection. A single woman travelling on her own makes her fellow-passengers curious. Whether for business or pleasure, the Chinese like to do it in groups. Xuanzang tried very hard to find companions, but in vain, owing to the emperor’s prohibition against travelling abroad. I had also asked several monks myself. They were over the moon; pilgrimage to the land of the Buddha was the dream of every Buddhist – they would even gain merit from it should they need it for their rebirth in the Western Paradise. And to follow in the footsteps of Master Xuanzang! He was a model for them. His indomitability was an inspiration for them in their struggle for enlightenment. Many of the sutras they read every day, their spiritual sustenance, were his translations. His selflessness in giving his life to spreading Buddhism, not seeking his own salvation, was the ideal of the Bodhisattva, and of all Chinese monks. And for me, to see their reactions, to hear their thoughts, to ponder their reflections and to ask them questions – I would have learned so much more and understood Xuanzang better. I was not so fortunate, oddly enough for the same reason as Xuanzang: Chinese monks were not allowed to go abroad, unless they were on an official mission.

The men and women in my compartment quickly determined they were all going to Xian for business: the men were in engineering and the women in quality control. Then they turned to quizzing me, firing rapid questions like well-trained detectives. Who are you? Where are you going? Why? I told them I was following Xuanzang. They fell silent for a moment, then erupted into questions.

‘You mean you are really following that monk in TheMonkey King, the one who went to India? Are you really going all that way?’

I nodded.

‘Why? Are you a Buddhist?’

I had hardly finished answering him when the man sitting next to me put his hand on my forehead. I stiffened. ‘I want to see if you are running a fever,’ he said. His colleagues laughed and I relaxed.

‘If you really want to travel, why don’t you go to Europe, or America or Australia? I wouldn’t go to India if you paid me! It is so dirty, so poor, worse than China.’

‘If you want to write about Xuanzang, why don’t you talk to some academics in Xian and make it up? Do you really think all the scholars do such hard work? You must be joking.’

They went on for some time, trying to dissuade me. After the lights were switched off the woman above me knocked on the edge of my bunk. ‘You really shouldn’t make this trip,’ she said. ‘It’s too dangerous. Why don’t you join our group and have a good time in Xian?’

We arrived in Xian early next morning, by which point my companions seemed to have become used to the idea that I really was going on my journey. Perhaps they thought I was a bit crazy. The men all helped me with my luggage. I told them I could manage on my own. ‘Save your energy. You have a long way to go. You don’t have the Monkey King to help you. You must take care of yourself,’ they said, smiling and waving from the platform.