По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

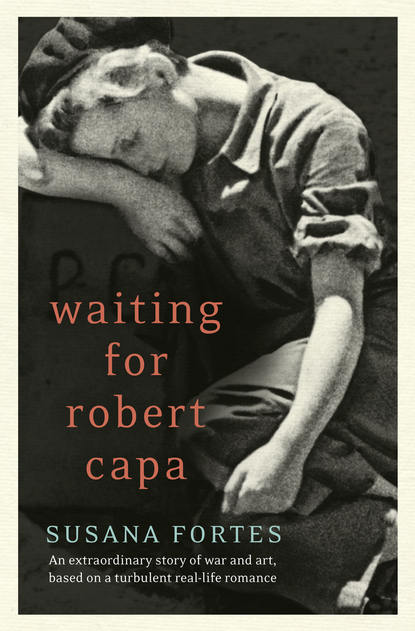

Waiting for Robert Capa

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

She never knew what the soul was. As a child, when they lived in Reutlingen, she believed that souls were the white diapers that her mother hung out to dry on the balcony. Oskar’s soul. Karl’s. Her own. But now she doesn’t believe in those things. The God of Abraham and the twelve tribes of Israel would break her neck if they could. She did not owe them anything. She preferred English poetry a million times over. One poem by Eliot can free you from evil, she thought; God didn’t even help me escape that Wächterstrasse prison.

It was true. She left by her own means, self-assured. Her captors must have thought that a blond girl, so young and so well-dressed, could not be a Communist. She thought it, too. Who would have known she would end up taking an interest in politics frequenting the tennis club in Waldau? A deep tan, white sweater, short pleated skirt … She liked the way exercise made her body feel, as well as dancing, wearing lipstick, donning a hat, using a cigarette holder, drinking champagne. Like Greta Garbo in The Saga of Gosta Berling.

Now the train had entered a tunnel, sounding a long whistle. It was completely dark. She breathed in a deep smell of railway emanating from the car.

She doesn’t know exactly when everything started to twist itself. It happened without her realizing it. It was because of the damn cinders. One day the streets started smelling like a railroad station. It reeked of smoke, of leather. Well-polished high boots, saddlery, brown shirts, belt buckles, military trappings … One Tuesday, as she was leaving the movie theater with her friend Ruth, she saw a group of young men in the Weissenhof district singing the Nazi hymn. The boys were just pups. They did not pay it further mind.

Later, it was prohibited to buy anything in Jewish stores. She remembered her mother being thrown out of a gentile store, bending over to pick up her scarf that had fallen in the doorway as a result of the shopkeeper’s push. That image was like a hematoma in her memory. A blue scarf speckled with snow. The burning of books and sheet music began around the same time. Afterward, the people began filling the arenas. Beautiful women, healthy men, honorable fathers with families. They weren’t fanatics, but normal people, aspirin vendors, housewives, students, even disciples of Heidegger. They all listened closely to the speeches, they weren’t being fooled. They knew what was happening. A choice had to be made and they chose. They chose it.

On March 18, at seven in the evening, she was detained by SA storm troopers at her parents’ home. It rained. They came looking for Oskar and Karl, but since they did not find them, they took her instead.

Broken locks, open armoires, emptied-out drawers, papers everywhere … During the search they found the last letter Georg had sent from Italy. According to them, it spewed Bolshevik garbage. What did they expect from a Russian? Georg was never able to talk about love without resorting to the class struggle. At least he had been able to flee and was out of danger. She told them the truth, that she had met him at the university. He studied medicine in Leipzig. They were sort of boyfriend and girlfriend, but they gave each other their own space. He never accompanied her to parties her friends invited her to and she never asked about his gatherings until dawn. “I was never interested in politics,” she told them. And she must have appeared convincing. One can suppose her attire helped. She wore the maroon skirt her aunt Terra had given her for graduation, high-heeled shoes, and a low-cut blouse, as if the SA had come to get her just as she was going out dancing. Her mother always said that dressing properly could save one’s life. She was right. Nobody placed a hand on her.

As they drove through the corridors toward her cell, she heard the shouting coming from interrogations taking place in the west wing. When it was her turn, she played her part well. An innocent young woman, and frightened. In reality, she was. But not enough to stop her from thinking. Sometimes, staying alive solely depends on keeping your head in place and your senses alert. They threatened to keep her in prison until Karl and Oskar turned themselves in, but she was able to persuade them that she really couldn’t supply them with any information. Choked voice, eyes wide-open, tender smile.

At night she stayed on her cot, silent, smoking, staring at the ceiling, her ego a bit bruised, wanting to end the whole charade once and for all. She thought about her brothers, praying that they’d been able to go underground, cross to Switzerland or Italy, like Georg. She also planned her escape for when she was able to get out of there. Germany was no longer her country. She wasn’t thinking of a temporary escape, but of starting a new life. All the languages she learned would have to come of some use. She had to find a way out. She’d do it. That she was sure of. This is why she had a star. The train came back out into the light again as the wagon clattered through the mountains. They had entered another landscape. A river, a farm surrounded by apple trees, hamlets with chimneys blowing smoke. Children playing on top of an embankment lifted their arms toward the edge of dusk, moving their hands from left to right as the train abandoned the last curve.

The first shooting star she saw was in Reutlingen, when she was five years old. They were walking back from their neighbor Jakob’s bakery with a poppy-seed cake and condensed milk for dinner. Karl was ahead, kicking rocks; she and Oskar always lagged behind, and so Karl, with his big-brother finger, pointed to the sky.

“Look, Little Trout.” He always called her that. “Make a wish.” Up there darkness was the color of prunes. Three little children, interlinking arms over shoulders, looking up at the sky, while they fell, two by two, three by three, like a handful of salt, those stars. Even now, when she remembers it, she can smell the wool from the sweater sleeves on her shoulders.

“Comets are a gift of good luck,” said Oskar.

“Like a birthday present?” she asked.

“Better. Because it’s forever.”

There are things that siblings just know, the kinds of details spies use to confirm identities. Memories that slither beneath the tall grass of childhood.

Karl was always the smartest of the three. He taught her how to behave if she were ever arrested and to use the secret codes of communication that the Young Communists used, like pounding out the letters to the alphabet through the walls. This, at least, helped earn her the respect of her fellow prisoners. In order to survive in prison, one must reinforce the mechanisms of mutual aid as much as possible. The more you know, the more you are worth. Oskar, on the other hand, explained to her how to build one’s inner strength for resistance. How to hide weakness, act with the utmost assurance, self-confidence. So that your emotions don’t betray you. One can smell fear, he’d tell her. You have to see it coming.

She looked around with suspicion. There was a passenger in her compartment, smoking cigarette after cigarette. He was dressed in black. In order to let some air into the compartment, he opened the window and propped his arms up on the pane. A very light rain spritzed her hair and refreshed her skin. I can smell him, she thought. He’s here, at my side. You have to think faster than they do, evaporate into the air, disappear, slip out, disappear however you can, become someone else, he told her. That’s how she learned how to create characters, just like she did when she was an adolescent playing with her friend Ruth in the attic, imitating silent-film actresses, posing provocatively, holding imaginary long-stemmed cigarettes between her fingers. Asta Nielsen and Greta Garbo. Surviving is escaping toward what’s next.

After two weeks, they let her go. April 4. There was a red dahlia and an open book on the windowsill. Her family’s efforts by way of the Polish consul proved effective. But she always believed that if she was let out of there, it was because of her star.

It is not a metaphor to feel the constellations’ influence on the world, and neither is questioning a mineral’s incredible precision for always pointing toward the magnetic pole. The stars have guided cartographers and sailors for millennia, sending messages for millions of light-years. If sound waves travel through the ether, then somewhere in the galaxy there must also be the Psalms, litanies, and prayers of men floating within the stars.

Yahweh, Elohim, Siod, Brausen, whoever you are, lord of the plagues and of the oceans, ruler of chaos and of annihilated masses, master of chance and destruction, save me. Entering beneath the iron arc of the Gare de l’Est station, the train made its way to the platform. On the other side of the window, a world of passengers on their daily commute. The young woman opened her notebook and began writing.

“When you don’t have a world to go home to, one has to trust their luck. Sangfroid and a capacity to improvise. These are my weapons. I’ve been using them since I was a little girl. That’s why I’m still alive. My name is Gerta Pohorylle. I was born in Stuttgart, but I’m a Jewish citizen with a Polish passport. I’ve just arrived to Paris, I’m twenty-four years old, and I’m alive.”

Chapter Two (#u1eb7add9-d54b-5773-be81-dad2513d616a)

The doorbell rang and she stood frozen before the kitchen oven, holding her breath, with the teapot still in hand. She wasn’t expecting anyone. In the dormer window, a gray cloud squashed the rooftops along the Rue Lobineau. The glass was broken and a strip of adhesive tape, which Ruth had carefully placed, still lay over it. They had shared that apartment since she first arrived in Paris.

Gerta bit her lip until it bled a little. She thought the fear had passed, but no. That was one thing she learned. That fear, the real kind, once it has installed itself into the body, never goes away. It remains there, crouched in the form of apprehension, though there is no longer any motive, and one finds themselves safe in a city of rooftops with dormers, free of jail cells where someone can be beaten to death. It was as if there was always a step missing on the staircase. I know this sensation, she said to herself, the rhythm of her breathing returning to normal, as if the adrenaline rush had tempered her will. The fear was now splattered across the tiles of their kitchen floor where she’d spilled her tea. She recognized it in the way you recognize an old traveling companion. Always knowing their whereabouts. You there. Me here. Each in their own place. Maybe it should be like this, she thought. When the loud ring of the doorbell sounded a second time, she placed the teapot on the table in slow motion, and prepared herself to open the door.

A thin young man with a hint of fuzz over his lip tilted toward her in a kind of bow before handing her a letter. It was in a long envelope, without any official postmarks but the Refugee Help Center’s blue-and-red stamp. Her name and address were written in all caps. As she opened the flap, she noticed the blood in her temples pulsing, slowly, like the accused must feel awaiting the verdict. Guilty. Innocent. She couldn’t quite understand what the letter said. And had to read it several times until the rigidness in her muscles subsided and the expression on her face began to change like the sun when it appears from behind a cloud. It wasn’t that she smiled, but that she was now smiling on the inside. It took over all the factions of her face, not only her lips but her eyes as well: her way of looking up at the ceiling as if the wings of an angel were fluttering above. There are things that only siblings know how to say. And once they say them, the entire universe shifts, everything is put back into its place. The passage of an adventure novel read out loud by children on porch steps before dinner can contain a secret code whose meaning no one else can interpret. That’s why when Gerta read, “Beneath his eyes, bathed in moonlight, lay a fortified enclosure, from which rose two cathedrals, three palaces, and an arsenal,” she could feel the heat from the oil lamp’s flame heading up the sleeves of her blouse. It illuminated the cover illustration of a man with his hands tied, walking behind a black horse being ridden by a Tartar over snow-covered lands. That’s when she knew with all certainty that the river was the Moscow River, the walled territory was the Kremlin, and that the city was Moscow. Just as it was described in the first chapter of Michael Strogoff. And she was at ease, because she understood that Oskar and Karl were safe.

The news filled her insides with energy, a kind of vital exhilaration that she needed to express immediately. She wanted to tell Ruth, Willi, and everyone else. She looked at herself in the moon that covered the door of the wardrobe. Hands deep in pockets, hair blond and short around the face, arched eyebrows. She was studying herself in a thoughtful and careful manner, as if she had just come face-to-face with a stranger. A woman barely five feet tall, with a tiny and muscular body similar to a jockey’s. Not overly pretty, not overly smart, just another of the 25,000 refugees that arrived in Paris that year. The cuffs of her rolled-up shirtsleeves over her arms, the gray pants, bony chin. She moved closer to the mirror and saw something in her eyes, a kind of involuntary obstinacy that she didn’t know how to interpret, nor did she want to. She limited herself to taking out a lipstick from the nightstand drawer, opening her mouth, and quickly outlining her smile in a fiery red bordering on shameless.

Sometimes you can find yourself hundreds of miles from home, in an attic in the Latin Quarter, with water stains on the ceiling and pipes that sound like the foghorn of a ship, not knowing what will become of your life. Without residency papers, and with little money except for when your friends in Stuttgart can find a way of shipping some over to you. You discover the oldest reasons for uprooting, feel the same desolation in your soul as all those who have been obliged to travel the longest thousand miles of their lives and look at themselves afterward in the mirror and discover that, despite it all, a desire to be happy is written on their faces. An enthusiastic resolution, irreducible, void of cracks. Perhaps, she thought, this smile will be my only safe-conduct. In those days, the reddest lips in all of Paris.

In a hurry, she grabbed her trench coat from the coat rack and went out into the morning of the streets.

For months now, the city of the Seine was a hotbed of thoughts and opinions, a place conducive to the bravest and brightest ideas. Montparnasse cafés, open at all hours, became the center of the world for the newly arrived. Addresses were exchanged, job opportunities sought, the latest news from Germany discussed, and every now and again one could get hold of a Berlin newspaper to read. In order to get a summary of the day’s news, it was customary to go from table to table along all the stops on the route. Gerta and Ruth would often make a date to meet at Le Dôme Café’s outside patio, and it was precisely where Gerta was headed. Walking in her peculiar way, hands in the pockets of her trench coat, shoulders hunched from the cold chill as she crossed the Seine. She enjoyed that ashen light, the generous schedules, the lead gutters on the roofs, the open windows, and the world’s ideas.

But Paris was not only that. Many considered the flood of refugees a burden. “The Parisians will embrace you and then leave you shivering in the street,” Ruth liked to say, and she was right. As it was done before in Berlin, Budapest, and Vienna, the fate of European Jews was now being written on the city’s walls. While passing in front of the Austerlitz station, where she was supposed to pick up a package, Gerta saw a group of young men from the Croix-de-Feu putting up anti-Semitic posters in the station, and before she knew it, night had fallen. Again, a bitter smell of gunpowder rose to her throat. It was unexpected and different from the fear that she had experienced at home when the doorbell rang. It was more like an uncontrollable eruption. A reckless sensation that caused her to scream, coarse and loud, with a voice that did not resemble her own in the least.

“Fascistes! Fils de pute!”

The rebuke was heard loud and clear, in perfect French. That’s exactly what she said. There were five of them. All were wearing leather jackets and high boots, like cocks with their spurs. But where the hell was her self-assurance and sangfroid? She had her regrets when it was already too late. An older man exiting the door from the post office looked her up and down with disapproval. The French, always so restrained.

The tallest one of the group became defiant and began walking toward her, taking big strides. She could have found safe haven in a store, café, or in the very post office, but she didn’t. It did not occur to her. She simply changed direction, cutting the corner onto a narrow street with balconies looming above. She walked, trying not to accelerate the pace, instinctively protecting herself by holding her handbag tightly over her abdomen. Aware of the footsteps behind her. Cautious. Without turning around to look. When she had barely made it around the entire block, she was able to perfectly hear, word for word, what the individual on her trail had directed at her. A voice as cutting as a handsaw. And that’s when she started running. As fast as she could. Without caring about where she was going, as if her running had nothing to do with the threat she’d just heard but with another reason. Something inside, blocking her, as if she were being held captive in a labyrinth. And she was. Her mouth was dry, and she felt a pang of shame and humiliation heading up her esophagus, like the time when she was a child at school and her classmates poked fun at her customs. She went back to being that little girl in a white blouse and plaid skirt, forbidden to touch coins during the Sabbath. Someone who, deep down in her soul and with all her might, hated being Jewish, because it made her vulnerable. Being Jewish was a blue scarf speckled with snow in a doorway of a spice shop, her mother crouched over and keeping her head low. Now she was dodging the passersby she was brusquely meeting head-on, making them do a double-take: a young woman in such a rush could only be trying to escape herself. She took a quick left onto a passageway with gray mansard roofs and a smell of cauliflower soup that turned her stomach. And there she had no choice but to stop. At a corner, she grabbed onto a lead gutter and vomited all the tea from breakfast.

It was after twelve when she finally arrived at Le Dôme Café. Her skin moist with sweat, her hair wet and pushed back.

“What on earth happened to you?” asked Ruth.

With shoulders hunched, Gerta sank her hands into her pockets and made herself comfortable in one of the wicker chairs without responding. Or if she had, it was done in an elusive manner.

“I want to go to Chez Capoulade tonight” was all she offered. “If you want to join me, fine. If not, I’ll go alone.”

Her friend’s expression grew serious. Her eyes appeared to be busy forming opinions, jumping to their own conclusions. She knew Gerta all too well.

“Are you sure?”

“Yes.”

That could mean a number of things, thought Ruth. And one of them meant going back to the beginning. Winding up in the same place they thought they had escaped. But she kept quiet. She understood Gerta. How could she not? If she herself wanted to curl up and die each time she was at the Center for Refugees’ section 4, where she worked, and was obliged to turn the newly arrived away, to other neighborhoods, where it was known that they’d also be rejected because there was no longer a way to offer shelter and food to everyone? The largest flood of refugees had arrived at the worst moment, just as unemployment was at its highest. The majority of the French believed they’d take the bread right out of their mouths; that’s why there were more anti-Semitic protests in the streets. It was a bandwagon that had started in Germany and that was dangerously spreading everywhere.

Most of the refugees had to pass around the same 1,000-franc bill to present to the French customs authorities to prove their income and be granted entrance permission. But Gerta and Ruth were never as defenseless. Both were young and attractive, they had friends, spoke languages, and they knew what to do in order to get by.

“What you need is a real easygoing guy,” said Ruth, lighting a cigarette and making it clear she wanted to change the subject. “Maybe that way you’ll be less likely to complicate your life. Face it, Gerta, you don’t know how to be alone. You come up with the most absurd ideas.”

“I’m not alone. I have Georg.”

“Georg is too far away.”

Ruth directed her gaze at Gerta again, and this time with a look of disapproval. She always wound up playing the nurse, not because she was a few years older but because that’s how things had always been between them. It worried Ruth that Gerta would get into trouble again, and she tried her best to help Gerta avoid it, unaware that sometimes destiny switches the cards on you so that while you’re busy escaping the dog, you find yourself facing the wolf. The unexpected always arrives without any signs announcing it, in a casual manner, the same way it could simply choose to never arrive. Like a first date or a letter. They all eventually arrive. Even death arrives, but with this, you have to know how to wait.

“Today, I met a semi-crazy Hungarian,” Ruth added with a complicit wink. “He wants to photograph me. He said he needs a blonde for an advertisement series he’s working on. Imagine, some Swiss life insurance company…” she said, and then her face lit up with a smile that was part mocking, part mild vanity.

The reality was, anyone could have imagined her in one of those ads. Her face was the picture of health, rosy and framed by a blond bob parted to the left, with a patch of waves over her forehead that gave her the air of a film actress. Next to her, Gerta was undeniably a strange beauty with her gamin haircut, her severe cheekbones and slightly malicious eyes with flecks of green and yellow.

Now the two were laughing out loud, slouching in their wicker chairs. That’s what Gerta liked most about her friend: the ability to always find the funny side to things, take her out of the darkest corners of her mind.

“How much is he going to pay you?” she asked in all pragmatism, never forgetting that however appealing the idea was to them, they were still trying to survive. And it wasn’t the first time that modeling had paid a few days’ rent or at least a meal out, for them.