По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

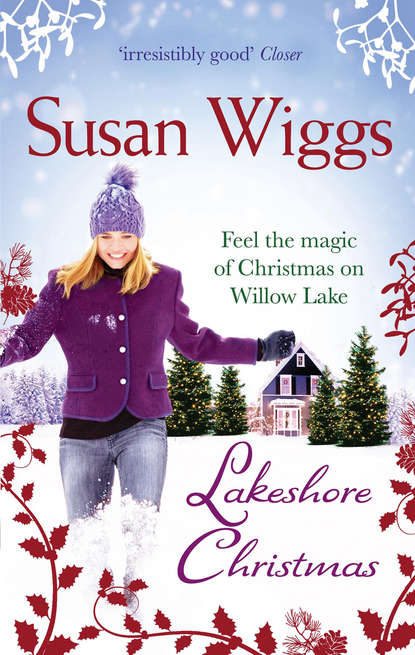

Lakeshore Christmas

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

They didn’t call Meredith, the oldest. Meredith was a doctor in Albany. She was always on duty or on call and at any given time, she was considered too busy to bother. Renée, the next oldest, had three kids, which meant three thousand reasons Renée could never be the go-to girl. Their brother, Guy, was, well, a guy, reason enough to leave him be. That left Maureen, the middle sibling. She was the one they called when they suddenly needed something—companionship, an errand runner, someone to chat with on the phone, a babysitter.

Here was what drove her crazy—not that she was the one they called, but that they assumed she never had anything better to do.

“We could get takeout and watch goofy old holiday movies,” Janet wheedled. “Come on, it’ll be fun. You remember fun, right? Fun is good.”

“What?”

“I said—”

“Never mind. I’ve got something I’m doing tonight,” she told Janet.

“Really? What’s going on? Do you have a date? Oh, my God, you have a date,” Janet exclaimed without giving Maureen a chance to respond. “Who is it? Walter Grunion? Oh, I know. Ned Farkis. He ran into Karl on the train and asked about you. Oh, my God, you’re going out with Ned Farkis.”

Maureen laughed aloud. “I’m glad you have my evening all figured out for me. Ned Farkis. Give me a break.” Ned was a pharmacist’s assistant at the local Rexall. He’d asked her out several times, and she’d never said a clear no, but she never said yes, either. Then she felt guilty about her scorn, because she knew there were guys out there—many, many guys—who had exactly that kind of opinion of her—Maureen Davenport? Give me a break.

“Seriously,” she said to Janet, “I’m meeting Olivia. We’re going to the church to help construct the nativity scene.”

“Oh. I didn’t know you were on that committee, too.”

“I’m not. Not officially, anyway. But since I’m working on the pageant—”

“I get it. Today the pageant, tomorrow the world.”

“Very funny. You could join us,” she suggested.

“Us?”

“The volunteers at church.”

“It’s kind of a long drive for me,” Janet said.

Yet she’d been perfectly willing for Maureen to drive it. Maureen tried not to feel exasperated. “Have a nice night, Janet,” she said.

“Sure will. Love you!”

Maureen was blessed to belong to a family where everybody loved each other. Her parents had been college sweethearts who made their home in Avalon because it was a place of natural beauty, a place where they wanted to have lots of kids and raise them surrounded by small-town safety and the richness of nature. All five of their children still lived in or near Avalon.

This was not to say life for the Davenports had been easy. Far from it. Her mother had died of a virus that went straight to her heart. Stan Davenport, a high school principal, had been left with a houseful of kids. Maureen was just five years old when it had happened. She remembered the livid pain of loss, a memory as stark as an old photograph. Meredith had cried so hard, she’d made herself throw up, and Guy had turned their mother’s name into an endless string of tragic sobs: “Mama. Mama. Mama.” Their father had sat at the dining room table with his head propped in his hands, his shoulders shaking, Janet and Renée clinging to him, too young to grasp anything but the fact that in a single instant, their world had exploded. Maureen understood everything, young as she was. Dad had looked like a stranger to her. A complete stranger who had wandered into the wrong house, the wrong family.

In time, they had all learned to smile again, to find the joys in life. And eventually, her father had married Hannah, who adored the children and mothered them as fiercely and devotedly as if she’d given birth to them. One of the reasons Maureen loved Christmas so much was that Hannah always set aside time at the holiday for each child to spend remembering their mother. This meant there were tears, sometimes even anger, but ultimately, it meant their mother lived in their hearts no matter how long she’d been gone.

Only now, as an adult, could Maureen truly appreciate Hannah’s great generosity of spirit. They were a close family, and this time of year was the perfect time to remember the many ways she was blessed. Even in the face of the biggest professional disaster of her career, she could still feel blessed.

Maureen loved everything about Christmas—the cold nip in the air and the crunch of snow underfoot. The aroma of baking cookies and the twinkle of lights in shop windows and along roof lines. The old songs drifting from the radio, sentimental movies on TV, stacks of Christmas books on library tables, the children’s artwork on display. The cheery clink of coins in the Salvation Army collection bucket and the fellowship of people working together on holiday projects.

All of this made her feel a part of something. All of this made her feel safe. Yes, she loved Christmas.

Five

Eddie Haven couldn’t stand Christmas. It was his own private hell. His aversion had started at a young age, and had only grown stronger with the passage of years. Which did not explain why he was on his way to help build a nativity scene in front of the Heart of the Mountains Church.

At least he didn’t have to go alone. His passengers were three brothers who had been categorized at the local high school as at-risk teens. Eddie had never been fond of the label, “at-risk.” As far as he could tell, just being a teenager was risky. Tonight, three of them were his unlikely allies, and at the moment they were arguing over nothing, as brothers seemed to do. Tonight was all about keeping the boys occupied. One of the main reasons they were at risk was that they had too much time on their hands. He figured by putting their hands on hammers and hay bales, they’d spend a productive evening and stay out of trouble.

“Hey, Mr. Haven,” said Omar Veltry, his youngest charge. “I bet you five dollars I can tell you where you got them boots you’re wearing.”

“What makes you think I even have five dollars?” Eddie asked.

“Then bet me,” Omar piped up. “Maybe I’ll lose and you’ll get five dollars off me. Five dollars says I can tell you where you got those boots.”

“Hell, I don’t even know where I got them. So go for it.”

“Ha. You got those boots on your feet, man.” Omar nearly bounced himself off the seat. He high-fived each brother in turn and they all giggled like maniacs.

Christ. At a stoplight, Eddie dug in his pocket, found a five. “Man. You are way too smart for me. All three of you are real wiseguys.”

“Ain’t we, though?”

“I bet you’re smart enough to put that fiver in the church collection box,” Eddie added.

“Oh, man.” Omar collapsed against the seat.

Heart of the Mountains Church was situated on a hillside overlooking Willow Lake, its slender steeple rising above the trees. The downhill-sloping road bowed out to the left near the main yard of the church, and a failure to negotiate the curve could mean a swift ride to disaster. Eddie slowed the van. No matter how many times he rounded this curve in the road, he always felt the same shudder of memory. This was where the two halves of his life had collided—the past and the future—one snowy night, ten years ago.

Tonight, the road was bare and dry. The iconic church was the picture of placid serenity, its windows aglow in the twilight, the landscape stark but beautiful, waiting for the snow. This, Eddie figured, was the sort of setting people imagined for weddings and holiday worship, community events—and of course, AA meetings.

He pulled into the church parking lot. “I’m officially broke now. Thanks a lot.”

“I heard you used to be a movie star,” Randy, the older brother, pointed out. “Everybody knows movie stars are rich.”

“Yeah, that’s me,” Eddie said. “Rich.”

“Betcha you’re rich from that movie,” the middle brother, Moby, pointed out. “I saw it on TV just the other night. ‘There’s magic in Christmas, if only you believe,’” he quoted. It was a famous line in The Christmas Caper, uttered by a wide-eyed and irresistible little Eddie. The damn thing aired endlessly like a digital virus every holiday season.

“Now you’re officially on my nerves,” said Eddie. “And FYI, I’m not rich from the movie. Not even close.”

“Huh,” Moby said with a snort of disbelief. Moby was his nickname, based not on his size, but on the fact that his given name was Richard. “Your movie’s huge. It’s on TV every Christmas.”

“Maybe so, but that doesn’t do me a bit of good.”

“You don’t, like, get a cut or anything?”

“Geez, don’t look at me like that. I was a kid, okay? And my parents didn’t do so hot, being in charge of finances.” The Havens had been incredibly naive, in fact. Against all odds and conventional wisdom, they’d managed to fail to make money off one of the most successful films of the year.

Maybe that was why he avoided his folks like poison ivy around the holidays. Oh, please let it not be so, Eddie thought. He didn’t want to be so shallow. But neither did he want to try figuring out the real reason he steered clear of family matters at Christmas.

“Did they, like, take your money and spend it on cars and stuff?” Randy asked. “Or make stupid investments?”

“It’s complicated,” Eddie said. “To make a long story short, they signed some contracts without quite knowing what they were agreeing to, and none of us saw any earnings. It was a long time ago,” he added. “Water under the bridge.”