По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

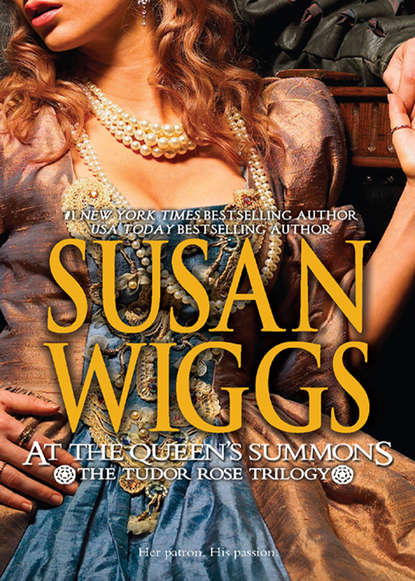

At The Queen's Summons

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“I shouldn’t—”

“Yet you do,” she insisted. “You do in spite of yourself.”

He did not deny it, but crossed his arms on the table and leaned forward. “What is all this?”

“My things.” She patted the limp, dusty bag she had worn tied to her waist the first day they had met. “It is uncanny how little one actually needs in order to survive. All I ever had fits in this bag. Each object has a special meaning to me, a special significance. If it does not, I get rid of it.”

She rummaged with her hand in the bag and drew out a seashell, placing it on the table between them. It was shiny from much handling, bleached white on the outside while the inner curve was tinted with pearly shades of pink in graduated intensity.

“I don’t remember ever actually finding this. Mab always said I was a great one for discovering things washed up on shore, and from the time I was very small, I would bring her the most marvelous objects. Apples to juggle, a pessary of wild herbs. One time I found the skull of a deer.”

She took out a twist of hair, sharply contrasting black and white secured with a bit of string.

“I hope that’s not poor Mab,” Aidan commented.

She laughed. “Ah, please, Your Magnificence. I am not so bloodthirsty as that.” She stroked the lock. “This is from the dog I was with when Mab found me. Mab swore the beast saved me from drowning. He was half drowned himself, but he revived and lived with us. She said I told her his name was Paul.”

She propped her chin in her cupped hand and gazed at the whitewashed wall by the window, where the morning sun created colored ribbons of light on the plastered surface. “The dog died four years after Mab found us. I barely remember him, except—” She stopped and frowned.

“Except what?” asked Aidan.

“During storms at night, I would creep over to his pallet and sleep.” She showed him a few more of her treasures—a page from a book she could not read. He saw that it was from an illegal pamphlet criticizing the queen’s plans to marry the Duke of Alençon. “I like the picture,” Pippa said simply, and showed him a few other objects: a ball of sealing wax and a tiny brass bell—“I nicked it from the Gypsy wagon”—flint and steel, a spoon.

It was, Aidan realized with a twinge of pity, the flotsam and jetsam of a hard life lived on the run.

And then, almost timidly, she displayed things recently collected: his horn-handled knife, which he hadn’t the heart to reclaim; an ale weight from Nag’s Head Tavern.

She looked him straight in the eye with a devotion that bordered discomfitingly on worship. “I have saved a memento of each day with you,” she told him.

A tightness banded across his chest. He cleared his throat. “Indeed. Have you naught else to show me?”

She took her time putting all her treasures back in the bag. She worked so slowly and so deliberately that he felt an urge to help her, to speed her up.

The message he had received still burned in his mind. He had a potential disaster awaiting him in Ireland, and here he sat, reminiscing with a confused, possibly deluded girl.

The letter had come all the way from Kerry, first by horseman to Cork and then by ship. Revelin, the gentle scholar of Innisfallen, had sounded the alarm about a band of outlaws roving across Kerry, pillaging at will, robbing even fellow Irish, inciting idle men to rise against their oppressors. Revelin reported that the band had reached Killarney town and gathered around the residence of Fortitude Browne, recently appointed constable of the district. And a hated Englishman.

Revelin was not certain, but he suggested the outlaws would try to take hostages, perhaps Fortitude’s fat, sniveling nephew, Valentine.

Aidan crushed his hands together as a feeling of powerlessness swept over him. He could do nothing from here in London. Queen Elizabeth had summoned him to force him to submit to her and then to regrant his lands to him. Just to show her might, she had kept him waiting. He battled the urge to storm out of London without even a by-your-leave. But that would be suicide—both for him and for his people. Elizabeth’s armies in Ireland were the instruments of her wrath.

Just as Felicity had been.

He would write back to Revelin, of course, but beyond that, he could only pray that cooler heads prevailed and the reckless brigands dispersed.

“I must show you one more thing,” Pippa said, snapping him out of his reverie.

He looked into her soft eyes and for no particular reason felt a lifting sensation inside him.

Something about her touched him. She reminded him of the hardscrabbling people of his district and their stubborn struggle against English rule. Her determination was as stout as that of his father, who had died rather than submit to the English. And yes—Pippa reminded him of Felicity Browne—before the cold English beauty had shown her true colors.

“Very well,” he said, trying to clear his mind of the potential disaster seething back in Ireland. “Show me one more thing.”

She took a deep breath, then released it slowly as she placed her fisted hand on the table. With a deliberate movement she turned her hand over to reveal a sizable yet rather ugly object of gold.

“It’s mine,” she declared.

“I never said it wasn’t.”

“I was worried you might. See?” She set it down. “It looks odd now, but it wasn’t always. It was pinned to my frock when Mab found me.” She angled it toward him. “It’s got a hollow interior, as if something once fit inside. The outside used to have twelve matched pearls around a huge ruby in the middle. Mab said this pin, and the finely made frock I wore, are proof that I came from the nobility. What think you, my lord? Am I of noble stock?”

He studied her, the elfin features, the wide, fragile eyes, the expressive mouth. “I think you were made by fairies.”

She laughed and continued her tale. “Each year, Mab sold one of the pearls. After she died, I tried to sell the ruby, but I was accused of stealing it and I had to run for my life.”

She spoke matter-of-factly, even with an edge of wry humor, but that did not banish the image in his mind of a hungry, frightened young girl escaping the law.

“So now all I have left is this.” She turned it over and pointed to some etchings on the back beneath the pin. “I’m quite certain I know what these symbols mean.”

“Oh?” He grinned at her earnest expression.

“They are Celtic runes proclaiming the wearer of this brooch to be the incarnation of Queen Maeve.”

“Indeed.”

She shrugged. “Have you a better idea?”

He angled the brooch so that the sunlight picked out every detail of the etching. He started to nod his head and gamely declare that Pippa was absolutely right, when a memory teased him.

These were no random designs, but writings in a different alphabet. Not Hebrew or Greek; he had studied those. Then why did it look so familiar?

Frowning, Aidan found parchment and stylus. While Pippa watched in fascination, he carefully copied down the symbols, then turned the page this way and that, frowning in concentration.

“Aidan?” Pippa spoke loudly. “You’re staring as if it’s the flaming bush of Moses.”

He handed back the pin. “It’s very nice, and I have no doubt you are Queen Maeve’s descendant.” Absently, he tucked away the copy he had made. “Tell me. You faced starvation many times rather than selling that piece of gold. Why did you never try to pawn or trade it?”

She clutched the pin to her chest. “I will never give this up. It is the only thing I belong to. The only thing that belongs to me. When I hold it in my hand, sometimes I can—” She bit her lip and squeezed her eyes shut.

“Can what?”

“Can see them.” She whispered the words.

“See them?”

“Yes,” she said, opening her eyes. “Aidan, I have never told this to another living soul.”

Then don’t tell me, he wanted to caution her. Don’t make me privy to your dreams, for I cannot make any of them come true.