По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

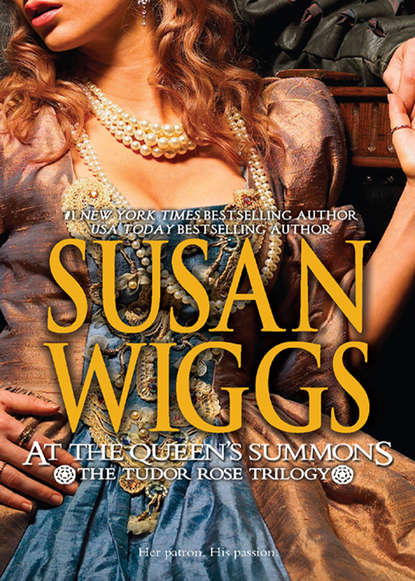

At The Queen's Summons

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

The emptier ever dancing in the air,

The other down, unseen and full of water;

That bucket down and full of tears am I,

Drinking my griefs, whilst you mount up on high.

—William Shakespeare

Richard II (IV, i, 184)

From the Annals of Innisfallen

In accordance with ancient and honorable tradition, I, Revelin of Innisfallen, take pen in hand to relate the noble and right valiant histories of the clan O Donoghue. This task has been done by my uncle and his uncle before him, since time no man can remember.

Canons we are, of the most holy Order of St. Augustine, and by the grace of God our home is the beechwooded lake isle called Innisfallen.

Those before me filled these pages with tales of fabled heroes, mighty battles, cattle raids and perilous adventures. Now the role of the O Donoghue Mór has fallen to Aidan, and my work is to chronicle his exploits.

But—may the high King of Heaven forgive my clumsy pen—I know not where to begin. For Aidan O Donoghue is like no man I have ever known, and never has a chieftain been faced with such a challenge.

The O Donoghue Mór, known to the English as Lord of Castleross, has been summoned to London by the she-king who claims the right to rule us. I wonder, with shameful, un-Christian relish, after clapping eyes on Aidan O Donoghue and his entourage, if Her Sassenach Majesty will come to regret the summons.

—Revelin of Innisfallen

One

“How many noblemen does it take to light a candle?” asked a laughing voice.

Aidan O Donoghue lifted a hand to halt his escort. The English voice intrigued him. In the crowded London street behind him, his personal guard of a hundred gallowglass instantly stopped their purposeful march.

“How many?” someone yelled.

“Three!” came the shout from the center of St. Paul’s churchyard.

Aidan nudged his horse forward into the area around the great church. A sea of booksellers, paupers, tricksters, merchants and rogues seethed around him. He could see the speaker now, just barely, a little lightning bolt of mad energy on the church steps.

“One to call a servant to pour the sack—” she reeled in mock drunkenness “—one to beat the servant senseless, one to botch the job and one to blame it on the French.”

Her listeners hooted in derision. Then a man yelled, “That’s four, wench!”

Aidan flexed his legs to stand in the stirrups. Stirrups.Until a fortnight ago, he had never even used such a device, or a curbed bit, either. Perhaps, after all, there was some use in this visit to England. He could do without all the fancy draping Lord Lumley had insisted upon, though. Horses were horses in Ireland, not poppet dolls dressed in satin and plumes.

Elevated in the stirrups, he caught another glimpse of the girl: battered hat crammed down on matted hair, dirty, laughing face, ragged clothes.

“Well,” she said to the heckler, “I never said I could count, unless it be the coppers you toss me.”

A sly-looking man in tight hose joined her on the steps. “I saves me coppers for them what entertains me.” Boldly he snaked an arm around the girl and drew her snugly against him.

She slapped her hands against her cheeks in mock surprise. “Sir! Your codpiece flatters my vanity!”

The clink of coins punctuated a spate of laughter. A fat man near the girl held three flaming torches aloft. “Sixpence says you can’t juggle them.”

“Ninepence says I can, sure as Queen Elizabeth’s white arse sits upon the throne,” hollered the girl, deftly catching the torches and tossing them into motion.

Aidan guided his horse closer still. The huge Florentine mare he’d christened Grania earned a few dirty looks and muttered curses from people she nudged out of the way, but none challenged Aidan. Although the Londoners could not know he was the O Donoghue Mór of Ross Castle, they seemed to sense that he and his horse were not a pair to be trifled with. Perhaps it was the prodigious size of the horse; perhaps it was the dangerous, wintry blue of the rider’s eyes; but most likely it was the naked blade of the shortsword strapped to his thigh.

He left his massive escort milling outside the churchyard and passing the time by intimidating the Londoners. When he drew close to the street urchin, she was juggling the torches. The flaming brands formed a whirling frame for her grinning, sooty face.

She was an odd colleen, looking as if she had been stitched together from leftovers: wide eyes and wider mouth, button nose, and spiky hair better suited to a boy. She wore a chemise without a bodice, drooping canion trews and boots so old they might have been relics of the last century.

Yet her Maker had, by some foible, gifted her with the most dainty and deft pair of hands Aidan had ever seen. Round and round went the torches, and when she called for another, it joined the spinning circle with ease. Hand to hand she passed them, faster and faster. The big-bellied man then tossed her a shiny red apple.

She laughed and said, “Eh, Dove, you don’t fear I’ll tempt a man to sin?”

Her companion guffawed. “I like me wenches made of more than gristle and bad jests, Pippa girl.”

She took no offense, and while Aidan silently mouthed the strange name, someone tossed a dead fish into the spinning mix.

Aidan cringed, but the girl called Pippa took the new challenge in stride. “Seems I’ve caught one of your relatives, Mort,” she said to the man who had procured the fish.

The crowd roared its approval. A few red-heeled gentlemen dropped coins upon the steps. Even after a fortnight in London Aidan could ill understand the Sassenach. They would as lief toss coins to a street performer as see her hanged for vagrancy.

He felt something rub his leg and looked down. A sleepy-looking whore curved her hand around his thigh, fingers inching toward the horn-handled dagger tucked into the top of his boot.

With a dismissive smile, Aidan removed the whore’s hand. “You’ll find naught but ill fortune there, mistress.”

She drew back her lips in a sneer. The French pox had begun to rot her gums. “Irish,” she said, backing away. “Chaste as a priest, eh?”

Before he could respond, a high-pitched mew split the air, and the mare’s ears pricked up. Aidan spied a half-grown cat flying through the air toward Pippa.

“Juggle that,” a man shouted, howling with laughter.

“Jesu!” she said. Her hands seemed to be working of their own accord, keeping the objects spinning even as she tried to step out of range of the flying cat. But she caught it and managed to toss it from one hand to the next before the terrified creature leaped onto her head and clung there, claws sinking into the battered hat.

The hat slumped over the juggler’s eyes, blinding her.

Torches, apple and fish all clattered to the ground. The skinny man called Mort stomped out the flames. The fat man called Dove tried to help but trod instead upon the slimy fish. He skated forward, sleeves ripping as his pudgy arms cartwheeled. Just as he lost his balance, his flailing fist slammed into a spectator, who immediately threw himself into the brawl. With shouts of glee, others joined the fisticuffs. It was all Aidan could do to keep the mare from rearing.

Still blinded by the cat, the girl stumbled forward, hands outstretched. She caught the end of a bookseller’s cart. Cat and hat came off as one, and the crazed feline climbed a stack of tomes, toppling them into the mud of the churchyard.

“Imbecile!” the bookseller screeched, lunging at Pippa.

Dove had taken on several opponents by now. With a wet thwap, he slapped one across the face with the dead fish.

Pippa grasped the end of the cart and lifted. The remaining books slid down and slammed into the bookseller, knocking him backward to the ground.

“Where’s my ninepence?” she demanded, surveying the steps. People were too busy brawling to respond. She snatched up a stray copper and shoved it into the voluminous sack tied to her waist with a frayed rope. Then she fled, darting toward St. Paul’s Cross, a tall monument surrounded by an open rotunda. The bookseller followed, and now he had an ally—his wife, a formidable lady with arms like large hams.