По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

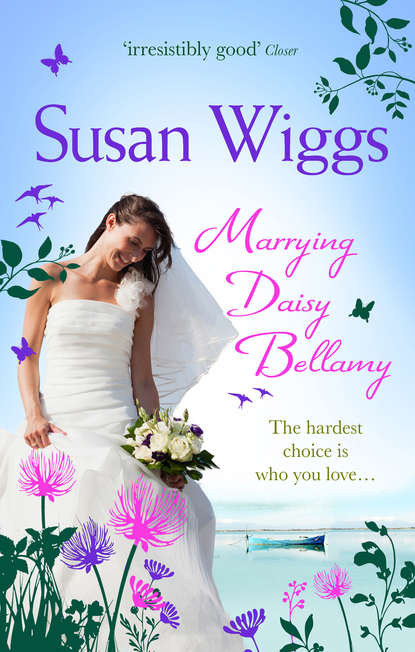

Marrying Daisy Bellamy

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

It wasn’t the kind of personal history that gave rise to a host of adoring relatives. Could be that was why he was so at home in the service. The people he trained with and worked with felt like family.

As usual, his mind wandered to Daisy. She came from a big extended family, which was one of the many things he loved about her, yet it was also one of the reasons he had trouble imagining a future with her. His duties meant she’d have to tell them all goodbye. It was a hell of a lot to ask of someone.

Flipping through the mail, he came to a small envelope, pre-addressed to him. He ripped into it, and his face lit up with a grin.

Everything fell away, his worries about the ceremony, the pain in his shoulder, the fact that he had a presentation due tomorrow, everything.

He stared down at the simple reply card: “Daisy Bellamy

? will___will not attend.” At the bottom, she’d scribbled, “Wouldn’t miss it! Bringing camera. See you soon.—XO.”

He was in a great mood by the time he got back to his room. Davenport, one of his suite mates, took one look at his face and asked, “Hey, did you finally get laid, Jughead?”

Julian simply laughed and grabbed a bottle of Gatorade from the fridge.

“You must have finished your presentation, then,” said Davenport.

“Barely started it.”

“What’s the topic again?”

“Survivable Acts in Combat.”

“Which means it’ll be a very short list, eh? No wonder you’re not worrying.”

“You’d be surprised what disasters a person can survive,” Julian said.

“Fine. Surprise me.” Davenport swiveled away from his computer screen and waited.

“Parachute mishap, if you can find a soft place to fall,” Julian said, rotating his sore shoulder.

“Ha-ha. Give me a rocket-propelled grenade over that, any day.”

“A grenade can be survivable.”

“Not to the guy who throws himself on top of it to save his buddies.”

“You want to throw the thing back where it came from, ideally.”

“Good to know,” said Davenport.

Julian wasn’t worried about the topic. The hard part of life did not involve physical tasks and academic achievement. He could do school, no worries. He could run a marathon, swim a mile, do chin-ups one-handed. None of that was a problem.

He was challenged by things that came easily to most other people, like figuring out life’s biggest mystery—how love worked.

That was about to change.

There was no textbook or course of study to show him the way, though. Maybe it was like getting caught in a wind shear. You had to hang on, navigate as best you could and hope to land in one piece. That was kind of what he’d always done.

February 2007

Julian stared at the cover letter from the United States Secretary of the Air Force. He couldn’t believe his eyes. Three different ROTC detachments had admitted him, and now he had confirmation of his scholarship. Crushing the formally worded notice against his chest, he stood in the middle of a nondescript parking lot and looked up at the colorless sky over Chino, California. He was going to college. And he was going to fly.

Although bursting with the news, he couldn’t find anyone to tell. He tried to explain it in rapid-fire street Spanish to his neighbor, Rojelio, but Rojelio was late for work and couldn’t hang out with him. After that, Julian ran all the way to the library on Central Ave., barely sensing the pavement beneath his feet. He didn’t have a home computer, and he had to get his reply in right away.

The author John Steinbeck referred to winter in California as the bleak season, and Julian totally got that. It was the doldrums of the year. Chino, a highway town east of L.A., was hemmed in by smog to the west and mountain inversions to the east, often trapping the sharp, ripe smell of the stockyards, which tainted every breath he took. He tended to hole up in the library, doing homework, reading … and dreaming. The summer he’d spent at Willow Lake felt like a distant dream, misty and surreal. It was another world, like the world inside a book.

To make sure the other kids didn’t torture him at his high school, Julian had to pretend he didn’t like books. Among his friends, being good at reading and school made you uncool in the extreme, so he kept his appetite for stories to himself. To him, books were friends and teachers. They kept him from getting lonely, and he learned all kinds of stuff from them. Like what a half orphan was. Reading a novel by Charles Dickens, Julian learned that a half orphan was a kid who had lost one parent. This was something he could relate to. Having lost his dad, Julian now belonged to the ranks of kids with single moms.

His mom had never planned on being a mom. She’d told him so herself and, in a moment of over-sharing, explained that he’d been conceived at an aerospace engineering conference in Niagara Falls, the result of a one-night stand. His father had been the keynote speaker at the event. His mother had been an exotic dancer performing at the nightclub of the conference hotel.

Nine months later, Julian had appeared. His mother had willingly surrendered him to his dad. The two of them had been pretty happy together until his dad died. Julian’s high school years had been spent with his mom, who seemed to have no idea what to do with him.

He didn’t have a cell phone. He was, like, one of the last humanoids on the planet who didn’t have one. That was how broke he and his mom were. She was out of work again, and he had an after-school job at a car dealership, rotating tires and changing oil. Sometimes guys gave him tips, never the rich guys with the hot cars, but the workers with their Chevys and pickups. His mom had a mobile phone, which she claimed she needed in case she got called for an acting job, but the last thing they could handle was one more bill. Their phone service at the house was so basic, they didn’t even have voice mail.

At the library, he could surf the web and access his free email. He quickly found the ROTC site and used the special log-in provided in his welcome packet, feeling as though he’d gained membership to a secret club. Then he quickly checked his email. That was how he kept in touch with Daisy. They weren’t the best at corresponding, and there was nothing from her today. He had school and work; she’d recently moved from New York City to the small town of Avalon to live with her dad. She said her family situation was weird, what with her parents splitting up. He felt bad for her, but couldn’t offer much advice. His folks had never been together, and in a way, maybe that was better, since there was no breakup to adjust to.

Email only went so far, though. He wanted to call her with his news. And to thank her for reminding him college wasn’t out of his reach. Her suggestion, made last summer, had taken root in Julian. There was a way to have the kind of life he’d only dreamed about. In a casual, almost tossed-off remark, she had handed him a golden key.

The apartment he shared with his mother was in a depressing faux-adobe structure surrounded by weedy landscaping and a parking lot of broken asphalt. He let himself in; his mom wasn’t around. When she was out of work, she tended to spend most of her time on the bus to the city, going to networking meetings.

Julian paced back and forth in front of the phone. He finally got up the nerve to call Daisy. He wanted to hear her voice and tell her in person about the letter. The call was going to add to a cost he already couldn’t afford, but he didn’t care.

She picked up right away; she always did when he called her on her cell phone because nobody else called her from this area code. “Hey,” she said.

“Hey, yourself. Is this a good time?” he asked, thinking about the three-hour time difference. In the background of the call, he could hear music.

“It’s fine.” She hesitated, and he recognized the song—“Season of Loving” by the Zombies. He hated that song.

“Everything all right?” It was weird, he hadn’t seen her since last summer, but her It’s fine struck him as all wrong. “What’s up?” he asked.

She killed the music. “Olivia asked me to be in her wedding.”

“That’s cool, right?” Julian was going to be in the wedding, too, because his brother was the groom. He’d never attended a wedding before, but he couldn’t wait because it was going to take place in August at Camp Kioga. Suddenly it occurred to him to check his ROTC schedule to make sure he was free that day.

“It’s not so cool,” Daisy said, her voice kind of thin-sounding. “Listen, Julian, I’ve been trying to figure out how to tell you something. God, it’s hard.”

His mind raced. Was she sick? Sick of him? Did she want him to quit calling, make himself scarce? Did she have a boyfriend, for Chrissake?

“Then tell me.”

“I don’t want you to hate me.”

“I could never hate you. I don’t hate anybody.” Not even the drunk driver who had hit his dad. Julian had seen the guy in a courtroom. The guy had been crying so hard he couldn’t stand up. Julian hadn’t felt hatred. Just an incredible, hollow sense of nothingness. “Seriously, Daze,” he said. “You can tell me anything.”

“I hate myself,” she said, her voice low now, trembling.

The phone wasn’t cordless, so his pacing was confined to a small area in front of a window. He looked out at the colorless February day. Down in the parking lot, Rojelio’s wife was bringing in groceries, bag after bag of them. Normally, Julian would run down and give her a hand. She had a bunch of kids—he could never get an accurate count—who ate like a swarm of locusts. All she did was work, buy groceries and fix food.