По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

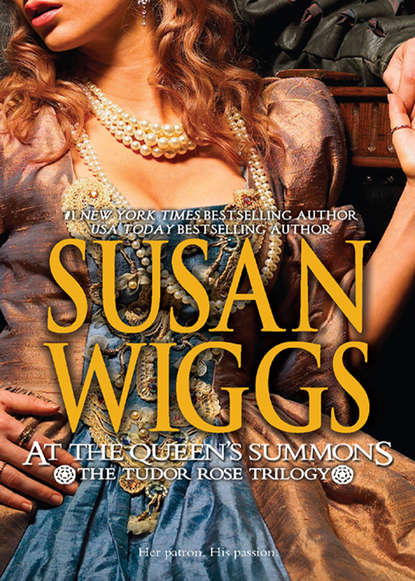

At The Queen's Summons

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

His loins burned with the image, and he gritted his teeth. The last thing he had expected was that he might desire her. Pippa lifted her arms and held them steady while he unlaced the bodice.

It proved to be the most excruciating exercise in self-restraint he had ever endured. Somehow, the dust and ashes of her harsh life had masked an uncounted wealth of charms. He had the feeling that he was the first man to see beneath the grime and ill-fitting clothes.

As he pulled the laces through, his knuckles grazed her. The maids had provided neither shift nor corset. All that lay between Pippa’s sweet flesh and his busy hands was a chemise of wispy lawn. He could feel the heat of her, could smell the clean, beeswaxy fragrance of her just washed skin and hair.

Setting his jaw with manly restraint, he turned the bodice right side up and brought it around her. As he slowly laced the garment, watching the stiff buckram close around a narrow waist and then widen over the subtle womanly flare of her hips, pushing up her breasts, he could not banish his insistent desire.

True to her earlier observation, her bosom swelled out over the top with frank appeal, barely contained by the sheer fabric of the chemise. He could see the high, rounded shapes, the rosy shadows of the tips, and for a long, agonizing moment all he could think of was touching her there, tenderly, learning the shape and weight of her breasts, burying his face in them, drowning in the essence of her.

A roaring, like the noise of the sea, started in his ears, swishing with the quickening rhythm of his blood. He bent his head closer, closer, his tongue already anticipating the flavor of her, his lips hungry for the budded texture. His mouth hovered so close that he could feel the warmth emanating from her.

She drew in a deep, shuddering breath, and the movement reminded him to think with his brain—even the small part of it that happened to be working at the moment—not with his loins.

He was the O Donoghue Mór, an Irish chieftain who, a year before, had given up all rights to touch another woman. He had no business dallying with—of all things—a Sassenach vagabond, probably a madwoman at that.

He forced himself to stare not at the bodice, but into her eyes. And what he saw there was more dangerous than the lush curves of her body. What he saw there was not madness, but a painful eagerness.

It struck him like a slap, and he caught his breath, then hissed out air between his teeth.

He wanted to shake her. Don’t show me your yearning, he wanted to say. Don’t expect me to do anything about it.

What he said was, “I am in London on official business. I will return to Ireland as soon as I am able.”

“I’ve never been to Ireland,” she said, an ember of unbearable hope glowing in her eyes.

“These days, it is a sad country, especially for those who love it.” Sad. What a small, inadequate word to describe the horror and desolation he had seen—burned-out peel towers, scorched fields, empty villages, packs of wolves feeding off the unburied dead.

She tilted her head to one side. Unlike Aidan, she seemed perfectly comfortable with their proximity. A suspicion stung him. Perhaps it was nothing out of the ordinary for her to have a man tugging at her clothing.

The idea stirred him from his lassitude and froze the sympathy he felt for her. He made short, neat work of trussing her up, helped her slide her feet into the little shoes, then stepped back.

She ruined his hard-won indifference when she pointed a slippered toe, curtsied as if to the manner born and asked, “How do I look?”

From neck to floor, Aidan thought, like his own private dream of paradise.

But her expression disturbed him; she had the face of a cherub, filled with a trust and innocence that seemed all the more miraculous because of the hardships she must have endured living the life of a strolling player.

He studied her hair, because it was safer than looking at her face and drowning in her eyes. She lifted a hand, made a fluttery motion in the honey gold spikes. “It’s that awful?” she asked. “After I cut it all off, Mort and Dove said I could use my head to swab out wine casks or clean lamp chimneys.”

A reluctant laugh broke from him. “It is not so bad. But tell me, why is your hair cropped short? Or do I want to know?”

“Lice,” she said simply. “I had the devil of a time with them.”

He scratched his head. “Aye, well. I hope you’re no longer troubled by the little pests.”

“Not lately. Who dresses your hair, my lord? It is most extraordinary.” Brazen as an inquisitive child, she stood on tiptoe and lifted the single thread-woven braid that hung amid his black locks.

“That would be Iago. He does strange things on shipboard to avoid boredom.” Like getting me drunk and carving up my chest, Aidan thought grumpily. “I’ll ask him to do something about this mop of yours.”

He meant to reach out and tousle her hair, a meaningless, playful gesture. Instead, as if with its own mind, his palm cradled her cheek, his thumb brushing up into her sawed-off hair. The soft texture startled him.

“Will that be agreeable to you?” he heard himself ask in a whisper.

“Yes, Your Immensity.” Pulling away, she craned her neck to see over his shoulder. “There is something I need.” She hurried into the kitchen, where her old, soiled clothes lay in a heap.

Aidan frowned. He had not noticed any buttons worth keeping on her much worn garb. She snatched up the tunic and groped along one of the seams. An audible sigh of relief slipped from her. Aidan saw a flash of metal.

Probably a bauble or copper she had lifted from a passing merchant in St. Paul’s. He shrugged and went to the kitchen garden door to call for Iago.

As he turned, he saw Pippa lift the piece and press it to her mouth, closing her eyes and looking for all the world as if the bauble were more precious than gold.

From the Annals of Innisfallen

I am old enough now to forgive Aidan’s father, yet young enough to remember what a scoundrel Ronan O Donoghue was. Ah, I could roast for eternity in the fires of my unkind thoughts, but there you are, I hated the old jackass and wept no tears at his wake.

He expected more of his only son than any man could possibly give—loyalty, honor, truth, but most of all blind, stupid obedience. It was the one quality Aidan lacked. It was the one thing that could have saved the father, niggardly lout that he was, from dying.

For certain, Aidan thinks on that often, and with a great, seizing pain in his heart.

A pitiful waste if you ask me, Revelin of Innisfallen. For until he lets go of his guilt about what happened that fateful night, Aidan O Donoghue will not truly live.

—Revelin of Innisfallen

Three

“So after my father’s ship went down,” Pippa explained blithely, “his enemies assumed he had perished.” She sat very still on the stool in the kitchen garden. The smell of blooming herbs filled the spring air.

“Naturally,” Iago said in his dark honey voice. “And of course, your papa did not die at all. Even as we speak, he is attending the council of Her Majesty the queen.”

“How did you know?” Beaming, Pippa twisted around on her stool to look up at him.

Framed by the nodding boughs of the old elm tree that shaded the garden path, he regarded her with tolerant interest, a comb in his hand and a gentle compassion in his velvety black eyes. “I, too, like to invent answers to the questions that keep me awake at night,” he said.

“I invent nothing,” she snapped. “It all happened just as I described it.”

“Except that the story changes each time you encounter someone new.” He spoke with mild amusement, but no accusation. “Your father has been pirate, knight, foreign prince, soldier of fortune and ratcatcher. Oh. And did I not hear you tell O Mahoney you were sired by the pope?”

Pippa blew out a breath, and her shoulders sagged. A raven cackled raucously in the elm tree, then whirred off into the London sky. Of course she invented stories about who she was and where she had come from. To face the truth was unthinkable. And impossible.

Iago’s touch was soothing as he combed through her matted hair. He tilted her chin up and stared at her face-on for a long moment, intent as a sculptor. She stared back, rapt as a dreamer. What a remarkable person he was, with his lovely ebony skin and bell-toned voice, the fierce, inborn pride he wore like a mantle of silk.

He closed one eye; then he began to snip with his little crane-handled scissors, the very ones she had been tempted to steal from a side table in the kitchen.

As Iago worked, he said, “You tell the tales so well, pequeña, but they are just that—tales. I know this because I used to do the same. Used to lie awake at night trying to put together the face of my mother from fragments of memory. She became every good thing I knew about a mother, and before long she was more real to me than an actual woman. Only bigger. Better. Sweeter, kinder.”

“Yes,” she whispered past a sudden, unwelcome thickness in her throat. “Yes, I understand.”

He twisted a few curls into a soft fringe upon her brow. The breeze sifted lightly through them. “If you were an Englishman, you would be the very rage of fashion. They call these lovelocks. They look better on you.” He winked. “A dream mother. It was something I needed at a very dark time of my life.”