По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

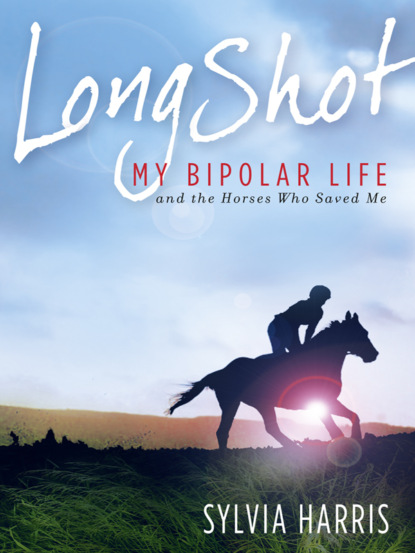

Long Shot: My Bipolar Life and the Horses Who Saved Me

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

We stand there, silently admiring the horse, who moves closer to make sure he has our attention. The suspense is killing me: Why are we here? I look at my father, who just smiles and intentionally looks away. I look back at the horse, who is now snorting, his head bobbing up and down. Is he trying to tell me something? I wonder.

Finally, the man who looks like a cowboy says to my father, “You going to let her know?” I quickly look toward my dad. He seems to be mulling it over. I can take it no longer.

“Daddy! Is he for me?”

“Hmm. Could be.”

“Stop teasing her,” said the cowboy, “and let her get up on her very own horse.”

I scream and hug my daddy. “Thank you, thank you, Daddy. What’s his name?”

“Laredo,” replied the cowboy. “He’s a quarter horse.” I didn’t care what he was; I just knew he was mine.

Daddy and the horse that got away with me on it (Sylvia Harris)

For the next few months, I couldn’t wait for each school day to end so I could bike to a stable not too far away and bond with my Laredo. I was sure he spent all day just waiting for me to show up and tell him all about my boring day at school. It didn’t hurt that I sometimes would bring carrots for him.

One day I raced to the stable, as usual, only to find that Laredo was gone. No one at the stables had an answer for me, so I biked home as fast as I could. I found my mother cooking dinner and begged her to tell me what had happened to Laredo. She wouldn’t talk about it, and told me to speak to Dad. I discovered my father had sold Laredo. It was too expensive to take care of him. My father suddenly needed the money, which I couldn’t understand. After all, my family was living the American dream on a quiet cul-de-sac in Santa Rosa. I took piano and dance lessons and went water skiing. I thought if we just got rid of all of those lessons, there would be more than enough money to take care of Laredo. I begged my father to get Laredo back, but he turned a deaf ear.

“Horses aren’t important,” he told me. “Go do your school-work and stop bothering me about this nonsense.”

I went to my mother, hoping she might influence my dad. “Can’t you get Daddy to change his mind? Please, Mom. I won’t need any Christmas or birthday presents—ever,” I said.

“Your father knows best, Sylvia,” which was code for they weren’t speaking. I may have only been twelve turning thirteen, but I knew my parents barely talked to each other. There always seemed to be something going on between them. My mother was little, like me, and hadn’t been healthy for years. She had Crohn’s disease, a chronic, episodic, inflammatory bowel disease that at times caused her great pain and forced her to undergo several surgeries. At one point, she even went down to seventy pounds and couldn’t lift herself out of the bed. My baby brother and I would try to help, but most of the load fell to my father, and he seemed to resent it.

There was nothing left for me to do about losing my horse but to cry on the shoulder of my best friend, Gidget. Yes, that was really her name—Gidget Harding—and she lived across the street from me. Where I lived was truly a slice of American idealism. And even though we were the only African American family around, everyone was friendly and supportive and race never seemed to be a factor. Not only did I cry on Gidget’s shoulder but also on her lavender-flowered bedspread and the teen magazines she tried to show me to get my mind off of losing Laredo. Before long she was crying too, and we consoled each other by promising to one day get our own horses. We then calmed down and began to think of names for the horses we would have one day.

“Alice,” she suddenly blurted out.

I told her that was kind of a plain name for a horse.

“No,” she said. “I’m talking about Alice Patterson. She lives on a farm. They must have horses. Maybe she’ll let us ride them.”

My excitement over this idea brushed away the sadness I was feeling, and we immediately called Alice. The next few months I consoled myself with visits to Alice’s farm, where there were beautiful working horses. The three of us were like Charlie’s Angels on horseback. We would ride bareback through the farmlands by her house. “I’m sliding off! I’m sliding off!” I would cry, but I never did. Riding always came naturally to me.

It was only a few times that we got to ride the horses at Alice’s. They were needed for other duties. Eventually, my parents tired of me hounding them about another horse. To divert my pleading, they made me take ice-skating, piano, and dance lessons. I enjoyed the diversions, but I never stopped longing for a horse.

I was always athletic and enjoyed sports. I became quite the star in gymnastics and track, winning meets and even participating in the state championships. The competition and success I had helped to distract me from the growing tension between my parents. The strain of my mother’s illness and her needs were taking a toll on their relationship. Always a heavy drinker, my father began to indulge more and more. Violent arguments between my parents soon became standard fare.

“Did you fall and get those bruises, Evaliene?” he would ask innocently the next morning while she cooked him breakfast. She’d nod dutifully and serve up his bacon and eggs. I sort of knew what was going on but never fully acknowledged it, preferring a loose sort of denial. As an adult, I now know that when he hit my mother, he was in an alcoholic blackout, but as a child it threw me. Not just his questions about what had happened, but the way these periodic outbursts—coming after days of binge drinking—contrasted with the life we projected to those around us … just a normal middle-class family.

We made the most of the natural splendor unique to Northern California. We would escape to the local parks and lakes for waterskiing or camping. It was hard for my mother to travel with us when she was ill, but somehow the four of us would drive to Lake Tahoe for mini holidays. On those vacations, as we sat at restaurants, we seemed like a regular, normal family enjoying each other’s company. For a few days, we would play the roles of loving husband, father, daughter, and son. But there were still few signs of affection between Mom and Dad. I rarely saw them holding hands, and hugs were not the norm for any of us.

I liked school but became a bit of a loner. Except for class or participating in school activities, like track, I wasn’t very outgoing. Even my relationship with Gidget and Alice waned. I felt more comfortable around my pets—dog, cat, whatever creature I might be befriending at the time—than around other kids. My place of choice at home was in my room, reading or doing experiments with my chemistry kit.

All that came to an abrupt halt when I turned sixteen.

Senior year pep squad (Sylvia Harris)

I decided to ditch the quiet Sylvia and became a cheerleader. Blame my hormones—I was no different from the other girls who were really getting into boys and the requisite trouble that often follows those first brushes of freedom and young love. I’d sneak alcohol out of the cabinet and join some of my fellow cheerleaders at one of their homes that would be parent-free for most of the night. We’d put on some loud Pat Benatar music and have our version of a wild evening. As Pat crooned, “Hit me with your best shot,” I even tried my first hits of pot, but back then I wasn’t a big fan of drugs. It only made me sleepy.

My drug of choice was going to the Bay Meadows Golden Gate Fields with my father when the horses were racing. I’d sit in those metal stands and feel the thunder and the power of the Thoroughbred racehorses. I was a runner and they were runners, so I identified with their every step. With my mouth wide open, I’d watch them sail through the air and silently wish I could be their rider so I could feel weightless and free.

I kept up the partying for the rest of high school, getting smashed on alcohol just about every weekend. My parents would give me the occasional lecture, and a couple of times I got in trouble for leaving without telling them; I would just look them in the face and lie.

“I didn’t do it,” I’d say in my most casual of voices. “I was home the entire time.”

“Sylvia, I checked your bedroom. You were gone,” my mother said.

“I was in the other room,” I’d fib with a straight face, and most of the time my mother would just sigh and give up. She was too sick to really delve into my problems, and my parents remained on extreme edge with each other, which left them little time for dealing with adolescent concerns. Eventually, I got the attention I thought I deserved from a pretty serious boyfriend who was the handsome, charismatic star football player at the rival school in town.

Broad-shouldered and sweet, Dan was a year ahead of me, and when he graduated, he signed up for the marines. We had the summer together before he had to take off. The night before he left, he took me in his arms. “Wait for me, Sylvia,” he pleaded.

I promised that I would, if we could get married and start our own family. The idea of my own home and a husband seemed blissful to me; I could leave the escalating baggage behind and be a part of a real family.

Deeply in love and planning my future, I’d run to the mailbox each day for his daily letter from boot camp, and I missed him in the way you only can with a first love. That fall, my senior year, I was nominated for homecoming queen. The one problem was, I didn’t have a date because my marine was off at training, and my father flatly refused to escort me.

“I’m busy that night,” was all he said. He had grown very distant and tried to spend most of his free time away from us and the house.

My last resort was asking my track coach to take me to the big dance, which was completely humiliating. To top it off, I didn’t win the crown; it was first runner-up for me. Without much enthusiasm, I had stepped onto the stage in the school gym to accept my award when my broad-shouldered, handsome ex–football star walked in like something out of a movie. It was my Dan, and now I felt like a winner. Later that night, he asked me to marry him with a beautiful diamond and emerald ring as my prize. He had to go the next day, but he more than made my night. It was enough to get me through the rest of the school year. With a happy new life awaiting me, I even buckled down and focused on my studies.

A few weeks before my high school graduation, my fiancé sent me a thicker letter, and I couldn’t wait to rip it open. I thought that maybe he had written me a few poems or enclosed a few drawings, because he liked to sketch in his free time. Instead, he sent a picture of a woman holding a baby. His baby.

Crushed, I didn’t get out of bed for the next few days. My mother tried to comfort me, but a bout of her illness was causing her to stay in bed much of the day. Eventually, this made me push aside my own misery and try to help out around the house. Dad was more distant than ever and didn’t question or show much concern for us. He would go to work, hang out, sometimes all night, and speak very little when around the house.

Having to help out more got me out of my rut, and I was determined to shake myself free from the sadness and celebrate my graduation. Even if it was not going to lead to the future I had hoped, it was still a new beginning—a fresh start. And in the days that led up to graduation, I joined my classmates in the excitement of our big event.

On graduation day the sky was a brilliant blue, and so was I, in a powder blue dress under my ceremonial black robe, replete with baby blue eye shadow to match the dress. I even had on blue high heels, and I knew I looked good.

After the ceremony, the sun was beating down on everyone, but no one really cared. I saw my father off to the side of the field. It didn’t surprise me that he wasn’t near my mother, who was sitting in the shade, with my brother fanning her. I walked over to him unsteadily, as my extremely high heels kept sinking into the turf of the football field. I thought at first he was smiling, proud to see his little girl holding her diploma and the many awards I had won for track and field. But once near him, I could see he was only squinting in the sharp sunshine.

“I can’t do this anymore,” he said as he handed me a graduation card with five hundred dollars in it. He stood there for a moment as if he were going to explain himself, but then he turned and walked away.

“Daddy?”

He didn’t stop, and I watched the wrinkled back of his tan suit as he faded away. The next day he packed up his stuff and moved back to Virginia, where we had once lived when I was very young.

What followed were really rough years where my mom was on disability and I felt myself sinking deeper into some sort of emotional abyss. It was a year later that I had my first bipolar episode.

Furlong One

The horses charge out of the starting gate, but Pegasus hesitates slightly. When horses break free they don’t all do so equally; sometimes a horse will get off to a quick start. And other times, it may seem somewhat uninterested, as if to say, “No one asked me if I felt like racing today.” This seems to be Pegasus’s mood, but maybe it’s his arthritic knees. I rubbed them frequently before the race, but it’s cold today and they could still be stiff. Hopefully, they will begin to warm up. I’m determined not to worry because I know Pegasus would sense my concern and become overly cautious. I have to run my race.

The horses bunch toward an inside position, shortening the length of the track. We are near the back, but for now that’s okay. Our time will come.

I no longer hear the announcer or the crowds cheering. All I hear is the roar of hooves pounding the surface of the cold, hard ground. The sounds and motions encapsulate me. The noise is so loud it seems to come from inside my head, but that’s okay. I’m used to hearing all kinds of things in my head. That started long ago.

Santa Rosa, California