По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

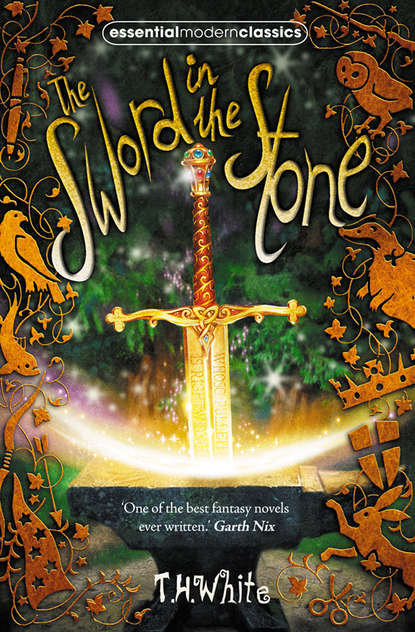

The Sword in the Stone

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Lord,” said Merlyn, not paying any attention to his nervousness. “I have brought a young professor who would learn to profess.”

“To profess what?” inquired the King of the Moat slowly, hardly opening his jaws and speaking through his nose.

“Power,” said the tench.

“Let him speak for himself.”

“Please,” said the Wart, “I don’t know what I ought to ask.”

“There is nothing,” said the monarch, “except the power that you profess to seek: power to grind and power to digest, power to seek and power to find, power to await and power to claim, all power and pitilessness springing from the nape of the neck.”

“Thank you,” said the Wart.

“Love is a trick played on us by the forces of evolution,” continued the monster monotonously. “Pleasure is the bait laid down by the same. There is only power. Power is of the individual mind, but the mind’s power alone is not enough. The power of strength decides everything in the end, and only Might is right.

“Now I think it is time that you should go away, young master, for I find this conversation excessively exhausting. I think you ought to go away really almost at once, in case my great disillusioned mouth should suddenly determine to introduce you to my great gills, which have teeth in them also. Yes, I really think you ought to go away this moment. Indeed, I think you ought to put your very back into it. And so, a long farewell to all my greatness.”

The Wart had found himself quite hypnotized by all these long words, and hardly noticed that the thin-lipped tight mouth was coming closer and closer to him all the time. It came imperceptibly, as the cold suave words distracted his attention, and suddenly it was looming within an inch of his nose. On the last sentence it opened, horrible and vast, the thin skin stretching ravenously from bone to bone and tooth to tooth. Inside there seemed to be nothing but teeth, sharp teeth like thorns in rows and ridges everywhere, like the nails in labourers’ boots, and it was only at the very last second that he was able to regain his own will, to pull himself together, recollect his instructions and to escape. All those teeth clashed behind him at the tip of his tail, as he gave the heartiest jack-knife he had ever given.

In a second he was on dry land once more, standing beside Merlyn on the piping drawbridge, panting in all his clothes.

CHAPTER SIX (#ulink_bc8c5a0c-111c-5d95-95ff-6649d76fc43e)

One Thursday afternoon the boys were doing their archery as usual. There were two straw targets fifty yards apart, and when they had shot their arrows at the one, they had only to go to it, collect them, and fire back at the other after facing about. It was still the loveliest summer weather, and there had been chickens for dinner, so that Merlyn had gone off to the edge of the shooting-ground and sat down under a tree. What with the warmth and the chickens and the cream he had poured over his pudding and the continual repassing of the boys and the tock of the arrows in the targets – which was as sleepy to listen to as the noise of a lawn-mower – and the dance of the egg-shaped sunspots between the leaves of his tree, the aged magician was soon fast asleep.

Archery was a serious occupation in those days. It had not yet been relegated to Red Indians and small boys, so that when you were shooting badly you got into a bad temper, just as the wealthy pheasant shooters do today. Kay was shooting badly. He was trying too hard and plucking on his loose, instead of leaving it to the bow.

“Oh, come on,” said Kay. “I’m sick of these beastly targets. Let’s have a shot at the popinjay.”

They left the targets and had several shots at the popinjay – which was a large, bright-coloured artificial bird stuck on the top of a stick, like a parrot – and Kay missed these also. First he had a feeling of “Well, I will hit the filthy thing, even if I have to go without my tea until I do it.” Then he merely became bored.

The Wart said, “Let’s play Rovers then. We can come back in half an hour and wake Merlyn up.”

What they called Rovers consisted of going for a walk with their bows and shooting one arrow each at any agreed mark which they came across. Sometimes it would be a mole hill, sometimes a clump of rushes, sometimes a big thistle almost at their feet. They varied the distance at which they chose these objects, sometimes picking a target as much as 120 yards away – which was about as far as these boys’ bows could carry – and sometimes having to aim actually below a close thistle because the arrow always leaps up a foot or two as it leaves the bow. They counted five for a hit, and one if the arrow was within a bow’s length, and added up their scores at the end.

On this Thursday they chose their targets wisely, and, besides, the grass of the big field had been lately cut. So they never had to search for their arrows for long, which nearly always happens, as in golf, if you shoot ill-advisedly near the hedges or in rough places. The result was that they strayed further than usual and found themselves near the edge of the savage forest where Cully had been lost.

“I vote,” said Kay, “that we go to those buries in the chase, and see if we can get a rabbit. It would be more fun than shooting at these hummocks.”

They did this. They chose two trees about a hundred yards apart, and each boy stood under one of them, waiting for the conies to come out again. They stood very still, with their bows already raised and arrows fitted, so that they would make the least possible movement to disturb the creatures when they did appear. It was not difficult for either of them to stand thus, for the very first test which they had had to pass in archery was standing with the bow at arm’s length for half an hour. They had six arrows each and would be able to fire and mark them all, before they needed to frighten the rabbits back by walking about to collect. An arrow does not make enough noise to upset more than the particular rabbit that it is shot at.

At the fifth shot Kay was lucky. He allowed just the right amount for wind and distance, and his point took a young coney square in the head. It had been standing up on end to look at him, wondering what he was.

“Oh, well shot!” cried the Wart, as they ran to pick it up. It was the first rabbit they had ever hit, and luckily they had killed it dead.

When they had carefully gutted it with the little hunting knife which Merlyn had given – in order to keep it fresh – and passed one of its hind legs through the other at the hock, for convenience in carrying, the two boys prepared to go home with their prize. But before they unstrung their bows they used to observe a ceremony. Every Thursday afternoon, after the last serious arrow had been fired, they were allowed to fit one more nock to their strings and to discharge the arrow straight up in the air. It was partly a gesture of farewell, partly of triumph, and it was beautiful. They did it now as a salute to their first prey.

The Wart watched his arrow go up. The sun was already westing towards evening, and the trees where they were had plunged them into a partial shade. So, as the arrow topped the trees and climbed into sunlight, it began to burn against the evening like the sun itself. Up and up it went, not weaving as it would have done with a snatching loose, but soaring, swimming, aspiring towards heaven, steady, golden and superb. Just as it had spent its force, just as its ambition had been dimmed by destiny and it was preparing to faint, to turn over, to pour back into the bosom of its mother earth, a terrible portent happened. A gore-crow came flapping wearily before the approaching night. It came, it did not waver, it took the arrow. It flew away, heavy and hoisting, with the arrow in its beak.

Kay was frightened by this, but the Wart was furious. He had loved his arrow’s movement, its burning ambition in the sunlight, and besides it was his best arrow. It was the only one which was perfectly balanced, sharp, tight-feathered, clean-nocked, and neither warped nor scraped.

“It was a witch,” said Kay.

“I don’t care if it was ten witches,” said the Wart. “I am going to get it back.”

“But it went towards the Forest.”

“I shall go after it.”

“You can go alone, then,” said Kay. “I’m not going into the Forest Sauvage, just for a putrid arrow.”

“I shall go alone.”

“Oh, well,” said Kay. “I suppose I shall have to come too, if you’re so set on it. And I bet we shall get nobbled by Wat.”

“Let him nobble,” said the Wart, “I want my arrow.”

They went in the Forest at the place where they had last seen the bird of carrion.

In less than five minutes they were in a clearing with a well and a cottage just like Merlyn’s.

“Goodness,” said Kay, “I never knew there were any cottages so close. I say, let’s go back.”

“I just want to look at this place,” said the Wart. “It’s probably a wizard’s.”

The cottage had a brass plate screwed on the garden gate. It said:

MADAME MIM, B.A. (Dom-Daniel)

PIANOFORTE

NEEDLEWORK

NECROMANCY

No Hawkers,

Circulars or Income Tax

Beware of the Dragon

The cottage had lace curtains. These stirred ever so slightly, for behind them there was a lady peeping. The gore-crow was standing on the chimney.

“Come on,” said Kay. “Oh, do come on. I tell you, she’ll never give it back.”

At this point the door of the cottage opened suddenly and the witch was revealed standing in the passage. She was a strikingly beautiful woman of about thirty, with coal-black hair so rich that it had the blue-black of the maggot-pies in it, sky bright eyes and a general soft air of butter-wouldn’t-melt-in-my-mouth. She was sly.

“How do you do, my dears,” said Madame Mim. “And what can I do for you today?”