По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

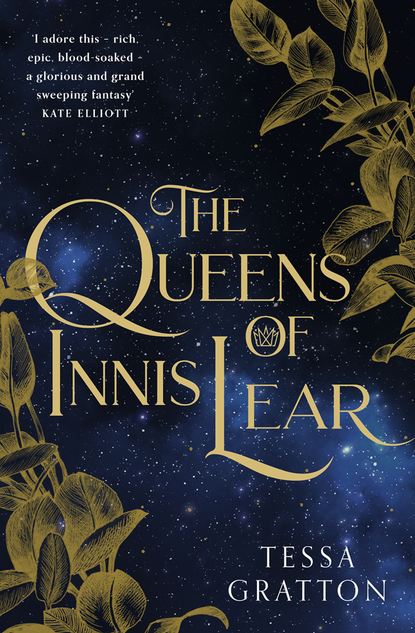

The Queens of Innis Lear

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Is that the sort of husband you want? The sort who buys you?”

She angled her head to meet his gaze. “I don’t know Aremoria at all.”

“He has the more certain reputation.”

“But certain of what?” she asked, almost to herself.

Kayo smiled grimly and offered his arm. She took it, and together they went to the high table. Elia introduced Kayo to Aremoria and Burgun, and her uncle effortlessly launched into a tale of the last time he’d passed through the south of Aremoria, on his way home from the Third Kingdom.

Able to relax somewhat, Elia picked at the meat and baked fruit in the shared platter before her, sipping pale, tart wine. She listened to the conversation of the surrounding men, smiling and occasionally adding a word. But her gaze tripped away, to the people arrayed before her, who seemed boisterous and happy.

The Earls Errigal, Glennadoer, and Bracoch sat together, the latter two both with their wives, and Bracoch’s young son gulping his drink. A familiar head leaned out of her line of sight behind Errigal, just before she could identify him.

It might’ve been the drink, but Elia felt overwhelmingly as though this bubble of friendliness would burst soon, bleeding all over her island.

Or it might have been that she herself would burst, from striving to contain her worries and loneliness, from longing for inner tranquility in the face of roiling, wild emotions. How did her sisters do it, maintain their granite poise and elegant strength? Was it because they had each other, always?

Elia had never known her sisters not to present a united front. Gaela had been deathly ill for three whole weeks just before she married, and Regan had nursed her alone through the worst of it. When Regan had lost her only child as a tiny month-old baby, Gaela had broken horses to get to her, and let no one blame Regan, let no one say a word against her sister. Elia remembered being pushed from the room, not out of anger or cruelty, but because Gaela and Regan forgot her so completely in their grief and intimacy. There was simply no place for her. Though, like tonight, they did sometimes push her out on purpose.

The first time had been the morning their mother died.

After being refused by her sisters tonight, Elia had gone to Lear. He’d opened the barred door to the sound of her voice, only to stare in horror and confusion. “Who are you?” he’d hissed, before shutting the door again. Right in her face.

Who are you?

Elia wanted to scream that she did not know.

She lifted her wine and used the goblet to cover the deep, shaking breath she took, full of the tart smell of grapes.

This was worse, more uncertain, than she’d ever seen her father. Perhaps if she’d not decided to continue her studies this spring at the north star tower, and instead had remained at his side after the winter at Dondubhan, he would not be so troubled. Perhaps if her sisters bothered to care, they could help. Or at least listen to her!

Dalat, my dear.

Had Lear expected his wife tonight, not his youngest daughter? Was he completely mad?

She should ask the stars, or even—perhaps—slip out to the Rose Courtyard again, and try to touch a smear of rootwater from the well to her lips. Would the wind have any answers?

The Earl Errigal slammed his fist on the table just below Elia, jolting her out of her traitorous thoughts. Errigal was arguing ferociously with the lady Bracoch, and then Elia’s eyes found the person she’d missed in her earlier agitation.

Older, stronger, different, but that bright gaze held the same intense promise. It was him.

Ban.

Ban Errigal.

An answer from the island to her unasked questions.

He was dressed like a soldier, in worn leather and breeches and boots, quilted blue gambeson, a sword hanging in a tired sheath. Taller than her, she was certain, despite his seat on the low bench. He never had been tall, before. His black hair, once long enough to braid thickly back, was short, slicked with water that dripped onto his collar. His tan skin was roughened by sun, and stars knew what else, from five years away in a foreign war, his brow pinched and his countenance stormy.

How could his return not have been in her star-patterns? They must have been screaming it, surely—or had it been there, hiding behind some other prophecy? Twined through the roots of the Tree of Birds? Had she missed it because all her focus had been on Lear and the impending choices about her family’s future? Had she refused to see?

Over the years she’d forcibly rejected even Ban’s name from her thoughts. Easy to imagine she’d missed some sign of his homecoming.

What else had she missed?

Elia was staring, and she realized with an embarrassed shock that he was very attractive. Not like his brother, Rory, who took after their blocky, striking father, but like his mother. There was a feral glint to his eyes, like fine steel or a cat in the nighttime. She wanted to know everything behind that look, everything about where he’d been, what he’d done. His adventures, or his crimes. Either way, she wanted to know him as he was now.

Ban Errigal noticed her looking, and he smiled.

Light flickered in Elia’s heart, and she wondered if he still talked to trees.

Her breath rushed out, nearly forming whispered words that only he would understand, of all the folk in this hot, bright hall.

But she did not know him, not anymore. They were grown and distant as stars from wells. And Elia had her place under her father’s rule; she understood her role, and how to play it. So she averted her gaze and sipped her wine, reveling silently in the feel of sunshine inside her for the first time in a long while:

Ban was home.

THE FOX (#ulink_c48b7fa9-727d-5ef1-a6b8-fbc2cd24b838)

AT THE HIGHEST rampart of the Summer Seat, a wizard listened to the wind. He sighed whispered words of his own, in the language of trees, but the salt wind did not reply.

He ought to have remembered the cadence here, the slight trick of air against air, of hissing wind through stone, skittering through leaves, but it was difficult to concentrate.

All he could think was Elia.

ELEVEN YEARS AGO, (#ulink_9c0f5321-33c8-51a4-800a-a97bc379a457)

INNIS LEAR (#ulink_9c0f5321-33c8-51a4-800a-a97bc379a457)

THE QUEEN WAS dead.

And dead a whole year tonight.

Kayo had not slept in three days, determined to arrive at the memorial ground for the anniversary. He’d traveled nearly four months from the craggy, stubbled mountains beyond the far eastern steppe, over rushing rivers to the flat desert and inland sea of the Third Kingdom, past lush forests and billowing farmland, through the bright expanse of Aremoria, across the salty channel, and finally returned to this island Lear. The coat on his back, the worn leather shoes, the headscarf and tunic, woolen pants, wide sack of food, his knife, and the rolled blanket were all he had come with, but for a small clay jar of oil. This last he would burn for the granddaughter of the empress.

Dalat.

Her name was strong in his mind as he pushed aside branches and shoved through the terrible shadows of the White Forest of Innis Lear, but her voice … that he could not remember. He’d not heard it in five years, since he left to join his father’s cousins on a trade route that spanned east as far as the Kingdom knew. Dalat had been his favorite sister, who’d raised him from a boy, and he’d promised to come back to her when he finished his travels.

He’d kept his promise, but Dalat would never know it.

Wind blew, shaking pine needles down upon him; each breath was crisp and evergreen in his throat. Every step ached; the line of muscles between his shoulders ached; his thighs and cracking knees ached; his temples and burning eyes, too. He was so tired, but he was nearly there. To the Star Field, they called it, the royal memorial ground of Innis Lear, in the north of the island near the king’s winter residence.

First Kayo had to get through the forest. God bless the fat, holy moon, nearly full and bright enough to pierce the nightly canopy and show him the way.

It seemed he had stumbled onto a wild path: wide enough for a mounted rider, and Kayo recalled the deer of the island being sturdier than the scrawny, fast desert breeds. He’d hunted them, riding with a young earl named Errigal and an unpleasant old man named Connley. They’d used dogs. His sister had loved the dogs here.

Dalat, he thought again, picturing her slow smile, her spiky eyelashes. She’d been the center of his world when Kayo was here, adrift in this land where the people were as pale as their sky. Dalat had made him belong, or made him feel so at least, when their mother sent him here because she had no use for boys, especially ones planted by a second husband. Dalat had smelled like oranges, the bergamot kind. He always bought orange-flower liqueur when he found it now, to drink in her honor.