По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

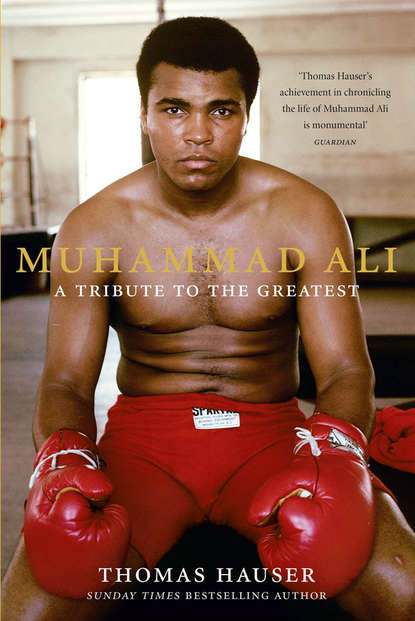

Muhammad Ali: A Tribute to the Greatest

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Why Muhammad Ali Went to Iraq (#ulink_ee7b8c38-ddb8-5707-8c11-95c5d0ab3f71)

The Olympic Flame (#ulink_0df3206f-1386-5634-b606-f8410322faae)

Ali as Diplomat: ‘No! No! No! Don’t!’ (#ulink_c3f97fe8-0497-596b-ae29-3d9a0cf4a985)

Ghosts of Manila (#ulink_c9d50f8c-edc1-5444-8d00-5d2fa549ec2c)

Rediscovering Joe Frazier through Dave Wolf’s Eyes (#ulink_c1505f1b-9152-548f-a0c2-700e1048069d)

A Holiday Season Fantasy (#litres_trial_promo)

Muhammad Ali: A Classic Hero (#litres_trial_promo)

Elvis and Ali (#litres_trial_promo)

PART II: PERSONAL MEMORIES (#litres_trial_promo)

The Day I Met Muhammad Ali (#litres_trial_promo)

I Was at Ali–Frazier I (#litres_trial_promo)

Reflections on Time Spent with Muhammad Ali (#litres_trial_promo)

‘I’m Coming Back to Whup Mike Tyson’s Butt’ (#litres_trial_promo)

Muhammad Ali at Notre Dame: A Night to Remember (#litres_trial_promo)

Muhammad Ali: Thanksgiving 1996 – ‘I’ve Got a Lot to Be Thankful For’ (#litres_trial_promo)

Pensacola, Florida: 27 February 1997 (#litres_trial_promo)

A Day of Remembrance (#litres_trial_promo)

Remembering Joe Frazier (#litres_trial_promo)

‘Did Barbra Streisand Whup Sonny Liston?’ (#litres_trial_promo)

PART III: A LIFE IN QUOTES (#litres_trial_promo)

PART IV: LEGACY (#litres_trial_promo)

The Lost Legacy of Muhammad Ali (#litres_trial_promo)

The Long Sad Goodbye (#litres_trial_promo)

Muhammad Ali’s Ring Record (#litres_trial_promo)

About the Publisher (#litres_trial_promo)

AUTHOR’S NOTE (#u9623782f-4460-5766-89f3-d563146fc4c3)

Muhammad Ali: His Life and Times, which was published in 1991, is often referred to as the definitive account of the first fifty years of Ali’s life. This is the companion volume to that book. An earlier version was published in the United Kingdom in 2005 under the title Muhammad Ali: The Lost Legacy. At that time, it contained all of the essays and articles I’d written about Ali. Muhammad Ali: A Tribute to the Greatest contains recently authored pieces, including the previously unpublished essay, ‘The Long Sad Goodbye’.

Thomas Hauser

PART I

ESSAYS (#u9623782f-4460-5766-89f3-d563146fc4c3)

THE IMPORTANCE OF MUHAMMAD ALI (#u9623782f-4460-5766-89f3-d563146fc4c3)

(1996)

Cassius Marcellus Clay Jr, as Muhammad Ali was once known, was born in Louisville, Kentucky, on 17 January 1942. Louisville was a city with segregated public facilities; noted for the Kentucky Derby, mint juleps, and other reminders of southern aristocracy. Blacks were the servant class in Louisville. They raked manure in the backstretch at Churchill Downs and cleaned other people’s homes. Growing up in Louisville, the best on the socio-economic ladder that most black people could realistically hope for was to become a clergyman or a teacher at an all-black school. In a society where it was often felt that might makes right, ‘white’ was synonymous with both.

Ali’s father, Cassius Marcellus Clay Sr, supported a wife and two sons by painting billboards and signs. Ali’s mother, Odessa Grady Clay, worked on occasion as a household domestic. ‘I remember one time when Cassius was small,’ Mrs Clay later recalled. ‘We were downtown at a five-and-ten-cents store. He wanted a drink of water, and they wouldn’t give him one because of his colour. And that really affected him. He didn’t like that at all, being a child and thirsty. He started crying, and I said, “Come on; I’ll take you someplace and get you some water.” But it really hurt him.’

When Cassius Clay was 12 years old, his bike was stolen. That led him to take up boxing under the tutelage of a Louisville policeman named Joe Martin. Clay advanced through the amateur ranks, won a gold medal at the 1960 Olympics in Rome, and turned pro under the guidance of The Louisville Sponsoring Group, a syndicate comprised of 11 wealthy white men.

‘Cassius was something in those days,’ his long-time physician, Ferdie Pacheco, remembers. ‘He began training in Miami with Angelo Dundee, and Angelo put him in a den of iniquity called the Mary Elizabeth Hotel, because Angelo is one of the most innocent men in the world and it was a cheap hotel. This place was full of pimps, thieves and drug dealers. And here’s Cassius, who comes from a good home, and all of a sudden he’s involved with this circus of street people. At first, the hustlers thought he was just another guy to take to the cleaners; another guy to steal from; another guy to sell dope to; another guy to fix up with a girl. He had this incredible innocence about him, and usually that kind of person gets eaten alive in the ghetto. But then the hustlers all fell in love with him, like everybody does, and they started to feel protective of him. If someone tried to sell him a girl, the others would say, “Leave him alone; he’s not into that.” If a guy came around, saying, “Have a drink,” it was, “Shut up; he’s in training.” But that’s the story of Ali’s life. He’s always been like a little kid, climbing out onto tree limbs, sawing them off behind him and coming out okay.’

In the early stages of his professional career, Cassius Clay was more highly regarded for his charm and personality than for his ring skills. He told the world that he was ‘The Greatest’, but the brutal realities of boxing seemed to dictate otherwise. Then, on 25 February 1964, in one of the most stunning upsets in sports history, Clay knocked out Sonny Liston to become heavyweight champion of the world. Two days later, he shocked the world again by announcing that he had accepted the teachings of a black separatist religion known as the Nation of Islam. And on 6 March 1964, he took the name ‘Muhammad Ali’, which was given to him by his spiritual mentor, Elijah Muhammad.

For the next three years, Ali dominated boxing as thoroughly and magnificently as any fighter ever. But outside the ring, his persona was being sculpted in ways that were even more important. ‘My first impression of Cassius Clay,’ author Alex Haley later recalled, ‘was of someone with an incredibly versatile personality. You never knew quite where he was in psychic posture. He was almost like that shell game, with a pea and three shells. You know: which shell is the pea under? But he had a belief in himself and convictions far stronger than anybody dreamed he would.’

As the 1960s grew more tumultuous, Ali became a lightning rod for dissent in America. His message of black pride and black resistance to white domination was on the cutting edge of the era. Not everything he preached was wise, and Ali himself now rejects some of the beliefs that he adhered to then. Indeed, one might find an allegory for his life in a remark he once made to fellow Olympian Ralph Boston. ‘I played golf,’ Ali reported, ‘and I hit the thing long, but I never knew where it was going.’

Sometimes, though, Ali knew precisely where he was going. On 28 April 1967, citing his religious beliefs, he refused induction into the United States Army at the height of the war in Vietnam. Ali’s refusal followed a blunt statement, voiced 14 months earlier – ‘I ain’t got no quarrel with them Vietcong.’ And the American establishment responded with a vengeance, demanding, ‘Since when did war become a matter of personal quarrels? War is duty. Your country calls – you answer.’

On 20 June 1967, Ali was convicted of refusing induction into the United States Armed Forces and sentenced to five years in prison. Four years later, his conviction was unanimously overturned by the United States Supreme Court. But in the interim, he was stripped of his title and precluded from fighting for three and a half years. ‘He did not believe he would ever fight again,’ Ali’s wife at that time, Belinda Ali, said of her husband’s ‘exile’ from boxing. ‘He wanted to, but he truly believed that he would never fight again.’

Meanwhile, Ali’s impact was growing – among black Americans, among those who opposed the war in Vietnam, among all people with grievances against The System. ‘It’s hard to imagine that a sports figure could have so much political influence on so many people,’ observes Julian Bond. And Jerry Izenberg of the Newark Star-Ledger recalls the scene in October 1970, when at long last Ali was allowed to return to the ring.

‘About two days before the fight against Jerry Quarry, it became clear to me that something had changed,’ Izenberg remembers. ‘Long lines of people were checking into the hotel. They were dressed differently than the people who used to go to fights. I saw men wearing capes and hats with plumes, and women wearing next to nothing at all. Limousines were lined up at the curb. Money was being flashed everywhere. And I was confused, until a friend of mine who was black said to me, “You don’t get it. Don’t you understand? This is the heavyweight champion who beat The Man. The Man said he would never fight again, and here he is, fighting in Atlanta, Georgia.”’

Four months later, Ali’s comeback was temporarily derailed when he lost to Joe Frazier. It was a fight of truly historic proportions. Nobody in America was neutral that night. ‘It does me good to lose about once every ten years,’ Ali jested after the bout. But physically and psychologically, his pain was enormous. Subsequently, Ali avenged his loss to Frazier twice in historic bouts. Ultimately, he won the heavyweight championship of the world an unprecedented three times.

Meanwhile, Ali’s religious views were evolving. In the mid-1970s, he began studying the Qur’an more seriously, focusing on Orthodox Islam. His earlier adherence to the teachings of Elijah Muhammad – that white people are ‘devils’ and there is no heaven or hell – was replaced by a spiritual embrace of all people and preparation for his own afterlife. In 1984, Ali spoke out publicly against the separatist doctrine of Louis Farrakhan, declaring, ‘What he teaches is not at all what we believe in. He represents the time of our struggle in the dark and a time of confusion in us, and we don’t want to be associated with that at all.’

Ali today is a deeply religious man. Although his health is not what it once was, his thought processes remain clear. He is, still, the most recognisable and the most loved person in the world.

But is Muhammad Ali relevant today? In an age when self-dealing and greed have become public policy, does a 54-year-old man who suffers from Parkinson’s syndrome really matter? At a time when an intrusive worldwide electronic media dominates, and celebrity status and fame are mistaken for heroism, is true heroism possible?

In response to these questions, it should first be noted that, unlike many famous people, Ali is not a creation of the media. He used the media in an extraordinary fashion. And certainly, he came along at the right time in terms of television. In 1960, when Cassius Clay won an Olympic gold medal, TV was crawling out of its infancy. The television networks had just learned how to focus cameras on people, build them up, and follow stories through to the end. And Ali loved that. As Jerry Izenberg later observed, ‘Once Ali found out about television, it was, “Where? Bring the cameras! I’m ready now.”’

Still, Ali’s fame is pure. Athletes today are known as much for their endorsement contracts and salaries as for their competitive performances. Fame now often stems from sports marketing rather than the other way around. Bo Jackson was briefly one of the most famous men in America because of his Nike shoe commercials. Michael Jordan and virtually all of his brethren derive a substantial portion of their visibility from commercial endeavours. Yet, as great an athlete as Michael Jordan is, he doesn’t have the ability to move people’s hearts and minds the way that Ali has moved them for decades. And what Muhammad Ali means to the world can be viewed from an ever deepening perspective today.

Ali entered the public arena as an athlete. To many, that’s significant.