По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

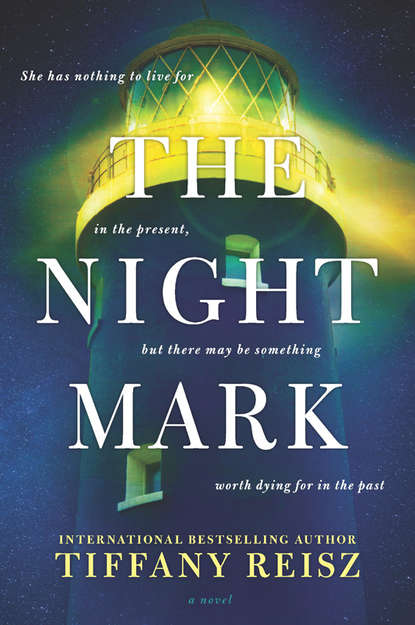

The Night Mark

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“I’m sorry,” she whispered. “I had to do it alone.”

“You were alone?”

“Yes,” Faye said. “I mean, except for a bird. There was a big white bird there, too. Maybe he knew Will.” She laughed at herself, and fresh hot tears fell from her burning eyes.

“You don’t sound good, Faye. Where are you?”

She wished he wouldn’t talk to her so gently. It made it harder to stay angry, and she needed her anger. It gave her energy.

“I don’t have to tell you that.”

“Jesus, do you think I’m going to stalk you or something? If I was obsessed with you I could have dragged the divorce out a couple years. It could have been ugly. I didn’t, though, and I don’t remember you saying thank you for that.”

“I’m supposed to thank you for not torturing me with a protracted divorce? Okay. Thank you, Hagen. Thank you very much.”

The pause between her last words and his next words was so long she thought he’d hung up on her. No such luck.

“I was never going to be Will,” Hagen said at last. “And it wasn’t fair of you to expect me to be him.”

“I never expected you to be Will, and I didn’t want you to be Will.”

“Because no one could be Will, right? Except Will, because Will was perfect.”

“Will wasn’t perfect,” Faye said slowly, as if speaking to a child. “No one is perfect. Especially not a man who left dirty dishes under the bed and never cleaned a toilet in his life. But this is what Will was—Will was the man who loved me, all of me, even though I yelled at him and called him a thoughtless child when he almost burned the house down trying to cure a baseball mitt in the oven. He cleaned the oven, he bought me flowers and he told me he was sorry. So no, Will was not perfect. Will was better than perfect. He was too good for this world. The world didn’t deserve him and neither did I.”

In the pit of the night when Faye was alone with her thoughts and her loneliness, she would tell herself that Will was too good for her. It was her only explanation for why he was taken from her. The only explanation that ever made sense.

“Hagen, I know—I do—that you thought by marrying me you were honoring Will, doing what he would have wanted you to do, doing what he would have done in your place. I thought so, too. But it was a mistake.”

“I kept you from killing yourself for nearly four years and you call that a mistake?”

Faye shrugged, shook her head and remembered the night Hagen had taken the pill bottle out of her hand. By the next day every gun, knife and pill in the house had been locked in a safe.

She didn’t have the heart to tell him half the reason she’d had that pill bottle in her hand was because she’d married him.

“Hagen, I really have to go.”

“Can I ask you one thing now that’s it’s all over? One question, one answer. I think you owe me that after four years of marriage and carrying my child and eating my food and sleeping in my bed and living in my house and taking my cock without complaint all that time.”

Faye sighed. She’d been pregnant for a mere six weeks three years ago and Hagen still talked about that lost pregnancy like she’d given birth to a living child who’d died in his arms. He’d lost children. Faye had lost herself. They couldn’t even grieve together.

“Faye?”

“Ask,” she said. “But don’t get pissed at me if you don’t like the answer.”

“Did you ever love me?”

“I tried.” Faye closed her eyes, and twin tears rolled down her cheeks, scalding hot on her cold skin. “I swear I did try.”

“So no?”

“No,” Faye said.

This time when the silence came she knew Hagen had hung up.

Faye hated this part, hated when it hit her full body like she’d been thrown against a wall and nothing could stop her from feeling everything she didn’t want to feel. Her chest ached and her face, too. Her throat tightened like a strong man’s hand was clutched around it, squeezing. Her stomach roiled like boiling water. From her feet to her guts to her heart to her eyes, she ached with pure unadulterated panic. She hadn’t had a panic attack since before Will died. But she remembered this feeling, this vise on her chest, this unbearable urge to run away, to scream, to fly and to fight. She’d tumbled headfirst into the pit, and nothing could get her out of it—not a rope or a pickax or her own bare hands clawing at the dirt walls.

She lowered her head to the steering wheel and squeezed the leather as hard as she could. In her twenties her panic attacks had been triggered by her student loan debt combined with her erratic income from freelancing. One bill could send her spiraling into the cold sweats, nausea and a sense of being choked to death by an invisible hand. Pills helped a little, but nothing helped more than Will putting her on his lap and holding her as he rubbed her back.

“Breathe, babe. In and out,” he’d say, his voice strong and calm as she gasped and swallowed air. “It’s not the end of the world. It only feels that way. We’ll just be poor,” he would say to make her smile. “We’ll live in a cabin in the middle of nowhere with no electricity or running water. We’ll smell horrible. We’ll grow our own food. We’ll have cows and chickens and no TVs. We’ll have so much free time, babe. I don’t even know what we’ll do with all that free time... Wait. I got it. Blow jobs three times a day.”

And Faye would laugh through her tears, which only Will could make her do.

“What about baseball?” she’d asked him.

“Just a game, babe. It’s just a game. You and me, we’re the real thing. Right?”

“Right.” She’d put her head back on his big broad chest and ride out the wave of her panic in his arms.

“Breathe, sweetheart,” Will would say, rocking her like a child. “I’m here, and I love you.”

But he wasn’t here anymore.

And he didn’t love her anymore.

If the dead could love, they had a terrible way of showing it.

But breathe she did—in and out—and sure enough, when she raised her head she saw people walking into the gas station, a little boy racing to beat his sister to the door so he could be the one to hold it open for their mother. A robin pecked at a rotting pretzel on the asphalt. A shiny blue Corvette with Georgia plates pulled in for a fill-up. Life. It was still happening. The world hadn’t ended. Not even her little corner of it.

Once she was back in control of her emotions, Faye started her Prius. As always she was taken aback by how quietly the car ran. She really never knew if it was running until it moved. Same with her—she didn’t know she was alive unless she was moving—so she kept moving.

The phone rang again. Hagen calling back, either to keep fighting or to apologize. She ignored the call, and she also ignored the urge to toss the phone out of the car window into Port Royal Sound.

Faye found Federal Street easily, thanks to her tourist’s map. Father Pat Cahill had said he’d be painting the marshlands, but that didn’t narrow things down much. The entire place was surrounded by marshlands. She drove to the very end of the road; if she’d kept driving she’d drive straight into the water. Although tempting—today especially—Faye imagined with her luck the car would land on a dense patch of swamp, and she’d have a few hours to wait before sinking enough to even get her feet wet. Although she couldn’t think of many good reasons to go on living, she also couldn’t think of any good reasons for dying. So she went on as most people did for want of a viable alternative.

Two beautiful old white houses stood proud and dignified on either side of Federal Street, but only one of them had a man sitting on the lawn in front of an easel. The house he painted was a grand antebellum mansion, three stories, white, red roof, green shutters and a porch one could get lost on without a map and a compass. Before leaving the car, Faye checked her face in the mirror looking for any telltale signs of her recent breakdown. The makeup was an easy fix, but she couldn’t do a thing about the redness in her eyes except hope Father Cahill didn’t notice it. She grabbed her camera bag from the backseat. Might as well get some work done while she was here.

She strode across the lawn toward him, and he turned her way and gave her a broad smile.

“Are you my new patron?” he called out. “If so, I thank you and owe you an apology.”

Faye smiled back. “No apologies necessary. The kid let me have it for twenty-five bucks.”

“Twenty-five? Highway robbery.” He rubbed his palms on his paint-smeared khaki slacks, and then held out his hand to her. She was struck by how much he looked like Gregory Peck in the late actor’s last years. Minus the mustache but still with the glasses. His black T-shirt was as paint riddled as his pants. Did he wipe his paintbrushes on his clothes?

“Thanks for meeting with me, Father Cahill.” He had a nice handshake, firm and friendly.

“Pat, please. And I’m retired, so it’s not like I have a full dance card. Pull up the stool and tell me about yourself.” He didn’t say card, he’d said cahd. She knew she was dealing with an old Boston boy. If Kennedy had lived, this was probably how he would have sounded in his seventies.