По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

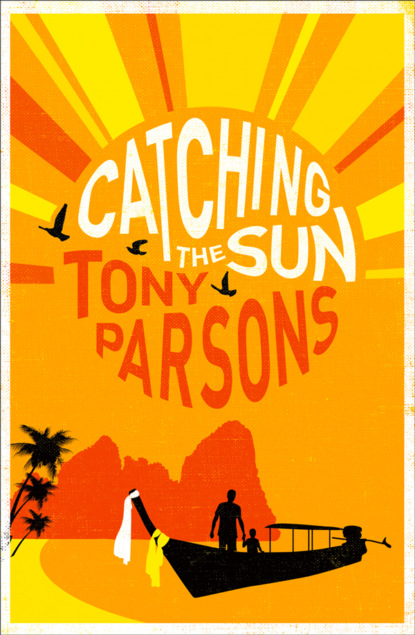

Catching the Sun

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Then, waved off by my family and watched by our curious, slightly disbelieving neighbours, I rode the Royal Enfield very carefully down the yellow-dirt-track road that had been darkened to a dirty gold by the rain, and I went to work.

The Royal Enfield made you sit upright, like a man from the past, and I still wasn’t used to it.

But as I rode to the airport, the sweep of Hat Nai Yang on my left, and the warm air full of the smells from the shacks cooking barbecued seafood on the beach, I felt Phuket wrap itself around me, and I began to feel better.

I looked out at the longtails moored on the bay, still surprised that so much of island life took place on the water, and when I turned back I saw a motorbike hurtling towards me on the wrong side of the road.

There were two young women on it, their black hair flying, their eyes hidden behind shades. The one riding pillion was sitting side-saddle, her flip-flops dangling at the end of her thin legs, smoking a cigarette, and the one who was meant to be riding the motorbike seemed to be reading a message on her phone.

I cried out and swerved and just missed them, smelling the stink of a two-stroke engine as we passed each other by inches and I fought for control of the Royal Enfield on the wet road. The motorbike rider had not even looked up. But her passenger turned and gave me a lazy smile, her teeth bone white against her shining brown face.

As I looked back, she wai-ed me.

Still smiling, still hurtling down the road, she put her hands together close to her chest and lowered her head, the sheets of black hair tumbling forward, whipping wildly in the wind. Her friend was still busy riding the motorbike and now seemed to be replying to the message. But the girl on the back gave me a wai.

In the short time we had been on the island, I had seen the classic Thai gesture every day and everywhere. The wai. I was still trying to understand it, but I didn’t think I ever would because the wai seemed to say so much.

The wai was respect. It said thank you. It said hello. It said goodbye. It said very nice to meet you.

It said – Whoops! Really sorry about nearly killing you there.

And whatever it was saying, the wai always looked like a little prayer.

The sign I held at Phuket airport said WILD PALM PROPERTIES in the top corner, with a picture of two sleepy palm trees, and then a name and a city that blurred into one. MR JIM BAXTER MELBOURNE. Standing at the airport with a sign in my hands was about the only thing that did not feel new to me, because I had done the same thing in England.

You hold your sign and you look at the crowds but you never really find them. They always find you. I watched the crowds pouring out of arrivals until a tired-looking man in his fifties with thinning fair hair was coming towards me.

‘I’m Baxter,’ he said, and I took his bags. There wasn’t much for someone who had come all the way from Australia.

As we walked to the car park I made some friendly noises about the flight but he just grunted, clearly not interested in small talk, so I kept my mouth shut. He seemed worn out, and it was more than the sleep-deprived dehydration of a long haul flight. He only really perked up when we arrived at the Royal Enfield.

‘Bloody hell,’ he said. ‘Wild Palm can’t send a car? All the business I put his way, and your boss can’t spring for a car?’

I smiled reassuringly. ‘Mr Baxter, at this time of day the bike is the quickest way to get you to our destination.’ I nodded and smiled some more. ‘And you’re perfectly safe.’

That wasn’t strictly true. Most of the foreigners who die in Thailand are either killed on motorbikes or after taking fake Viagra. It’s all that sunshine.

It does something to the head.

As we drove south, the other riders swarmed around us. Sharing food. Checking their email. Gossiping. Admiring babies. Calling mum. And all of it at sixty miles an hour. Baxter clung to my waist as the island whipped by.

We rode past walled villas and tin shacks, mosques and temples, scraps of land for sale and the lush spikes of the pineapple groves, the thick green forest of Phuket’s interior always rising above us.

On the back roads the rubber plantations went on forever – tall thin trees in lines that were so alike I realized that they could hypnotize you and tear your eyes from the road ahead if you let them. On the main roads there were giant billboards with men in uniform, advertising something unknown, smiling and saluting, soldiers where the celebrities should be.

I watched for the landmark I had been told to look out for – the big roundabout at Thalang where dark, life-sized statues of two young women stood on a marble plinth in the middle of the busy junction.

I turned left at the statues and then took a right on to a side road where a Muslim girl who was about nine years old, the same age as Keeva and Rory, bumped solemnly towards us on her motorbike, her eyes unblinking above her veil.

As the warm air touched the sweat on my face, I felt Baxter clinging to me even tighter.

I knew exactly how he felt.

It was all new to me, too.

Farren’s home came out of nowhere.

The road stuttered out into almost nothing, just this hard-packed dirt track surrounded by mangroves, making me think I must have taken a wrong turn.

Then it appeared. A development of modern houses that had been carved out of the mangrove swamp. You could see the bay beyond, and the boats in their berths at the yacht club.

We paused at the security barrier and now Baxter felt like talking.

‘Farren has done all right for himself,’ he said. ‘Your boss.’ I could feel his breath on the back of my neck. ‘Known him long, have you?’ he said.

I nodded my thanks to the security guard as the barrier came up.

‘Not long,’ I said, and it sounded strange – that I would be here on the far side of the world working for a man who I had known for just a few months. But Farren had found me in London when I was at a low and feeling that all the best times were behind me. He had seen some point to me when I was struggling to see it myself. Most important of all, when I had no work, Farren had offered me a job. ‘Long enough,’ I said.

I parked the bike in the car park and we started up the path towards the house. A pale green snake, eighteen inches long, slithered along beside me. Its head was livid red, as if it was enraged about something. I kept an eye on it. But it got no closer, and it got no further away. It was as if we were out for a stroll together. Then at the last moment, at the end of the mangroves, it slipped back into the trees.

Before I rang the bell, Farren’s man answered the door. Pirin. A short, heavy-set Thai, dark as one of the elephant mahouts. He led us inside. I had only been here a handful of times, and the beauty of Farren’s home took my breath away.

It was full of glass and air and space. But it was Thai. Handwoven rugs on gleaming hardwood floors. Claw-foot sofas and chairs carved from more hardwood. That sense of abundance, as though the world would never run out. Beyond the glass wall of the living room there was an infinity pool that seemed suspended in space. It hung above the bay like a good dream.

Farren rose from the water, his body tanned and hard, and as Pirin draped a white towel around his broad shoulders, he came towards us smiling with all his white teeth.

‘I want my money back,’ Baxter said.

The Australian was an old guy, worn out from the plane, stiff and creaky from the ride on my motorbike. His strong days were all behind him.

But once he had his hands around Farren’s throat, it took Pirin and me quite a while to pull him off.

3

I walked from Farren’s home back down to the security gate, pausing to let a flock of two-stroke bikes pass by – all the cleaners and cooks and maids coming to work, two or three of them perched on some of the bikes – and I tasted the diesel of their little machines on the back of my throat.

I watched the tribe of helpers hurrying to their work in the big white houses and it seemed strange to me, like something from a hundred years ago, a world divided into people who were servants and people who were served.

I headed down a track through the mangroves that eventually led to the bay until I came to a single-storey building with blacked-out windows. It looked like an abandoned barracks at an army base. But this was the heart of Wild Palm, and as soon as I opened the door I was hit by a barrage of noise.

A long table, covered with phones, computer screens and half-eaten food, surrounded by a dozen men and women – mostly men – all of them dressed for the beach, all of them speaking urgently into handsets – cajoling, pleading, bullying, laughing, taunting and selling – always selling. None of them were over thirty. All of them were talking English but the accents were from the US and the UK and South Africa and Australia. I walked to the far end of the room to the water cooler. Some eyes flicked my way, but they all ignored me.

I sipped from a polystyrene cup, and nodded at a young Englishman called Jesse. He was very white – his skin, his cropped hair. For someone living in the tropics, he looked as though he had never been touched by the sun. He was wearing a baggy pair of Muay Thai shorts and nothing else. He cradled the phone between his neck and shoulder as he doused a bowl of noodles in sweet chilli sauce.

‘Yeah, yeah,’ he was saying, the accent from the north of England. ‘I’m at Heathrow. Just checking into my flight for Thailand. Excuse me a second,’ he said into the phone, and then he stared at me, the pale eyes wide, as if I was someone else, in some other place. ‘Seat 1K?’ he said. ‘Oh, that will be fine. The vegetarian meal, please …’ The eyes flicked away, and I noticed that there were three watches on his thick white arm, all of them set to a different time zone. ‘Sorry about this, John,’ he said into the phone, and the eyes were on me again. ‘Do you have my Gold Executive Club Number?’ A pause. I sipped my water, trying to fit the words he was saying to the place he was in. But I saw that was impossible. ‘Oh, it’s in the system already?’ he said, eyes wide with surprise. ‘Perfect. Sorry, John – the hassle of modern travel, eh? What’s that?’ A burst of mad laughter. ‘Yeah, you’re right there – at least I’m in First Class.’ He covered the phone with his hand. ‘Don’t you have anything to do?’

‘Getting you,’ I said. ‘Bringing you to the house. That’s what I’ve got to do.’