По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

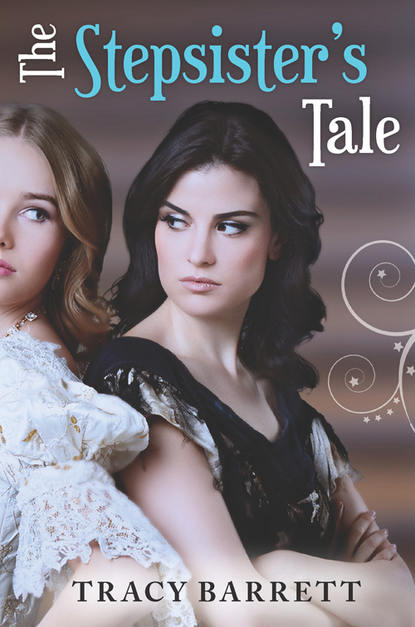

The Stepsister's Tale

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“Oh, the surprise isn’t the carriage,” Mamma said. “I mean, yes, that is our carriage now, but that’s not the surprise. The surprise is what’s in it.”

“Visitors?” Maude squeaked. Jane shrank back. Why would Mamma do this to them? What would they say to visitors? How could they receive them in their ragged dresses and bare feet and uncombed hair? She licked her finger and rubbed at her face, trying to remove the smudges that she knew she must have gotten in the barn.

“Not visitors,” Mamma said. “Something better. Something you have been wanting for a long time.” What had they been wanting? Before they could guess, Mamma told them. “A new papa, and a new little sister.”

“Oh!” breathed Maude. “A baby!” There hadn’t been a baby in the house for so long, not since Robert.

“Not exactly a baby.” Mamma looked toward the carriage. A tall, balding man stepped out of it and then turned and reached back inside, speaking in a low, coaxing tone. He was answered by a torrent of words that the girls couldn’t make out, although their meaning was clear: whoever was in the carriage was unhappy.

Mamma laid her hand on the man’s arm. “Let me try, Harry.” The man stepped back, and Mamma reached in the open door. “Come, Isabella. Come see your new home.” She stood for a moment and then moved away, helping someone out and then down the two steps.

Jane caught her breath. The small girl looked unlike anyone she had ever seen before. Her hair was of that pale brown called ash-blond, and it hung to her waist in shiny waves. Her oval face was a clear, delicate white, and she had pale pink cheeks and dainty red lips. Her sky-blue dress stopped just below her knees, showing snow-white stockings and tiny white shoes. Her hair was held back by a blue ribbon that had to be silk. She was the most beautiful thing Jane had ever seen, standing perfectly still in front of the dry stone fountain in the curve of the gravel drive. Maude whispered to Jane, “Is she real?”

“Of course she’s real, silly,” Jane whispered back. She had a sudden flash of a memory—of Papa’s mother, Grandmother Montjoy, who had died when Jane was four. Grandmother’s face had been white and wrinkled, her staring eyes unfocused, and she’d mumbled as she reached out a shriveled finger and gently stroked something—a porcelain fairy, Jane remembered, with dark gold curls and blue wings.

The man, whose thin hair was a duller version of the girl’s and whose sweat-streaked skin might once have been as perfect as hers, bent over and whispered in her ear. She crossed her arms and turned her head away from him, her lower lip sticking out and trembling.

Mamma called, “Girls, come here.” Maude looked at Jane, who could read her own reluctance mirrored in her sister’s eyes. They didn’t dare disobey, and after another moment’s hesitation, Jane walked to the carriage. Maude followed a step behind.

“Harry,” Mamma said, “these are your new daughters. This is Jane, the elder, and behind her is Maude.”

“I am happy to meet you,” the man said. He didn’t sound happy.

“Where are your curtseys, girls?” Mamma asked sharply. Startled, Jane tucked one foot behind the other and made an awkward bob. Maude did the same. It had been so long since either of them had had to perform a curtsey—Jane couldn’t remember, in fact, the last time they had met someone new—that she knew they looked ridiculous. Especially with dirty, bare feet and knots in their hair. Especially in front of that fairy princess.

The fairy princess burst out laughing, and Jane felt herself flush. “What was that?” the girl asked. “Is that how people curtsey in the country?” Maude looked as though the child had slapped her.

“Perhaps you could help them learn to do it better,” Mamma suggested. “Would you like to show them how a curtsey is done in town?”

I don’t want her to show me anything, Jane thought.

The girl picked up her skirt in the tips of her fingers, and placing her right foot behind her left, she sank down nearly to the ground, then rose smoothly, lining her two tiny feet up next to each other again. Jane suddenly felt too tall, and lumpy. Her dress had grown so tight over her chest that her breasts were flattened against her ribs, and she’d had to let out the skirt of her dress to accommodate suddenly round hips. This girl was so slender that even her small curves were graceful.

Maude reached out and touched a tawny curl that dangled past the girl’s shoulder. “You’re beautiful,” she breathed.

The girl didn’t answer, and Maude, looking embarrassed, dropped her hand.

“Take the horses into the barn and wipe them down well,” the man said to the coachman. “When I am satisfied that you have done your work properly, I will pay you.” The man, who had unharnessed the horses, made a quick bow and led them around in a tight circle and down to the barn.

Mamma held out her hand to the girl. “Come, Isabella. Have some supper and then go to bed. You’ll feel happier after you sleep. In the morning, Jane and Maude will show you all around. There might be some new puppies in the barn—are there, girls?”

“Yes, Mamma.” Maude was eager to catch Mamma up on everything that had happened in her absence. “She had eight right after you left, and only one died. There are three boys and four girls, two brown, three brown and white, two—”

“Father,” Isabella said.

“Yes, darling,” he said promptly.

“I don’t want to see puppies in the barn.”

“Then you won’t have to. There are rats in barns, anyway. Come in and have some supper now, and then I’ll put you to bed.”

“I can put her to bed,” Mamma said. “I’m her mother now.”

“Stepmother,” Isabella said. “And I want my father to put me to bed.” She clung to the man’s hand.

He looked down at her. “Of course, sweetheart. Of course.” He picked her up and carried her over the broken front steps. He stumbled over a crack and muttered something, and then set the child down at the door, which he pushed open. They followed him as his booted footsteps rang in the front hall. The sound, so familiar yet almost forgotten, made Jane’s stomach lurch.

The man came to an abrupt halt as two mice scurried into their hole in a door frame, disgust clear on his face. “My God, Margaret,” he said. His daughter pressed against his side, and he put his arm around her.

Jane knew the front hall was big—Hannah Herb-Woman’s entire hut could fit in it with room to spare—but to her it had always been just the place you had to go through to get to the living quarters. Its marble floor gleamed only when one of the girls polished an area to play a game on it, and now that these strangers were staring, she realized how dingy the stone was. The velvet drapes framing the tall doorways were tattered, and the gold tassels that fringed their edges were faded and dull. The decaying staircase loomed above them, the flaking gilt of the scrolls and curlicues along its sides glinting even in the dim light that came through the open door. The light also caught the strands of a spider web that stretched from a banister to the remains of the chandelier high on the ceiling. When Jane saw the girl wrinkling her nose, she, too, caught the odor of mold and rot.

The man glanced at Mamma. “I told you it was in need of some repair,” she said. Jane detected an uneasy note in her voice.

“I know, but I had no idea....” He shook his head. “It hasn’t been that long—only a few years.”

“The decay had started even when I was a child. My parents managed to hide the extent of it.”

“Father!” burst out the girl. “You said we were going to have supper!”

“Yes, darling.” He instantly turned to her. “Yes, of course. Where...?” He looked around.

“Oh, we don’t use much of the house,” Mamma answered vaguely. She gestured at the South Parlor. “This is where we spend most of our time. I’m afraid it’s not very presentable.” Not presentable? But they had been so proud of how they had cleaned it.

They all followed her in. Harry wrinkled his nose as he looked around. “The first thing we’ll do is get the kitchen back in working order. I won’t be comfortable in a room with the smell of cooking in it.”

“We haven’t cooked a thing all day,” Jane said indignantly. They had eaten nothing but cheese and some nuts that Maude had found.

“Girls—” Mamma began, and hearing the exhaustion in her voice, Jane leaped forward.

“Sit down, Mamma,” she said. “I’ll find something.” Maude was already heading out to the dairy, so Jane went to the pantry. She glanced at the bare shelves, hoping against all logic that somehow more food would have appeared there. Of course it hadn’t. The shelves were waiting for whatever Mamma had brought home from the market; that’s why she had gone to town. Or was it? Jane wondered, suddenly suspicious. Had Mamma really gone to meet that man?

Nonsense. They were almost out of everything. Jane poked around in one nearly empty bin and then another. Turnips, onions—no, she didn’t think Mamma wanted her to take the time to cook anything. Apples—yes, that would do for a quick supper. She filled her apron, choosing the reddest ones. Into her pocket pouch she put almost the last of the biscuits, the twice-cooked bread that lasted a long time in the cool pantry. She sat on the floor and rubbed the apples to wipe off the dust and to bring out their shine. When they were as rosy as Isabella’s lips, she gathered them up and went back to the South Parlor, passing through the long-unused dining hall, where marks on the floor showed where the long table had once stood.

Isabella was sitting on her father’s lap on the big chair, her feet on the armrest. She squirmed, and her shoes made streaks on the cloth. Jane looked at Mamma, but Mamma appeared not to notice, and Jane put the food down and went to join Maude outside.

The sun was low, and the evening noises were starting. Crickets and tree frogs screeched out their songs, and a light breeze rustled through the trees beyond the henhouse, lifting a little of the heat from the late-summer day.

Maude showed Jane six new-laid eggs in her basket. “One for each of us and two for the man. He’s big and probably eats a lot,” Maude explained. She had placed them carefully in the basket, nestled in straw to keep them from breaking.

Jane picked the few remaining berries from a bush near the kitchen door. Walking carefully, she entered the South Parlor just as Maude was placing the egg basket on the scarred wooden table they used for everything from sewing to cooking to eating. Mamma had lit the lantern.

“Look what I have, Mamma,” Jane said. “We can eat these after the eggs.” She carefully pulled the berries out of her pockets, heaping them on the table.

“Lovely, dear,” Mamma said. “Where—”

But Isabella interrupted her. “I can’t eat those,” she said to her father. “She touched them with her dirty hands!”

“So wash them,” Jane said, as she would to Maude. Her fingers were a little grimy, she supposed, but none of it was nasty—just good, clean dirt from pushing branches aside and picking fallen berries up off the ground.