По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

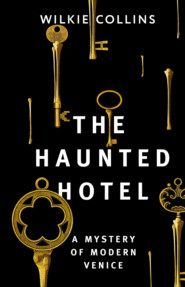

The Haunted Hotel / Отель с привидениями

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Chapter III

Doctor Wybrow lit his cigar, and looked round him at his brethren. The room was well filled. When he inquired if anybody knew the Countess Narona, everybody was astonished. What an absurd question! Every one knew the Countess Narona. An adventuress with a European reputation of the blackest possible colour – such was the general description of the woman with the deathlike complexion and the glittering eyes. It was doubtful whether she was really, what she called herself, a Dalmatian lady[8 - Dalmatian lady – уроженка Далмации (области на северо-западе Балканского полуострова)]. It was doubtful whether she had ever been married to the Count whose widow she assumed to be. It was doubtful whether the man who accompanied her in her travels (under the name of Baron Rivar, and in the character of her brother) was her brother at all. Report pointed to the Baron as a gambler at every ‘table’ on the Continent. And his so-called sister had escaped from a famous trial for poisoning in Vienna. Moreover, she had been known in Milan as a spy. Her apartment in Paris was nothing less than a private gambling-house.

Only one member of the assembly in the smoking-room took the part of this woman. But the man was a lawyer, and his interference was naturally attributed to the spirit of contradiction.

The Doctor inquired the name of the gentleman whom the Countess was going to marry.

His friends said that the Countess Narona had borrowed money in Homburg of Lord Montbarry, and had then deluded him into making her a proposal of marriage[9 - had then deluded him into making her a proposal of marriage – обманом вынудила потом предложение руки и сердца]. The younger members of the club sent a waiter for the ‘Peerage’[10 - the ‘Peerage’ – «Книга пэров»]; and read aloud about the nobleman.

‘Herbert John Westwick. First Baron Montbarry, of Montbarry, King’s County, Ireland. Created a Peer for distinguished military services in India. Born, 1812. Forty-eight years old, at the present time. Not married. Will be married next week. Heir presumptive, his lordship’s next brother, Stephen Robert, married to Ella, youngest daughter of the Reverend Silas Marden, Rector of Runnigate, and has three daughters. Younger brothers of his lordship, Francis and Henry, unmarried. Sisters of his lordship, Lady Barville, married to Sir Theodore Barville, Bart.; and Anne, widow of the late Peter Norbury, Esq., of Norbury Cross. Three brothers Westwick, Stephen, Francis, and Henry; and two sisters, Lady Barville and Mrs. Norbury. Not one of the five will be present at the marriage, Doctor; and not one of the five will leave a stone unturned to stop it, if the Countess will only give them a chance. Add to these hostile members of the family another offended relative not mentioned in the ‘Peerage,’ a young lady-’

A sudden outburst of protest stopped the disclosure.

‘Don’t mention the poor girl’s name. There is but one excuse for Montbarry – he is either a madman or a fool.’

The Doctor spoke confidentially to his neighbour and discovered that the lady was deserted by Lord Montbarry. Her name was Agnes Lockwood.

Soon a member of the club entered the smoking-room. His appearance instantly produced a dead silence. Doctor Wybrow’s neighbour whispered to him, ‘Montbarry’s brother – Henry Westwick!’

The new-comer looked said, with a bitter smile,

‘You are all talking of my brother. Don’t mind me[11 - Don’t mind me. – Не обращайте на меня внимания.]. I despise him. Go on, gentlemen – go on!’

But the lawyer undertook the defence of the Countess.

‘I stand alone in my opinion,’ he said, ‘and I am not ashamed of it. Why can’t the Countess Narona be Lord Montbarry’s wife? Who can say she has a mercenary motive?’

Montbarry’s brother turned sharply on the speaker.

‘I say it!’ he answered.

‘I believe I am right,’ the lawyer rejoined, ‘his lordship’s income is not more than sufficient to support his station in life. And it is an income derived almost entirely from landed property in Ireland, every acre of which is entailed[12 - every acre of which is entailed – каждый акр (той земли) – неотчуждаемая собственность].’

Montbarry’s brother had no objection.

‘If his lordship dies first,’ the lawyer proceeded, ‘if he leaves her a widow, four hundred pounds a year – is all that he can leave to the Countess. I know that.’

‘Four hundred a year is not all,’ was the reply to this. ‘My brother has insured his life for ten thousand pounds.’

This announcement produced a strong sensation. Men looked at each other, and repeated the words, ‘Ten thousand pounds!’

After that, the Doctor went home. But his curiosity about the Countess was not satisfied. He was wondering whether Lord Montbarry’s family would stop the marriage after all. And more than this, he wanted to see the man himself. Every day he visited the club to hear some news.

Nothing happened. The Countess’s position was secure; Montbarry’s resolution to be her husband was unshaken. They were both Roman Catholics, and they were to be married at the chapel in Spanish Place.

On the day of the wedding, the Doctor went out to see the marriage. The wedding was strictly private. A carriage stood at the church door; a few people, mostly of the lower class, and mostly old women, were near. Here and there Doctor Wybrow detected the faces of some of his brethren of the club. They were attracted by curiosity, like himself. Four persons only stood before the altar – the bride and bridegroom and their two witnesses. One of these last was an elderly woman; the other was undoubtedly her brother, Baron Rivar.

Lord Montbarry was a middle-aged military man. Nothing remarkable. Baron Rivar had moustache, bold eyes, and curling hair. And he was not in the least like his sister.

The priest was only a harmless, humble-looking old man.

From time to time the Doctor glanced round at the door or up at the galleries, anticipating the appearance of some protesting stranger. Nothing occurred – nothing extraordinary, nothing dramatic.

The married couple walked together down the nave to the door. Doctor Wybrow drew back as they approached. To his confusion and surprise, the Countess discovered him. He heard her say to her husband, ‘One moment; I see a friend.’ Lord Montbarry bowed and waited. She stepped up to the Doctor, took his hand, and wrung it hard.

‘One step more, you see, on the way to the end!’ She whispered those strange words, and returned to her husband.

Then Lord and Lady Montbarry stepped into their carriage, and drove away.

Outside the church door stood the three or four members of the club. They began with the Baron.

‘Damned ill-looking rascal!’

They went on with Montbarry.

‘Is he going to take that horrid woman with him to Ireland?’

‘No! They know about Agnes Lockwood.’

‘Well, but where is he going?’

‘To Scotland.’

‘Does she like that?’

‘It’s only for a fortnight. Then they will come back to London, and go abroad.’

‘And they will never return to England, eh?’

‘Who can tell? Did you see how she looked at Montbarry? Did you see her, Doctor?’

Doctor Wybrow remembered his patients, and walked off.

‘One step more, you see, on the way to the end,’ he repeated to himself, on his way home. What end?

Chapter IV

On the day of the marriage Agnes Lockwood sat alone in the little drawing-room of her London lodgings. She was burning the letters which Montbarry had written to her.

She looked by many years younger than she really was. With her fair complexion and her shy manner, she looked like a girl, although she was now really advancing towards thirty years of age. She lived alone with an old nurse, on a modest little income which was just enough to support the two. There were no signs of grief in her face, and she slowly tore the letters of her false lover in two, and threw the pieces into the small fire. She did not cry. Pale and quiet, with cold trembling fingers, she destroyed the letters one by one. She did not read them again.

The old nurse came in, and asked if she wanted to see ‘Master Henry,’ the youngest member of the Westwick family, who had publicly declared his contempt for his brother in the smoking-room of the club. Agnes hesitated.

A long time ago Henry Westwick said that he loved her. But she acknowledged that her heart was given to his eldest brother. He was disappointed; and they met thenceforth as cousins and friends. But now, on the very day of his brother’s marriage, she did not want to see him. The old nurse (who remembered them both in their cradles) observed her hesitation.

‘He says, he’s going away, my dear; and he only wants to shake hands, and say good-bye.’

Agnes decided to receive her cousin.

Doctor Wybrow lit his cigar, and looked round him at his brethren. The room was well filled. When he inquired if anybody knew the Countess Narona, everybody was astonished. What an absurd question! Every one knew the Countess Narona. An adventuress with a European reputation of the blackest possible colour – such was the general description of the woman with the deathlike complexion and the glittering eyes. It was doubtful whether she was really, what she called herself, a Dalmatian lady[8 - Dalmatian lady – уроженка Далмации (области на северо-западе Балканского полуострова)]. It was doubtful whether she had ever been married to the Count whose widow she assumed to be. It was doubtful whether the man who accompanied her in her travels (under the name of Baron Rivar, and in the character of her brother) was her brother at all. Report pointed to the Baron as a gambler at every ‘table’ on the Continent. And his so-called sister had escaped from a famous trial for poisoning in Vienna. Moreover, she had been known in Milan as a spy. Her apartment in Paris was nothing less than a private gambling-house.

Only one member of the assembly in the smoking-room took the part of this woman. But the man was a lawyer, and his interference was naturally attributed to the spirit of contradiction.

The Doctor inquired the name of the gentleman whom the Countess was going to marry.

His friends said that the Countess Narona had borrowed money in Homburg of Lord Montbarry, and had then deluded him into making her a proposal of marriage[9 - had then deluded him into making her a proposal of marriage – обманом вынудила потом предложение руки и сердца]. The younger members of the club sent a waiter for the ‘Peerage’[10 - the ‘Peerage’ – «Книга пэров»]; and read aloud about the nobleman.

‘Herbert John Westwick. First Baron Montbarry, of Montbarry, King’s County, Ireland. Created a Peer for distinguished military services in India. Born, 1812. Forty-eight years old, at the present time. Not married. Will be married next week. Heir presumptive, his lordship’s next brother, Stephen Robert, married to Ella, youngest daughter of the Reverend Silas Marden, Rector of Runnigate, and has three daughters. Younger brothers of his lordship, Francis and Henry, unmarried. Sisters of his lordship, Lady Barville, married to Sir Theodore Barville, Bart.; and Anne, widow of the late Peter Norbury, Esq., of Norbury Cross. Three brothers Westwick, Stephen, Francis, and Henry; and two sisters, Lady Barville and Mrs. Norbury. Not one of the five will be present at the marriage, Doctor; and not one of the five will leave a stone unturned to stop it, if the Countess will only give them a chance. Add to these hostile members of the family another offended relative not mentioned in the ‘Peerage,’ a young lady-’

A sudden outburst of protest stopped the disclosure.

‘Don’t mention the poor girl’s name. There is but one excuse for Montbarry – he is either a madman or a fool.’

The Doctor spoke confidentially to his neighbour and discovered that the lady was deserted by Lord Montbarry. Her name was Agnes Lockwood.

Soon a member of the club entered the smoking-room. His appearance instantly produced a dead silence. Doctor Wybrow’s neighbour whispered to him, ‘Montbarry’s brother – Henry Westwick!’

The new-comer looked said, with a bitter smile,

‘You are all talking of my brother. Don’t mind me[11 - Don’t mind me. – Не обращайте на меня внимания.]. I despise him. Go on, gentlemen – go on!’

But the lawyer undertook the defence of the Countess.

‘I stand alone in my opinion,’ he said, ‘and I am not ashamed of it. Why can’t the Countess Narona be Lord Montbarry’s wife? Who can say she has a mercenary motive?’

Montbarry’s brother turned sharply on the speaker.

‘I say it!’ he answered.

‘I believe I am right,’ the lawyer rejoined, ‘his lordship’s income is not more than sufficient to support his station in life. And it is an income derived almost entirely from landed property in Ireland, every acre of which is entailed[12 - every acre of which is entailed – каждый акр (той земли) – неотчуждаемая собственность].’

Montbarry’s brother had no objection.

‘If his lordship dies first,’ the lawyer proceeded, ‘if he leaves her a widow, four hundred pounds a year – is all that he can leave to the Countess. I know that.’

‘Four hundred a year is not all,’ was the reply to this. ‘My brother has insured his life for ten thousand pounds.’

This announcement produced a strong sensation. Men looked at each other, and repeated the words, ‘Ten thousand pounds!’

After that, the Doctor went home. But his curiosity about the Countess was not satisfied. He was wondering whether Lord Montbarry’s family would stop the marriage after all. And more than this, he wanted to see the man himself. Every day he visited the club to hear some news.

Nothing happened. The Countess’s position was secure; Montbarry’s resolution to be her husband was unshaken. They were both Roman Catholics, and they were to be married at the chapel in Spanish Place.

On the day of the wedding, the Doctor went out to see the marriage. The wedding was strictly private. A carriage stood at the church door; a few people, mostly of the lower class, and mostly old women, were near. Here and there Doctor Wybrow detected the faces of some of his brethren of the club. They were attracted by curiosity, like himself. Four persons only stood before the altar – the bride and bridegroom and their two witnesses. One of these last was an elderly woman; the other was undoubtedly her brother, Baron Rivar.

Lord Montbarry was a middle-aged military man. Nothing remarkable. Baron Rivar had moustache, bold eyes, and curling hair. And he was not in the least like his sister.

The priest was only a harmless, humble-looking old man.

From time to time the Doctor glanced round at the door or up at the galleries, anticipating the appearance of some protesting stranger. Nothing occurred – nothing extraordinary, nothing dramatic.

The married couple walked together down the nave to the door. Doctor Wybrow drew back as they approached. To his confusion and surprise, the Countess discovered him. He heard her say to her husband, ‘One moment; I see a friend.’ Lord Montbarry bowed and waited. She stepped up to the Doctor, took his hand, and wrung it hard.

‘One step more, you see, on the way to the end!’ She whispered those strange words, and returned to her husband.

Then Lord and Lady Montbarry stepped into their carriage, and drove away.

Outside the church door stood the three or four members of the club. They began with the Baron.

‘Damned ill-looking rascal!’

They went on with Montbarry.

‘Is he going to take that horrid woman with him to Ireland?’

‘No! They know about Agnes Lockwood.’

‘Well, but where is he going?’

‘To Scotland.’

‘Does she like that?’

‘It’s only for a fortnight. Then they will come back to London, and go abroad.’

‘And they will never return to England, eh?’

‘Who can tell? Did you see how she looked at Montbarry? Did you see her, Doctor?’

Doctor Wybrow remembered his patients, and walked off.

‘One step more, you see, on the way to the end,’ he repeated to himself, on his way home. What end?

Chapter IV

On the day of the marriage Agnes Lockwood sat alone in the little drawing-room of her London lodgings. She was burning the letters which Montbarry had written to her.

She looked by many years younger than she really was. With her fair complexion and her shy manner, she looked like a girl, although she was now really advancing towards thirty years of age. She lived alone with an old nurse, on a modest little income which was just enough to support the two. There were no signs of grief in her face, and she slowly tore the letters of her false lover in two, and threw the pieces into the small fire. She did not cry. Pale and quiet, with cold trembling fingers, she destroyed the letters one by one. She did not read them again.

The old nurse came in, and asked if she wanted to see ‘Master Henry,’ the youngest member of the Westwick family, who had publicly declared his contempt for his brother in the smoking-room of the club. Agnes hesitated.

A long time ago Henry Westwick said that he loved her. But she acknowledged that her heart was given to his eldest brother. He was disappointed; and they met thenceforth as cousins and friends. But now, on the very day of his brother’s marriage, she did not want to see him. The old nurse (who remembered them both in their cradles) observed her hesitation.

‘He says, he’s going away, my dear; and he only wants to shake hands, and say good-bye.’

Agnes decided to receive her cousin.