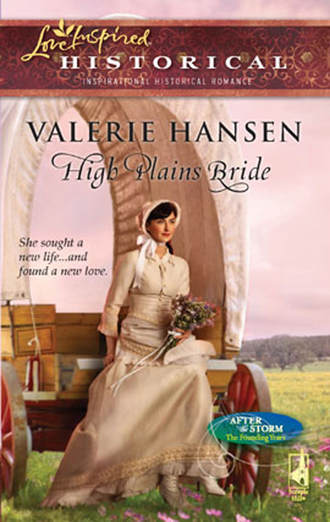

High Plains Bride

Those shelters would offer little protection against the upcoming storm. Will could only hope that the settlers would find refuge somewhere safe. The frequently occurring severe storms on the open plains could be dangerous—even deadly. And it looked as if they were in for another deluge within the next few hours.

Spurring his horse, he headed for his ranch at a brisk canter. There wasn’t a lot he could do for the longhorns he had grazing on the open prairie on both sides of the river, but it was sensible to send a few hands, including himself, to try to prevent a stampede among the critters closest to his house and barn. He just hoped a herd of nervous buffalo didn’t decide to run over his corn plot or trample his corrals the way one had during a bad lightning storm last summer. This storm was coming in fast, and would probably hit hard, pushing the livestock into a frenzy.

He pressed onward, hoping and praying that his instincts were wrong, yet positive that they were not.

The wind had increased and the sky had darkened menacingly by the time he reined in between the main ranch house and the barn. Several of his hands were already mounted and had bridled an extra horse, apparently awaiting his return, while the rangy ranch dogs barked excitedly and circled the riders.

“Clint, you and Bob take the south ridge,” Will shouted. “I’ll ride more west, then circle back to you.” He gestured as he dismounted. “This looks like a bad one.”

“Yeah, boss,” the lanky cowhand replied. “It ain’t gonna be pretty, that’s a fact. You want a fresh mount?”

“Yes.” Will threw a stirrup over his saddle horn and began to loosen his cinch. “Where’s Hank?”

“Already forded the river to try to round up the stragglers over there.”

“Good man.”

Clint nodded and passed the reins of the extra horse to Will, then spurred his mount and headed south with his partner as instructed.

Left alone, Will switched his saddle to the fresh horse, turned his tired sorrel into a corral and mounted up. He’d thought about taking the time to close the storm shutters on the house but had decided he shouldn’t delay getting to the herd. A building could be replaced fairly easily and besides, Hank was no longer inside where he could be hurt if it collapsed. Should this weather spawn a tornado, as Will feared it might, the old ranch cook would be much safer riding the range with him and the others, anyway.

Spurring the new horse, he raced toward open country. “Thank the good Lord I don’t have a wife and family to look after, too,” he muttered prayerfully.

His mind immediately jumped to the settlers in town, and the ones in the wagon train—to the pretty young woman in charge of so many children. Surely her father, or whoever was leading their party, would be wise enough to tarry in High Plains until the weather improved.

Emmeline was walking beside the family’s slowly moving, ox-pulled wagon while her mother lay inside on a narrow tick filled with straw and covered by a quilt.

Ruts in the trail made the wagon’s wooden wheels and axles bind and squeal as they bounced in and out of the depressions and jarred everyone and everything. Pots rattled. Chickens hanging in handmade crates along the outside of the wagon panted, squawked and jockeyed for space and footing on the slatted floors of their wooden boxes. The team plodded along, slow but sure, barely working to move the heavy wagon on the fairly level terrain.

Glory had quickly tired of walking. Emmeline had carried her on one hip for a while, then put her inside with their mother, in spite of the ailing woman’s protests that she simply could not cope with even one of her offspring.

Hoping that her father couldn’t hear her softly speaking, Emmeline gripped the top of the rear tailboard to steady herself and whispered hoarsely, “Hush.” She raised her head and gestured toward the man walking beside the oxen and prodding them with a staff when they faltered. “You know you’ll make Papa mad again if you raise a fuss.”

She hated having to be so cautious all the time, but the alternative was a beating for anyone within the wiry, older man’s reach, and she felt bound to try to protect the others. She’d had to do that more and more frequently, of late.

The sky was so dark at the horizon it seemed almost black, with a ribbon of pale sky showing beneath, as if a table sat atop a thin strip of the heavens visible only nearest the ground. Emmeline had seen weather like this back in Missouri, although not often. If she had been at home she would have gathered her siblings and shooed them into the root cellar for safety. Here on the plains she had no such option, much to her chagrin.

She hiked her skirts slightly to facilitate faster movement. A dozen swift steps brought her even with Amos and she easily kept pace. “Papa?”

“What do you want, girl?”

“Look at that sky. I’m worried.”

“I seen it. Don’t you go tellin’ me how to think, you hear? I been in storms worse’n this before and I’m still kickin’.”

“Yes, but—”

“Hush. Just because you’re nearly growed that don’t make you smarter’n me. I’ve been takin’ care of this family for longer than you’ve been on this earth and we’re all still here.” He glowered at her. “Well? You gonna waste the whole day naggin’ me or are you gonna go look after your mama?”

“Mama’s fine,” Emmeline insisted bravely, although she did put more distance between herself and the reach of her father’s heavy wooden staff. “She and Glory are taking a nap.”

Amos cursed under his breath. “Useless woman. I should’ve got me a younger wife long ago.”

It wasn’t the first time Emmeline had heard him say such mean-spirited things. She couldn’t imagine what her poor mama felt like when Papa talked like that. Little wonder Mama stayed in a sickbed so much. If and when she did arise, she had to face her husband and take more of his verbal—and physical—abuse.

Shading her eyes beneath the brim of her bonnet and squinting into the distance, Emmeline tensed. She hadn’t thought those clouds could possibly look any worse but they did. Rain was falling in the far distance, evidenced by slanted sheets of gray that streamed from the solid cloud layer toward the prairie in visible waves, indicating a downpour ahead.

She spun to scan the surrounding terrain. Darkness at midday was everywhere. Encroaching. Threatening. And the wind from the southwest was increasing, heralding the kind of destructive, unpredictable storm that she’d dreaded.

Emmeline shivered and pulled her shawl more tightly around her shoulders. If all they got from this weather was soaked to the skin and muddy, she’d count it a boon. In similar storms that she’d experienced back home, such signs of impending peril were not taken lightly.

She squinted. The kinds of menacing clouds she was looking at right now were capable of dealing a blow that could mean serious injury, loss of property—and perhaps even death.

Chapter Two

Now that Will was riding the high ground and could see for literally miles, his concern for High Plains increased. If he’d been a gambling man, which he was not, he’d have given even odds that his friends and their families would soon be in mortal danger.

Wind from the west and south was increasing, driving bits of stinging dirt and broken vegetation against his clothing and exposed hands and face. He crammed his hat on tighter, turned his back to the onslaught and fought to quiet his horse while he unrolled the slicker that had been tied behind the cantle of his saddle. The animal was clearly agitated, and well it should be under these circumstances, Will reasoned.

“Easy boy. Easy. We’ll be fine.”

As soon as he’d donned the slicker, he leaned low in the saddle and patted the horse’s lathered neck to try to reassure it, wishing he believed his own placating words.

Looking south, he saw that Clint and Bob had rounded up a large portion of his herd and were driving them in a tight circle to keep them controlled. Off to his right by about twenty degrees, an immense dust cloud was rising to meet the gray, somber heavens. The wind carried the sounds of shrill bleating and the rumbling drum of hundreds of cloven hooves.

So that’s what has my horse so riled up. Will put voice to his conclusion and patted the nervous animal again. “Buffalo. No wonder you’re so jumpy, boy. I am, too, now that I can tell what you smelled.”

Reining hard, he kicked the horse into a gallop and raced to join his men. This was just the beginning of what promised to be one of the wildest days he’d experienced since settling in the flint hills. He just hoped he and his men survived whatever test the weather had in store.

Amos had finally halted the Carters’ covered wagon, much to Emmeline’s relief. By that point, she had to shout at him to be heard over the howling wind. If she had not been wearing her bonnet she knew her cheeks would have already been blasted raw by the wind-driven prairie dirt and bits of broken vegetation that stung in spite of her clothing.

“What about the other wagons?” she screeched. “They stopped a half hour ago. Are we going to turn back and join them?”

“No need,” her father insisted. “We’ll just wait here a bit till the dust settles.”

She couldn’t believe his stubbornness. Not now. Not when they were in the middle of nowhere and basically alone. If it had been up to her she’d have at least tried to find a rock outcropping or gulley in which to shelter. Anything had to be better than just standing out in the open and taking so much punishment.

Hurrying to the rear of the wagon, she called to her sister Bess, who had taken up a position on the leeward side and was holding Missy’s and Mikey’s hands. “Take the twins off the trail and try to find some safe place to hunker down. I’ll bring Mama and Glory,” Emmeline shouted.

“What about Johnny?” Bess replied.

“Papa needs him to help calm the team.” Besides, she added to herself, instantly penitent, Johnny’s like Papa, too mean to get hurt.

She knew such thoughts had to be a sin, but she couldn’t help herself. If there was ever a mirror image of her father, it was her thirteen-year-old brother. Thank the Lord Bess and Glory were girls!

Emmeline watched as Bess tugged the fair-haired twins off the wide, rutted trail and into the thick stands of big and little bluestem. Surely there would be some hidey-hole out there. There had to be. Even the shallow depression of a buffalo wallow would be better than remaining in the wagon, which was already being rocked sideways by the strong winds.

She leaned her head and shoulders in over the tailboard and shouted, “Come with me, Mama. You and Glory will be safer outside.”

Joanna vehemently resisted as she clung to the five-year-old. “No. We’re staying right here. Your papa will take care of us.”

“Against this?”

Emmeline knew she was screeching at her poor mother, but she felt such tactics were necessary, given the dire circumstances. With the wind catching the fabric of her dress and petticoats and whipping them like an unfettered sail, she could barely stay on her feet. Soon, it would be impossible for any of them to successfully flee. If it wasn’t already too late.

“Yes,” Joanna said. “I’m not moving from this wagon and neither is my baby. If you want to run off and desert us, then go. I’m not holding you here.”

“Yes, you are,” Emmeline told her. “I won’t leave you.”

“And I won’t leave your father.”

“After the way he’s always treated you? How can you say that?”

“He’s my husband. I took holy vows and I intend to honor them,” Joanna said flatly. “Come in here with us, all of you.”

Glancing at the tall prairie grasses that were now slashing around like buggy whips and bending nearly flat to the ground Emmeline prayed that Bess and the twins had found suitable shelter. It was too late to go after them now. She’d have no chance of finding them in this turmoil.

She swiveled slowly, guarding her face by pressing the sides of her slat bonnet closer to her cheeks. Rain was beginning to fall in drops the size of apricot pits. That meant the whirling dust would no longer be so vexing, but that was little comfort, since hail was now starting to pelt her, too. It stung her skin like an assault of vicious hornets, striking her head, hands, arms and shoulders until she had to bite her lip to keep from crying out in pain.

That was enough to spur immediate action. Emmeline grabbed the tailgate of the wagon and leaped, hoisting herself over it and tumbling head-first into the straw-filled ticking beside her mother and youngest sister.

They reached out and embraced each other tightly, though their respite from nature’s onslaught was brief. Larger chunks of hail soon began to puncture the canvas roof, each impact making the rends in the fabric bigger, wider.

Wind then grabbed the loosening sheets, lifted and tore them, increasing the damage until there was little covering the wagon’s occupants except a few shreds of canvas, the bare bows and the bedding they clung to for what little protection it offered.

“Hang on!” Emmeline screamed, grabbing Glory more tightly and holding her close to shield the child with her own body.

Joanna was screeching, “Amos!” over and over again, to no avail.

Even if he had been close at hand, Emmeline knew he could not have heard anyone’s cries over the increasing roar of the storm.

It built until it was so deafening it made her ears ache and pop as if she were descending a mountain trail at a gallop. Suction from the spinning torrent pulled at her, foretelling what was about to happen.

“Twister!” Emmeline screamed at the top of her lungs.

She threw herself and Glory over their mother and clung to them both for dear life. Her calico skirt was tearing. Her bonnet was snatched from her head in spite of its tightly tied ribbons and her hair fanned out in a wild tangle, stinging her skin as it slapped her cheeks and neck.

Suddenly, she sensed herself being lifted until she felt weightless. She spun. Tumbled. Cracked the top of her head on one of the bows that arched over the wagon.

The rest of the world passed before her eyes in a fierce blur of colors accompanied by a painful, incessant battering and a dizzying disorientation beyond any she had ever experienced.

Still grasping Glory and trying to protect her small, fragile body with her own, Emmeline was carried away from their mother, from the battered wagon and its heavy-bodied ox team.

Praying wordlessly, thoughtlessly, she imagined that she’d glimpsed the team and wagon in the distance before she’d squeezed her eyes shut to try and stop her vertigo.

That sight had been so fleeting, so tenuous, she wasn’t positive it wasn’t imaginary. All she knew for certain was that they had been overtaken by an enormous twister and were totally at its mercy.

Please, God, let the others be all right.

That was the last lucid thought Emmeline had before blackness overcame her.

Will managed to reach his men and the milling cattle herd before the buffalo crested the nearest rise.

“You think you can handle ‘em?” he shouted to Clint.

“Yeah.” The other man pointed. “Can you turn that mess before it gets to us?”

“I’ll try.”

Hoping to divert the hundreds of stampeding wild buffalo, Will shouted and repeatedly fired his pistol in the air while spurring his reluctant horse to charge straight at them.

The lead bulls faltered little. On they ran, their sharp hooves churning the prairie and raising clouds of acrid dust that was caught by the fierce wind and driven against man and beast to sting like a myriad of tiny needles.

Fear pricked Will, too. He’d heard that bison were as easily redirected as cattle. He sure hoped that was true because unless they turned soon, there wouldn’t be enough left of him to find, let alone bury in the churchyard.

“Yah, yah,” he shouted, continuing to point his pistol in the air and fire. If he’d had his rifle loaded and ready he’d have tried to drop the leaders. Since he didn’t have that option at the moment he’d just have to persevere. And pray fervently that his method was successful.

About the time Will was getting ready to wheel his horse and try to make a dash to safety, the bulls running in front of the herd began to lead the others in a wide arc, avoiding the longhorn herd—and its owner—by a goodly margin.

Satisfied, Will reined in and raised in his stirrups to survey the distant plains while heavy rain continued to fall. He couldn’t see much to the west through the sheeting water, but it had to be plenty bad over that way. It didn’t look much better in the direction of his ranch house, either.

Well, that couldn’t be helped. The steers were the most important thing he owned. They were his livelihood. Everything else could fairly easily be replaced if it was damaged. He just hoped they hadn’t had too many newborn spring calves trampled beneath the hooves of the frightened, milling cattle or knocked unconscious by the hail, and that the men chasing down stragglers hadn’t been harmed.

Shading his eyes and peering into the distance, he tried to make out any signs of the wagon train that he’d encountered in High Plains. They’d still been encamped when he’d left town. Hopefully, they weren’t caught in the maelstrom he could see from the hilltop. If they were, God help them.

Relative calm soon followed the twister. Emmeline awoke to feel rain bathing her hair, her face and what was left of her favorite calico frock. She sat up slowly and wiped her muddy hands on her skirt before pushing her long hair back. It was not only loose and hopelessly tangled, it was matted with bits of straw, mud and goodness-knows-what-else that had come from the prairie.

The cool rain helped bring her to her senses and she raised her face to the heavens to wash her cheeks and help clear the irritating motes from her eyes.

Blinking, she drew a deep, shaky breath. Her ribs hurt a tad when she did so, but she didn’t think they were broken. At least not badly. And although her head was pounding and she had to continually try to clear her vision, the rest of her seemed to be in pretty fair shape, except for a few small cuts and scrapes. But what about the others?

Her heart leaped, her senses fully returning. “Glory!”

Quickly scanning her surroundings, Emmeline tried to spot her baby sister. Her hopes were dashed when she failed. She staggered to her feet, bracing against the milder wind that remained, and cupped her hands around her mouth. “Glory, answer me. Where are you?”

Soft weeping was the only reply.

Following that sound she soon found the little girl seated on the ground, grasping her bent knees and rocking back and forth.

Emmeline knelt and took the child in her arms. “Praise the Lord! Are you all right, Glory, honey?”

“I want Mama.”

Mama. Emmeline’s heart sped like the horrid wind that had decimated their party as her thoughts finally caught up to harsh reality. Where was Mama?

She was glad the rain falling on her face masked her tears because when she turned and spotted the remains of all their worldly possessions she couldn’t help weeping openly. Their heavy wagon lay on its top, wheels in the air like the feet of a long-dead prairie dog, and there was no sign of Papa and Johnny.

Where Mama had ended up was another question. If she was still in the inverted wagon, there was no possible way Emmeline could free her. Not without help.

And, thanks to Papa’s stubbornness, there was no way to tell how long it would be before anyone else knew what had befallen them. No way at all.

“Dear Jesus, help us. Help us all,” she prayed in a whisper as she lifted her little sister and started to carry her toward the wreckage.

Glory clung to her neck and sobbed. Emmeline was so concerned about their mother’s fate she was nearly back to the wagon before it occurred to her that Bess and the twins were unaccounted for, too!

Saying another quick prayer for her sister and the eight-year-olds, Emmeline approached the upset wagon cautiously. She was afraid of letting Glory see death for the first time in her short life.

As a small child, Emmeline had watched her maternal grandmother’s passing and had never gotten that image out of her mind, even though it had been a peaceful scene. Seeing their dear mother injured, or worse, would be terribly hard for a five-year-old to bear.

Emmeline called, “Mama,” and was rewarded by an answering call. It was muffled, due to the positioning of the upturned wagon, but strong nevertheless. Her tears became those of relief and joy.

“Mama? Are you stuck under there?”

“Yes. Go get your papa to help you get me out.”

“Okay. I’ll leave Glory here to talk to you.”

Joanna’s voice broke. “My baby’s all right? You both are? I thought…I was afraid…”

“We’re fine, Mama. Wet and muddy but otherwise fine.” She placed the little girl next to the wagon and told her to stay there, realizing that that command probably wouldn’t have been necessary. The child was already fully engrossed in chattering to their mother and wiggling her tiny fingers through narrow cracks in the wagon bed while she related their harrowing adventure. The scene was so touching it brought fresh tears to Emmeline’s eyes.

Cautiously circling the broken wreckage and trying to avoid the small patches of piled-up hail that the rain had not yet melted, Emmeline came upon one of their faithful oxen lying dead in its traces. Apparently, when the wagon had flipped over, the abrupt motion had snapped that poor animal’s neck and it had fallen where it stood.

The other side of the double yoke had broken, freeing the surviving ox, Big Jack. He stood apart from the carnage, trembling and staring at the death scene but apparently unhurt.

Johnny stood beside the lumbering animal, hugging its muscular neck and weeping like the child he still was.

Knowing there was nothing to be done for the dead animal, Emmeline went to her brother and gently touched his shoulder. “Are you okay?”

He nodded rapidly, hiding his face from his sister by pressing it to Big Jack’s slick, brown hide.

“Where’s Papa?” She held her breath and waited for his answer, never dreaming he’d turn and point back at the wagon tongue.

With that, the boy began to wail in earnest.

Emmeline spun around, her heart pounding, her breath catching in her throat. He couldn’t mean…Her eyes widened with shock. Clearly, he did.

She’d been so upset over the death of the faithful ox, she’d failed to look beneath and partially next to it. There lay the proof of disaster. Amos had stubbornly held out until the last and his folly had cost him dearly. The immense carcass of the animal had crashed down on his head and chest and snuffed out his life.

Even as she checked for signs of a heartbeat, she knew without a doubt that it was too late to do anything for him.

Fresh tears sprang to her eyes. Her father may have been a tyrant but he was still part of her family, part of her life, of Mama’s life. And now he was gone. Forever.

As she returned to her mother and youngest sister, Emmeline swiped at her damp cheeks. She was upset with herself for losing control and even more upset with her father for risking all their lives by pressing onward when he knew there was imminent danger.

And, she had to admit, she was also disappointed that her prayers for their safety had not been honored. Why not? Why had God taken Papa from them? Why hadn’t Bess and the twins returned to them? And why was Mama trapped?

Realizing that she still had much to be thankful for, Emmeline sobered and sighed. They’d lost one ox, one man and many of their belongings. But she and Mama and Glory and Johnny were still alive and kicking. And Bess and the twins would probably wander back to what was left of their wagon any moment now. Given the severity of the tornado and its accompanying storm, they had probably fared better than many others who had been caught up in the same terrible calamity.