По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

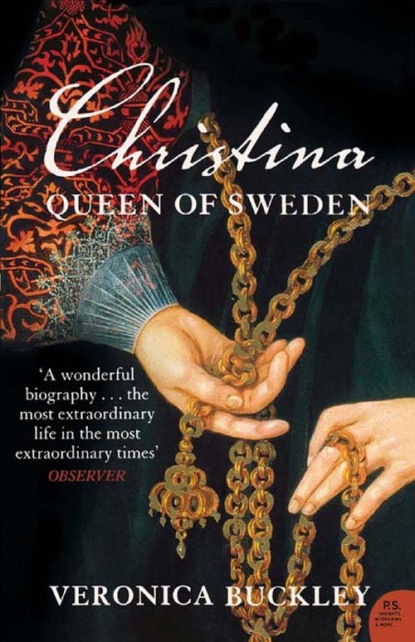

Christina Queen of Sweden: The Restless Life of a European Eccentric

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

This altercation, with its thinly veiled threats, does not seem to have made the slightest difference to Maria Eleonora. She had little to lose, in any case. The ‘warm affection’ in which her subjects supposedly held her was a myth, as both she and the Baron well knew. She was in fact exceedingly unpopular among the Swedes. From her earliest days as a young bride, she had made perfectly clear her disdain for her new home, frozen solid in winter, culturally primitive whatever the weather. Surrounding herself with exclusively German attendants, she had aroused the envy and resentment of the Swedish courtiers. Her new kinsmen, defensive and offended, had quickly reciprocated her dislike.

Now, however, she was at least cautious enough to lie to them. She wrote to Axel Oxenstierna declaring that she would not commit Christina to marrying anyone before she had reached the age of twelve and could give her own consent. She did not want her daughter to reproach her, she said, with having forced her into a marriage during her minority, adding disingenuously that she would welcome the Chancellor’s guidance in the matter. Once back in Stockholm, she informed the Elector’s envoy that she favoured the Brandenburg marriage after all. There was no one, she said, to whom she would rather give her daughter than her nephew Friedrich Wilhelm, but the problem was that ‘some people’ were against it. The Chancellor, she claimed, had plans to marry Christina to his own son, Erik, but, in a neat arabesque on her objection to Friedrich Wilhelm himself, she declared that she would never allow her daughter to marry a man of lower social position than she was herself.

By the beginning of 1634, six months after her regal reception of the Russian ambassadors, the betrothal of the now seven-year-old Christina to her Brandenburg cousin was understood throughout Europe to be a fait accompli. Resigned shoulders shrugged in Copenhagen, and an anxious Emperor paced the floors of his palace in Vienna. Only in Stockholm and Berlin did doubt remain, for the two protagonists had in fact reached no agreement at all.

Christina herself was never to mention her father’s plan for the Brandenburg marriage, for it clearly indicated that he had seen no particular ‘mark of greatness’ planted on her childish forehead. He had not intended her to rule alone, nor indeed perhaps even to rule at all. She chose to dwell instead on the instructions that he had left for her upbringing, exaggerating them to accommodate her own profound need to be accepted, not as the little Queen of Sweden, but as its divinely appointed King.

In the two years preceding the King’s death, Christina had seen equally little of her father and her mother. Whether following her husband on campaign or visiting her family in Brandenburg, Maria Eleonora appears to have given little thought to the child left behind. ‘My mother could not bear the sight of me,’ Christina was to write, ‘because I was a girl, and she said I was ugly.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Portraits of Christina in her early childhood depict nonetheless a charming little girl, though most are conventional, and all are no doubt flattering. It is true, however, that she was slightly deformed. As a baby, she had apparently been dropped, and her injuries had left her noticeably lopsided in the upper body, with one shoulder higher than the other; the portraits show her in tactful semi-profile. She herself was later to claim that this ‘dropping’ was no less than an attempt on her life commanded by Catholic sympathizers among her cousins, and at times even suggested that it had been her mother’s own idea. Whatever the truth, the resulting deformity cannot have endeared her to her beauty-loving mother. Had she wished to, however, Maria Eleonora might have seen herself reflected in the appearance of her only child; many extant portraits suggest that Christina owed not only her high forehead and her large, bright eyes to her mother as much as to her father, but also her distinctive, large nose. Like her mother, too, she was of delicate build. The difference between the two, it seemed, was not so much in feature as in nature.

For in those talents most evident in childhood, Christina was her father’s child. In her little person she carried a keen reminder of Gustav Adolf’s own physical hardiness, together with his able and enquiring mind. In both respects she seemed to those about her the very opposite of her frivolous, fluffily pretty mother, whose extravagant behaviour, untempered by any worthy achievement, had earned only disdain. The King had left a trace of his hot blood, too, pulsing in his daughter’s veins; her tendency to emotional outbursts, complete with tearfulness and violence, was a legacy of his own volatile temperament.

In the absence of both mother and father, Christina had spent most of her time with her family of Palatine cousins, who lived in unpretentious comfort at Stegeborg Castle, to the south of Stockholm. Her aunt was the Princess Katarina, the King’s elder half-sister, and her uncle Count Johann Kasimir of Pfalz-Zweibrücken, who had once accompanied Gustav Adolf to Berlin to meet the young Maria Eleonora. The Princess Katarina, aged then in her later forties, was the mother of five surviving children, the youngest still in his infancy; Christina describes her aunt as a woman of ‘consummate virtue and wisdom’. She had settled in easily with the other children; among this lively half dozen, she was fourth in age, with two little countesses, Maria Euphrosyne and Eleonora Katarina, a year or so either side of her. Her eldest cousin, some ten years older, was the Countess Kristina Magdalena, and there was a young boy, too, Karl Gustav, Christina’s senior by four years, and the baby, Adolf.

Her father’s untimely death had wrenched Christina from this comfortable environment and installed her against her will in her mother’s bizarre and gloomy apartments at Nyköping Castle; here she had been closeted for a year or more. ‘It would have been a lovely court if it hadn’t been spoiled by the Queen Mother’s mourning,’ Christina was to complain. ‘There is no country in the world where they mourn the dead as long as they do in Sweden. They take three or four years to bury them, and then when they do, all the relatives, especially the women, weep all over again as if the person had only just died.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Maria Eleonora ‘played the role of grieving widow marvellously well,’ she writes, insisting at the same time that her mother’s grief was sincere. ‘But I was even more desperate than she was, because of those long dreary ceremonies and all the sad and sorry people about me. I could hardly stand it. It was far worse for me than the King’s death itself. I had been quite consoled about that for a long time, because I didn’t realize what a misfortune it was. Children who expect to inherit a throne are easily consoled for the loss of their father.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Consoled or not, in the midst of her mother’s melodrama, Christina fell ill with the first of many maladies attributed by contemporaries, as by later scholars, to her distressed state of mind. She developed ‘a malignant abscess in my left breast, which brought on a fever with unbearable pain. At last it burst, releasing a great flow of matter. That did me good, and in a few days I was perfectly well again.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

After the King’s burial in June 1634, Maria Eleonora moved her court to the Tre Kronor Castle in Stockholm, near to the Riddarholm Church where her husband’s body was now entombed. Christina may have sensed a touch of theatricality in her mother’s extravagant mourning, but to the four regents who remained in Sweden, it seemed real enough. Taking advantage of the move to Stockholm, they proposed to place the child in separate apartments within the castle, but the suggestion drew forth ‘pitiful tears and cries’ from her mother. Axel Oxenstierna, writing from Germany where he had remained to continue direction of Sweden’s armies, urged the senators to insist: the child must be taken from her mother; the late King himself had warned that Maria Eleonora was not to be permitted any influence over her. The senators, it seems, were divided; some felt that the child should be left where she was; others wanted to send the Queen Mother back to Nyköping by herself. Every remonstrance with Maria Eleonora was met with fresh hysterics, so that the senators, torn between sympathy and exasperation, came to no conclusion at all; their wavering condemned the little Queen to two further miserably cloistered years. Affording her daughter no respite, Maria Eleonora did claim some at least for herself. With surprising initiative, but little persistence, she made plan after plan for elaborate memorials to her late husband. There was to be a new tomb, then a new chapel, then a new castle, then a whole new city. One French envoy, flattered to be consulted by ‘this charming woman’, recorded his delight in discussing with her ‘the finer points of every branch of architecture, of Doric and Ionic and Corinthian columns’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Needless to say, no stone was ever laid.

Christina, meanwhile, did what she could herself to escape. The means at her disposal were slender, but she exploited them, or so she claims, to the full. Her hours of exercise and especially of schooling became her refuge. The mother’s weakness was turned to the daughter’s profit. ‘What I endured with her,’ she writes, ‘made me turn all the more keenly to my books, and that is why I made such surprisingly good progress – I used them as a pretext to escape the Queen my mother.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The indecisive senators had at least been able to agree on the kind of education the child should receive; in fact, prompted by their absent Chancellor, the entire Riksdag had discussed it, and in March 1635, with Christina already eight years old, they made their conclusions known. Their priorities are revealing. The little Queen must learn, states their preamble, ‘to speak well of her subjects and of the present state of the country and of the regency’. Though she must learn something of foreign manners and customs ‘as becomes her station’, she must also ‘practise and observe Swedish ones and be taught them carefully’. She must learn table manners, too, they declared, without, however, specifying whether these were to be homegrown or of some foreign variety.

The men of the Riksdag were clearly anxious that Maria Eleonora’s widely known disdain for all things Swedish should not be inculcated in her daughter. Other foreign errors were also to be strenuously avoided, notably those of popery and Calvinism. The ‘art of government’ was acknowledged to be important for her to learn, but ‘as this sort of knowledge is learnt rather with age and experience than by the studies of childhood, and as the knowledge of God and his worship is the true foundation of all else, it is most salutary that she should first and foremost study the word of God, the articles of faith and all the Christian virtues’.

(#litres_trial_promo) She must also learn ‘to write well and to calculate quickly’, and she must read only those books which had been approved by learned men of suitably moral temper. The programme for her education was to be reviewed as the little Queen progressed.

Gustav Adolf had also been concerned to prevent Maria Eleonora from influencing their daughter adversely. From his campaigns abroad, he had sent back detailed instructions about her upbringing in the event of his own death. The Queen was to be excluded from any regency, and three named men were to be appointed to oversee the child’s education. Her two governors were to be Axel Banér and Gustav Horn, both senators. As tutor she was to have Johan Matthiae, a theologian and former schoolmaster, and the late King’s own chaplain. The two governors were both expert in the use of arms, and both were hard drinkers, but otherwise they were very different men, Banér apparently something of a rough diamond with a penchant for pretty women, Horn more of a courtier, fluent in foreign languages and an experienced diplomat. The tutor, Johan Matthiae, well born and well educated, had studied not only in Sweden’s own university at Uppsala, but also in the German lands as well as in Holland, France, and England. He was a man of calm and kindly temperament, liberal in his thinking, especially in religious matters; in this he reflected, as he had no doubt helped to form, the views of his late King.

Unlike the ‘five great old men’ who comprised her regency, Christina’s governors and tutor were young, all in their thirties at the time of their appointment, Gustav Horn indeed barely so. Two at least had been Gustav Adolf’s beloved friends, Banér even sharing the King’s bedchamber before his marriage and afterwards, whenever the Queen was absent. Johan Matthiae, too, had accompanied the King on campaign. Christina later described them all as ‘capable, good men’. She appreciated the straightforward honesty of Banér, and admired Horn’s foreign polish, but for her tutor she reserved a special fondness. She called him ‘Papa’, and he quickly became the confidant of all her little secrets, a steady and reassuring presence in her difficult young life.

The late King’s choice of guardians, according to their little charge herself, writing many years later, was ‘as happy as it could be, given that none of them were Catholic’. Together, they formed a vital counterweight to the extremities of Maria Eleonora’s court, and provided an outlet for the frustrated energies of a bright and active child. But the Queen Mother’s continuing obsessive behaviour during these years destroyed any chance for a real affection to develop between herself and her daughter. Though Christina claims to have loved her mother ‘tenderly enough’, her respect for her began to fade, she says, when she ‘seized me, in spite of my tutors, and tried to lock me up with her in her apartment’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Three years were to pass before her eventual release, in the summer of 1636, on the return of Axel Oxenstierna to Sweden. More determined and less manipulable than his brother senators, the Chancellor removed Christina at once from her mother’s suffocating embrace, and placed her again in the care of the Princess Katarina, with whose two younger daughters she now continued her schooling. The Queen Mother herself was also promptly removed, and placed under comfortable but tedious guard in the island castle of Gripsholm at Mariefred, some fifty miles from Stockholm. Like her own once imprisoned daughter, Maria Eleonora would do her best to escape.

Love and Learning (#ulink_449fa6d6-957f-5e61-8c2b-0dcf171cae9d)

Christina was once more in the safe and steady care of her Aunt Katarina. With her tenth birthday approaching, she was now taking her lessons in the company of her two cousins, Maria Euphrosyne, aged eleven, and Eleonora Katarina, aged nine. The three girls seem to have shared an easy friendship, though Christina did complain – to their father – that her elder cousin was falling behind in her schoolwork; it would be a good idea, she suggested, if he made her work a bit harder.

The late King had left instructions that his daughter was to receive ‘the education of a prince’, and to take plenty of exercise, an uncommon emphasis for a girl of the time. He had no doubt seen that, even as a little child, she was physically very active, and perhaps, too, he had wished to distance her from the precious femininity which her mother had evinced. Christina was to be trained to only two conventionally feminine habits: modesty and virtue, though in the former, at least, she was to fail spectacularly. But her schooling with the two little countesses suggests that her academic training was not exceptional for a girl of her position. Though she may have been more capable than either of her cousins, they all read the same texts and wrote the same inkblotted exercises.

In later years, Christina’s accomplishments were to be the subject of a good deal of extravagant praise, not least from her own pen. It is certain that she was a clever and inquisitive child who enjoyed learning. She welcomed this ‘pretext to escape the Queen my mother’, and claimed that by the age of eight she was already studying twelve hours every day ‘with an inconceivable joy’, though she does not say that by the same age she was given to wild exaggeration. Seen against the background of prevailing standards, her schooling was very good indeed, for until the most recent years, education in Sweden had been deplorable. Only a few years before Christina’s birth, with the country at war with Poland, there was not a single diplomat available with enough Latin to conduct negotiations with the enemy. Many local officials, it seems, ‘could not even write their names’.

(#litres_trial_promo) Older men had gone abroad for their education, if indeed they had received any, generally to Leiden, or to one of the German universities. Only the clergy had been schooled at home. A young man might study theology or biblical languages in Sweden, but none of the ‘modern’ subjects of law, history, politics, mathematics, or science; all these Gustav Adolf had introduced as part of his great internal reforms of the 1620s. He had established grammar schools, too, and revived Sweden’s only university, at Uppsala, with endowments of land and with books and scientific instruments, the booty of his German campaigns. But progress had been slow: in 1627 the university had been able to boast just four history students, with five newcomers for law, and two for medicine. Even by 1632, at a vital period of the war in Germany, there had been no one capable of serving as secretary to any of Sweden’s generals in the field – only theologians were available. And Christina was ten years old before the first lektor in modern languages was appointed; German being regarded as almost a native tongue, the new appointee taught French.

In the light of this situation, it is not surprising that Christina’s contemporaries were impressed by her educational accomplishments. The regents, apprehensive of her mother’s legacy, were relieved to find her a clever and studious child. As she grew to womanhood, foreign diplomats and other visitors were quick to praise, though the scholars who later came to Stockholm were generally disappointed, finding her brilliant reputation undeserved. But if her fame eventually promised more than she merited, it was not for want of good schooling. The late King had prescribed for his daughter a broad humanist education, progressive in some details, but on the whole a legacy of the great Renaissance tradition in which he himself had been brought up. Gustav Adolf’s tutors had been independently minded men, and this in turn did much to shape the education that Christina herself now received. Like her father, she was inquisitive, strong-willed, and eager to learn, but unlike him, she had no particular enthusiasm for the ‘Christian virtues’ which were expected to be the basis of all her learning. By her own admission, the only parts of the scriptures she cared for were the Book of Wisdom and ‘the works of Solomon’ – in short, the most secular parts. She remained unmoved by the Gospels, and her lack of devotion to – indeed, lack of any interest in – the person of Jesus Christ was to remain a curious blank in her dramatic religious development. Nevertheless, for a few years during her girlhood, she was intensely pious, even to the point of bigotry. It was hardly surprising, given the narrow brand of Lutheranism prevailing in Sweden at the time, but it also reflected Christina’s own very determined nature. A touch of self-righteousness, untempered by experience, led very naturally to dogmatism. Not least, for a girl who enjoyed confrontation, a staunch Lutheran conviction was in direct opposition to her tutor’s own evenhanded views; Johan Matthiae’s firm belief was in a future union of all Protestant creeds.

Christina’s piety, whatever its cause, did not help her to endure the many long and dreary sermons of the Swedish Church. She hated them, she said, with ‘a deadly hatred’, though one of them did inspire her, at least temporarily, with a solid Lutheran fear of the Lord. Its subject was the Last Judgement, and it was preached every year just before Advent, and hence just before her birthday. It was a reliably ferocious tirade, full of hellfire and brimstone, and, to a sensitive and imaginative child, really terrifying. Hearing it for the first time, Christina turned in frightened tears to Johan Matthiae, who comforted her with the promise that she would escape damnation and live forever in Heaven – provided she was ‘a good girl’ and applied herself properly to her lessons. Christina took the warning seriously, and did her best to behave, but the following year, on hearing the same sermon, she found it somehow less menacing. Another year later, the menace had retreated further still, so far, in fact, that she ventured to suggest to Matthiae that it was all a lot of nonsense, and not just the threats of damnation, but all the rest of the stories, too – the Resurrection of Jesus, and everything. Matthiae was alarmed, and warned her in serious tones that thinking of that kind would certainly lead her down the road to perdition. Christina respected her ‘Papa’, and loved him, too, and she said no more on the subject. But the seed of doubt had fallen on fertile ground. By the time she was out of her girlhood, Christina believed ‘nothing at all of the religion in which I was brought up’, and she later declared that all of Christianity was ‘no more than a trick played by the powerful to keep the humble people down’.

Matthiae was a theologian and a Lutheran clergyman, but his views were liberal. He admired the great humanist tradition, and made it part of Christina’s daily lessons along with the harangues of Roman senators and the dry texts of the Swedish constitution. Christina was particularly attracted to neostoicism, a revival of ancient Stoic thought in a form compatible with Christianity – the inconvenient materialist beliefs of the Romans, for example, had been modified away. In neostoicism, she found a bridge between the Lutheran world that she was gradually abandoning and the classical deism that she was moving towards. The humanists had not gone so far, but Christina read into them what she needed to see, and for now, and for years to come, a deity unhampered by sect or priest or bible was precisely what she wanted to believe in. Besides, the earnest bravery of the neostoics was a perfect complement to the heroic classical tales that she so loved, and it encouraged her enthusiasm for the bookish, boyish virtues – mens sana in corpore sano – of the disciplined Roman Republic. In her fifteenth year, Matthiae introduced her to Lipsius’ Politica, a collection of pithy classical maxims well suited to her own rather apodictical nature. She was never to lose her taste for maxims; from those of ancient Greece and Rome she progressed to those of modern France, and in later life she wrote some of her own, happily contradicting herself with the courage of each changing conviction.

Christina’s religious studies were conducted in German and Swedish, and also in Latin, which she had begun to study seriously. Matthiae had compiled for her a brief summary of Latin grammar, using as his guide Comenius’ recently published Janua linguarum reserata – The Door to Languages Opened.

(#litres_trial_promo) Comenius held the then revolutionary idea that lessons should be adapted to the age and ability of the pupil; he was later to produce the first teaching book which combined text with pictures.

(#litres_trial_promo) His innovative Latin grammar was built not around abstract rules but around the familiar objects of childhood, but despite this, Christina declared that she hated it so much she almost stopped learning Latin altogether. This she would not have been permitted to do; Latin was essential, a written and spoken lingua franca used everywhere in Christendom. Her father had learned to speak it perfectly before he could read in any language, and Christina claimed the same facility for herself, though this was probably untrue; her progress in Latin was unremarkable, and as a young girl, at least, she was reluctant to speak it. Matthiae wanted her to speak to him only in Latin, but she would not; a brief memorandum on the subject, written shortly before her tenth birthday, reveals the state of the case. In schoolgirl Latin, and using the royal ‘We’, she wrote: ‘We hereby promise to speak Latin with Our tutor from now on. We will hold Ourselves to this obligation. We know We have promised this before, and not kept Our word. But with God’s help, We will keep it this time, beginning next Monday, God willing. Written and signed by Our own hand…’

(#litres_trial_promo)

Whether or not she kept her promise ‘this time’ is not known, though she spoke the language well enough in later life. But if she did not like learning Latin, she did enjoy the history accessible through it, and in this she was spurred on by the Royal Librarian, Johann Freinsheim, an authority on Tacitus who taught her most of her Roman history. He seems to have taught her well, for in later years, the French ambassador noted that she seemed to have no trouble with Tacitus, ‘even the difficult passages, which I found hard myself’. But it was not the quality of Tacitus’ writing that attracted Christina. She loved the stories of the ancient world, loved reading of the heroic exploits of Caesar and Alexander, loved the tales of nobility and virtue and the unending quest for glory. They were for her a world of adventure, where bravery and fortitude triumphed, a world of danger and daring where the strong took all and the wisest man was the unflinching stoic. To her they outshone even her own great father, and in her extravagant expectations of what she herself would accomplish, she identified herself with them. Not content with reading about them, she took to writing about them, too: a brief ten pages on Caesar, and a more substantial essay on Alexander, which ran to seven drafts – very little changed from one to the next, however, and all but the first copied out in the weary hand of a court scribe. Alexander remained her greatest hero, and she lived surrounded by his exploits: even the walls of her own room in the castle were hung with tapestries depicting them. Matthiae taught her no Greek, but Christina later persuaded Freinsheim to help her study it, and found a new hero in the Persian Emperor Cyrus, brought to life in Xenophon’s Cyropaedia, a popular mélange of fact and fiction then widely read by schoolboys. Christina admired the faultless Cyrus, but did not seek to emulate him. Caesar and Alexander, though rougher diamonds, produced, she thought, a greater light.

Matthiae records that by the time she was eleven, they had read together ‘the usual beginner’s Latin texts’,

(#litres_trial_promo) including some of Curtius’ History of Alexander the Great, which the young Diana loved especially. Christina believed that she ‘surpassed the capacity of my age and sex’, but she was very quick to exaggerate her achievements. She wrote, for example, that by the age of fourteen she had learned, ‘with a marvellous facility’, all the sciences, languages, and other studies in which she had been instructed. In the very next breath, she claimed that for modern languages, at least, she had received no instruction at all, any more than she had done for her mother tongue of Swedish. ‘I never had a teacher,’ she writes, ‘for German, French, Italian, or Spanish.’

(#litres_trial_promo) In fact, she had spoken German from her infancy; she had used it with her mother and her father, and it seems to have been the first language she learned to write. In French, she had regular lessons for some years. Matthiae records that he began teaching her French grammar when she was twelve years old, but she had learned to speak the language long before then. Living with her Palatine cousins had provided the occasion; they were the first family in Sweden where French was spoken at home – a decided affectation in the eyes of the other nobles, but it gave Christina an easy familiarity with the language, though, even in an age of unsettled orthography, her spelling was quite unusual. French remained her preferred language, and in later years she used it almost always, even when writing to friends and family in Sweden.

The modern languages, in any case, were not of great interest to her during her girlhood. Her heart was in the ancient world, where all her heroes had fought their battles in field and forum. The classical texts served many purposes; they included literature and philosophy and the history that she loved, but they were also an important part of the young Queen’s political education, tried and tested examples of realpolitik from which a present-day ruler might take counsel. Christina enjoyed this aspect of her training in the ‘art of government’. She likened the ancient political feuds to games of chess in which the shrewdest manipulator took the prize, and liked to think of herself as a master of ‘dissembling’ – it was one of her favourite words – who could always outwit even the cleverest men about her, including Chancellor Oxenstierna himself. He was now spending several hours each day instructing her in practical politics and statecraft. These hours she relished: the Chancellor was a man of vast experience, who knew ‘the strengths and weaknesses of every state in Europe’, and she listened, enchanted, to his first-hand stories of battles planned and bargains struck and enemies undermined. ‘I really loved hearing him speak,’ she writes, ‘and there was no study or game or pleasure that I wouldn’t leave willingly to listen to him. By the same token, he really loved teaching me, and we would spend three or four hours or even longer together, perfectly happy with each other. And if I may say so, without undue pride, the great man was more than once forced to admire the child, so talented, so eager and so quick to learn, without fully understanding what it was that he admired – it was so rare in one so young.’

(#litres_trial_promo)

It is not very likely that the Chancellor’s understanding failed him now as he contemplated the talents of his young pupil. Axel Oxenstierna was among the most gifted men of his generation, and he had comfortably taken the measure of the likes of Cardinal Richelieu while keeping the upper hand, 500 miles distant, of his every opponent at home. But he was certainly pleased with Christina’s progress, reporting to the Senate with satisfaction that the young Queen was ‘not like other members of her sex. She is stout-hearted and of good understanding,’ he said, ‘to such an extent that, if she does not allow herself to be corrupted, she raises the highest hopes.’

(#litres_trial_promo) The Chancellor did not elucidate the nature of Christina’s possible corruption, but his reference to her ‘allowing herself’ to be corrupted suggests that he had observed some weakness or unwelcome tendency in her nature. It was no outward menace that he feared for her, but rather, it seems, the consequences of her own contradictory self. He may have been made anxious, perhaps even saddened, by the small deceits which she had begun to practise on him through her correspondence with her Palatine uncle, Johann Kasimir. The Count had once served her father as Grand Treasurer, but shortly after the King’s death, he had been given a clear hint to resign from his position and betake himself to the country. The regents and senators disliked his German origins and suspected him of harbouring too great ambitions for his elder son, Karl Gustav. Christina’s ‘wise and prudent’ uncle swallowed the insult and retired without demur, but he kept in touch with her, and she seems to have enjoyed the opportunities for petty subterfuge which his ambiguous position provided.

As part of her training in statecraft, Christina had studied Camden’s Latin biography of Elizabeth I of England, the Virgin Queen with the ‘heart and stomach of a King’ who had overseen the defeat of the Spanish Armada fifty years before.

(#litres_trial_promo) The Protestant Queen Elizabeth was widely known and admired in Sweden, and during Christina’s girlhood, memories of her were still fresh in many minds. King Erik XIV, Christina’s own great-uncle, had for many years been her suitor, and Christina’s great-aunt Cecilia had made a ‘pilgrimage of admiration’ to her court. Elizabeth’s history was heroic; like Christina, she had inherited an uncertain crown; she had bravely endured five years of imprisonment with the axeman waiting at the door, and in the cold and fearful meantime she had perfected her many accomplishments. ‘Shee was even a miracle for her learning amongst the Princes of her time,’ Camden wrote of Elizabeth. ‘Before she was seventeene yeeres of age, she understood well the Latin, French and Italian tongues.’ She had studied Greek as well, which Christina had not yet done, and she was a good musician, too. Elizabeth’s wide culture, her strength of mind, and, not least, her mastery of statecraft, had framed a golden age for her small country, which, like Christina’s Sweden, had only recently emerged on to the world’s wide stage. It was agreed that a queen like Elizabeth would be a fine successor to the great Gustav Adolf, and her glorious reign seems to have aroused Christina’s envy. In a later rant against all women rulers, she avoided mentioning the legendary English Queen, but Elizabeth’s shadow lingers nonetheless in a series of phrases anticipating the obvious interjection of her name: there have been no good women rulers, or if there have, none ‘in our present century’; women are weak ‘in soul and body and mind’, and if there have been a few strong women, well, that’s not because they were women. For Christina, the capable woman ruler was merely the exception that proved the rule. She took her model of all women from her mother, and declared that, of all human defects, to be a woman was the worst:

As a young girl I had an overwhelming aversion to everything that women do and say. I couldn’t bear their tight-fitting, fussy clothes. I took no care of my complexion or my figure or the rest of my appearance. I never wore a hat or a mask, and scarcely ever wore gloves. I despised everything belonging to my sex, hardly excluding modesty and propriety. I couldn’t stand long dresses and I only wanted to wear short skirts. What’s more, I was so hopeless at all the womanly crafts that no one could ever teach me anything about them.

(#litres_trial_promo)

Christina’s ungenerous attitude towards her own sex had been long fomenting. The hyperfemininity of her unloving mother cannot have helped, but her distaste for all things feminine was mostly, it seems, the result of her own very masculine nature. The late King’s instructions that she should have a ‘princely’ education consequently accorded very well with what she herself most enjoyed. Even her dolls, it seems, were the classic toys of little boys. They were ‘pieces of lead which I used to learn military manoeuvres. They formed a little army that I set out on my table in battle formation. I had little ships all decked out for war, little forts, and maps.’

(#litres_trial_promo) Whether they were really her own toys, or whether they were inherited from her cousins, Karl Gustav and Adolf, Christina does not say, but her enthusiasm for them was genuine enough; she loved cannon and swords and all things military. She loved being outdoors, too, and loved animals, especially horses and dogs; when Karl Gustav went off to university, he left his gun-dogs in her particular care. She believed that every animal possessed its own individual soul, and was prepared to contradict the opinion of the great Descartes on the subject. For Descartes, a quintessentially indoor philosopher, animals were no more than living machines, but Christina’s experience of the different temperaments of her own horses and dogs convinced her otherwise.

‘I can handle any sort of arms passably well,’ she wrote, ‘though I was barely taught to use them at all.’ From this it seems that she must have learned to fence, but if she did not receive much instruction, this is not surprising. Fencing was an aspect of military training, and consequently not something that any girl, even an honorary prince, would be expected to need. Perhaps Christina persuaded one of her governors, both expert swordsmen, to give her a few lessons, or perhaps her two cousins, happy to display their boyhood skills, passed on to her some of their own instruction. Christina did not keep up her fencing, though from time to time in her adult life she liked to wear a sword.