По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

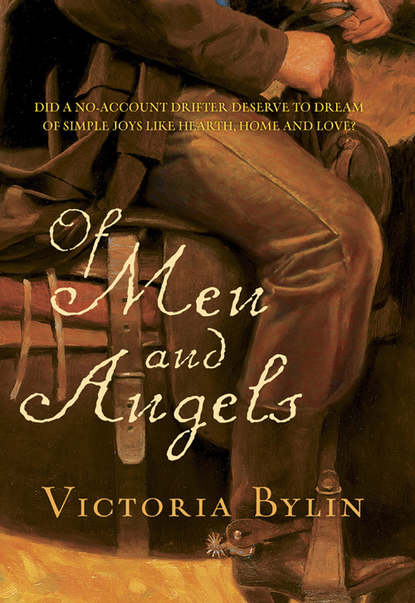

Of Men And Angels

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

“If you tend to the baby, I’ll see to the mother,” he said.

“Who are you?” Her voice was hoarse, and he could see every minute of the past twenty-four hours in her face. Something stirred in his gut, and an un-characteristic urge to be kind softened his eyes.

“My friends call me Jake.”

“I thought you were…” She shook her head. “I thought I imagined you.”

She looked as if she could still hear Charlotte’s moans, and he wondered if she would ever sing that hymn again. He looked at her eyes, red rimmed and inflamed with the dust and the sun, and somehow he knew she would sing it again this very day, just to make a point.

Brushing off her hands, she rose and smoothed her skirt. Jake tethered the bay to the stagecoach and inspected the mule writhing in the harness. If the animal could walk, perhaps the woman and baby could ride it.

“Whoa, boy,” he said, but the beast didn’t want anything to do with him. A broken foreleg told Jake all he had to know. He pulled his Colt .45 from its holster, cocked the hammer and put the animal out of its misery.

The angel gasped at the sudden blast. He expected her to be hysterical or sentimental about the animal, but she didn’t say a word and he had to admire her. She had been a fool to travel the Colorado Plateau alone, but she wasn’t softhearted about life.

Jake holstered the Colt and opened the driver’s boot. The mail was ruined, but the tools were in place and he took out the shovel. He wondered about the driver and man on shotgun, but the watermarks in the gorge made the facts plain. The two men had drowned in the flood.

Jabbing the shovel into the ground, Jake took a pair of leather gloves from his saddlebag and looked for a suitable grave site. He wasn’t about to bury Charlotte where a flash flood could steal the body, so with his black duster billowing behind him, he climbed over the cascade of rocks on the far side of the gorge.

The iron-rich plains stretched for a million miles, but just a few feet away he saw a sprig of desert paintbrush. It was the best he could do, and he started to dig. When the hole was deep, he collected rocks from the streambed and piled them nearby.

Two hours had passed when he wiped his hands on his pants and looked at the sky. The sun was lower now, as bright as orange fire, and above it, flat-bottomed clouds boiled into steamy gray peaks. Another storm was coming, he could smell it in the air.

He jabbed the shovel into the earth and strode down the rocky slope. The angel was holding the baby, crooning to it in that sweet voice of hers. It was bundled in something clean and white, and she had managed to dress the mother in a fashionable traveling suit.

Without a word, he brushed by the angel and scooped Charlotte into his arms, rocked back on his heels and rose to his full height.

He felt the angel’s gaze as he walked past her, and rocks skittered as she followed him. As gently as he could, he laid the dead woman to rest, picked up the shovel and replaced the dirt. He half expected the woman named Alex to pray or say a few words, but she settled for a mournful humming that made him think of birds in autumn and the wail of the wind.

Down in the valley, the valley so low,

Hang your head over, hear the wind blow.

One by one he piled jagged rocks on the loose earth. Alex didn’t flinch. The child mewled now and then, but her humming soothed him. It should have soothed Jake, too, but it didn’t. His head had started to pound, his back hurt, and his stomach was raw with bad whiskey.

A few hours ago he had been on his way to California, or maybe south to Mexico. He was alone by choice, and now he was stuck with a woman and a child. His life had taken a strange turn indeed.

He set the last rock on the grave with a thud and took off his gloves. Studying the angel’s profile, he said, “I’m done.”

She turned to him, and in her eyes he saw the haunted look of a person seeing time stop.

“I suppose you should say a few words,” she said.

His mouth twisted into a sneer, and he stared at her until she understood he had nothing to say. Bowing her head, she uttered a prayer that told him Charlotte was a stranger to her, this child an orphan, and the angel herself a woman who had more faith than common sense.

A determined amen came from her lips. The baby squirmed and, cocking her head as if the world had tilted on its axis, she looked at his face.

“You’re hurt,” she said.

He shrugged. Bruises were common in his life, like hangnails and stubbed toes. Bending down on one knee, he straightened a rock on the grave. “She had a bad time.”

The angel’s skirt swished near his face. He stood up and she sighed. “I’ve never seen someone die before.”

“I have.”

She gaped at him, and he felt like Clay Allison and Jesse James rolled into one. The corners of his mouth curled upward. He wasn’t in the same class as the James Brothers, but with his black duster, two black eyes and a three-day beard, any sensible woman would have crossed the street at the sight of him. He could have scared her even more with the truth. He’d shot a man, and depending on Henry Abbott’s stubbornness, Jake was either a free man or wanted for murder.

“Death isn’t a pretty sight,” he finally said.

She went pale. “My father is ill. I have to get to Grand Junction. Could you take us there?”

If he didn’t take her, the baby would die. Was there even a choice here?

There’s always a choice, Jake, and you’re making the wrong one. Lettie Abbott’s angry face rose up from the hot earth, shimmering with accusations, and he didn’t answer.

The angel was close to begging. “I have to get home as soon as I can. I know it’s out of your way, but I could pay you.”

He considered taking her up on the offer, but the stash in his saddlebags gave him a rare opportunity to be charitable.

“There’s no need,” he replied. “Can you ride?”

She shook her head. “I haven’t sat on a horse in ten years, Mr….?”

“Call me Jake.”

“I don’t know you well enough to use your given name.”

“You will soon enough.” With four dead mules and one horse, they’d be sharing a saddle and he’d be pressed up against her shapely backside for hours. With a lazy grin, he added, “Lady, you and I are going to be intimately acquainted before nightfall.”

Her eyes went wide, and beneath her thick lashes he saw dark circles of exhaustion, sheer terror and rage. Her loose hair caught the sun, and her eyes hardened into agate. “I doubt very seriously that’s going to happen.”

“Are you afraid of horses?”

She answered him with a glare and Jake eyed the bay, wondering how the animal would feel about the extra weight. From the corner of his eye, he saw her shift the baby and reach into her pocket, probably for a handkerchief to wipe away the day’s sweat. He pushed back his hat and blew out a hot breath as he turned to look at the angel.

“Do you think you can—”

A muddy Colt Peacemaker was aimed at his chest. Hell, she had hidden it in her pocket and he hadn’t noticed.

“Get out of here, or I swear I’ll shoot,” she said.

“Go right ahead. It’ll be a short trip to hell at this range.”

Her eyes flickered, and he knew she couldn’t possibly send a man to his death, let alone eternal damnation.

“Leave! Now!”

“I don’t want to.” The angel’s challenge pulled him in like a moth to a flame. “Lady, it’s just plain stupid to stay here. You might make it for a week or two, but Charlie there won’t.”