По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

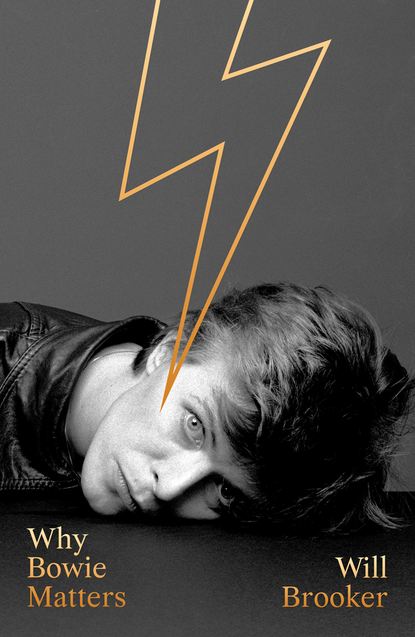

Why Bowie Matters

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Once more, we reach a point of recognition. Surely, now, Bowie has done it. This is the hit single we all know. This is the brink of fame. ‘Space Oddity’ would open the album most of us recognise as his first – it was also named David Bowie – after the false start of the Deram LP. Bowie himself, typically, wrote his debut out of history, claiming in a 1972 interview that ‘I was still working as a commercial artist then and I made it in my spare time, taking days off work and all that. I never followed it up … sent my tape into Decca and they said they’d make an album.’ According to the popular myth of Bowie, this is the real beginning. It’s worth freeze-framing him again here, and asking how he reached this point, after the crashing failure of 1967. How did he get past the disappointment, and retain his drive? Why did he keep trying?

We can only speculate, while acknowledging that every decision can have several motivations: a need to live up to Ken Pitt’s expectations and investment; perhaps a desire to please his dad, who, as Bowie told an interviewer in 1968, ‘tries so hard’ and still supported him; certainly, Bowie seemed to retain an almost untouchable core of self-belief. In a conversation with George Tremlett in 1969, he explained, ‘smiling but firm’, that ‘I shall be a millionaire by the time I’m thirty.’ Tremlett comments that ‘by the way he said it, I saw the possibility that he might not make it had barely crossed his mind.’ There is another possible reason, concealed within the frantic comedy of ‘The Laughing Gnome’, his single from 1967. This novelty song failed to make it onto the Deram LP, was reviewed at the time as ‘the flop it deserved to be’, and haunted Bowie’s subsequent career. Understandably, it remained part of the 1960s he’d rather forget.

But while its high-pitched vocals and Christmas-cracker jokes make it an even broader music-hall number than ‘Uncle Arthur’, it shares intriguingly similar motifs with Bowie’s other work of the time: a local high street, a quirky older character, threats of authority (‘I ought to report you to the Gnome Office’), and forced exile via the railway station (‘I put him on a train to Eastbourne’). The narrator in ‘Can’t Help Thinking About Me’ leaves his family in ‘never-never land’, and sets out towards an uncertain future, ‘on my own’; the gnome is asked, ‘haven’t you got a home to go to,’ and replies that he’s from ‘gnome-man’s land’, a ‘gnome-ad’. Like the ‘London Boy’ and ‘Uncle Arthur’, the gnome is drawn back from his wandering towards suburbia and home comforts: when the narrator puts him on a train to the coast, he appears again next morning, bringing his brother. Even the references to success, described in terms of eating well (‘living on caviar and honey, cause they’re earning me lots of money’) echo the rhyming contrasts between family security and precarious independence in ‘Uncle Arthur’ and ‘The London Boys’ (‘he gets his pocket money, he’s well fed’; ‘you’ve bought some coffee, butter and bread, you can’t make a thing cause the meter’s dead.’) Behind the frenetic gags, ‘The Laughing Gnome’ explores the same tension as Bowie’s more anguished singles from the same period: the push and pull of comforting, dull safety versus risky adventure. The same dynamic recurs, more metaphorically, throughout his later work, and can even be seen to structure Bowie’s career; we’ll return to it later. Already, though, we can see that this song has more to it than meets the eye.

It’s easy to dismiss ‘The Laughing Gnome’ as a convenient vehicle for packing in as many gnome jokes as possible. But as we’ve already seen, Bowie was tempted by puns in his more serious tracks, too. ‘Rubber Band’ may be frivolous, but ‘Maid of Bond Street’, also built around a play on words, isn’t meant to be funny. ‘Space Oddity’followed – ostensibly spoofing 2001: A Space Odyssey (the name ‘David Bowie’ even sounds like a parody riff on the movie’s protagonist, Dave Bowman) but far from a comedy song – and then ‘Aladdin Sane’, containing the hidden confession ‘A Lad Insane’. The cover of Low is a visual joke on ‘low profile’. ‘New Killer Star’, from 2003, puns on George W. Bush’s pronunciation of ‘nuclear’, but the song is no joke: it opens with a reflection on the ‘great white scar’ of the former World Trade Center.

In 1997, Bowie returned self-consciously to ‘grumpy gnomes’ with ‘Little Wonder’, which includes the names of the Seven Dwarves in its lyrics and has a twist in its title: depending on context, the phrase is used to imply both ‘no wonder, then’, and ‘you little marvel’. Linguistic gags in Bowie’s work are not, then, a cue for us to disregard the song as meaningless cabaret. In fact, the hysterical surplus of double meaning in ‘The Laughing Gnome’ could even be seen as an invitation to read more into the lyrics, like a dream bursting with symbolism that begs for analysis. ‘Gnomic’, after all, also signifies a mysterious expression of truth, and leads us, in turn, to Bowie’s description for the mousy-haired girl in ‘Life on Mars’. In a 2008 article he called her an ‘anomic (not a “gnomic”) heroine’. He knew the word could be read in other ways.

If we accept that the song can be taken more seriously, then the gnome’s brother, who appears at the end of the narrator’s bed one morning, is the key to further interpretation. David Jones had, more than once, woken up to find his half-brother, Terry, back from his nomadic travels and sharing his bedroom. Terry was ten when he first joined the Jones family at Stansfield Road in Brixton; but when they moved to Bromley in 1953, Terry, who hated John Jones, stayed behind. In June 1955 he came back, taking the bedroom next to David’s on Plaistow Grove; in November, he left again for the air force, and didn’t return for three years. He couldn’t stay, Peggy explained when Terry turned up again, unkempt and disturbed – the back bedrooms had been merged into one, and there was no room – so he moved out to Forest Hill, but still caught the bus regularly to Bromley, to visit David. Terry was already a major influence on his younger half-brother, helping him, as Peter and Leni Gillman put it, to ‘discover a new world beyond the drab confines of the suburbs’. He took David to jazz clubs in Soho, gave him a copy of Kerouac’s On the Road, and encouraged him towards saxophone lessons. ‘I thought the world of David,’ he later said, ‘and he thought the world of me.’ An intermittent resident at Plaistow Grove over the next decade, Terry was also in and out of local hospitals for the mentally ill. He was developing schizophrenia.

In February 1967, David and Terry – now both adults – walked down to the Bromel Club to see Cream in concert. ‘I was very disturbed,’ Bowie later recalled, ‘because the music was affecting him adversely. His particular illness was somewhere between schizophrenia and manic depressiveness … I remember having to take him home.’ According to Buckley’s biography, Terry ‘began pawing the road’ after the gig. ‘He could see cracks in the tarmac and flames rising up, as if from the underworld. Bowie was scared witless … this example of someone so close being possessed was horrifying.’ He was, Buckley goes on, ‘frightened that his own mind would split down the middle, too’. Bowie’s own recollection is, as we’ve seen, less melodramatic, but he confirmed in another interview, with a formality that suggests he was choosing his words carefully, that ‘one puts oneself through such psychological damage trying to avoid the threat of insanity, you start to approach the very thing that you’re scared of. Because of the tragedy inflicted, especially on my mother’s side … that was something I was terribly fearful of.’ His grandmother, Margaret, had also suffered from mental illness, as had his aunts Una, Nora and Vivienne; Terry’s episode at the Bromel Club brought it closer to home, though it’s worth noting that cousin Kristina dismissed Terry’s experience as a ‘bad acid trip’, and the idea of insanity in the family as one of David’s long-term lies, or ‘porkies’. ‘It just wasn’t true,’ she told Francis Whately in 2019.

Terry features obliquely in at least two of Bowie’s songs. ‘Jump They Say’ (1993), Bowie explained, was ‘semi-based on my impression of my stepbrother’; he was cagier about ‘The Bewlay Brothers’ (1971), throwing out various decoy explanations before admitting, in 1977, that it was about himself and Terry, with ‘Bewlay’ as an echo of his own stage name. ‘The Laughing Gnome’ is never discussed in this context – it is, at best, accepted by critics as a bit of fun, or in the words of Peter and Leni Gillman, ‘a delightful children’s record’ – but it’s tempting to add it to the list of songs inspired by Bowie’s half-brother, especially if we bear in mind a story that Kristina tells about Terry and their grandmother. Little Terry had nervously smiled after being scolded. ‘Nanny said, “Go on, laugh again,” and he smirked again, and she smacked him across the ear and said, “That’ll teach you to laugh at me.”’ Ha ha ha. Hee hee hee.

It’s a persuasive reading. But to label ‘The Laughing Gnome’ with a single interpretation – a song about Terry Burns, the manic outsider who kept turning up at David’s house, and was sent away – would be reductive. Any Bowie song is, like the man who wrote it, a matrix of information, with multiple possible patterns of connection. Even single words can be loaded, and can pivot in various directions, suggesting different links. We can join the dots of those words and phrases in several ways and create a convincing structure, but with a twist, and from a new perspective, the picture changes. As I’ve suggested, ‘The Laughing Gnome’ also explores Bowie’s to-and-fro tension between independent adventure and the security of home. It’s also, let’s face it, a comedy song, a novelty number, a ‘delightful children’s record’. It can be all those things and more. An interview with novelist Hanif Kureishi gives a further quick twist and suggests a final angle.

Kureishi recalls that, when they worked on Buddha of Suburbia together, Bowie ‘would talk about how awkward it was in the house for his mother and father when Terry was around, how difficult and disturbing it was’. But he immediately goes on, without changing the subject, to describe his own experiences with Bowie on the phone. ‘I got the sense you have with some psychotic people when they’re just talking to themselves. It’s just a monologue, and he is just sharing with you what’s going round and round in his head.’ From Terry’s schizophrenia to David’s seeming psychosis, without a jump: the seamless segue is telling, and it’s a short step from there to Chris O’Leary’s suggestion that ‘The Laughing Gnome’ is ‘a man losing his mind, a schizophrenic’s conversation with himself’.

It would seem overly simplistic to suggest that Bowie channelled a fear of insanity directly into his work – ‘All the Madmen’ (1970), for instance, or the ‘crack in the sky and the hand reaching down to me’ from ‘Oh! You Pretty Things’ (1971) – unless he’d admitted it himself. ‘I felt I was the lucky one because I was an artist and it would never happen to me because I could put all my psychological excesses into my music and then I could be always throwing it off.’ This confession, included in Dylan Jones’sbook, follows directly on from the quotation above (‘one puts oneself through such psychological damage …’). Note how Bowie’s formal poise switches into a rushed incantation; an attempt to make something true by saying it quickly.

In this sense, then, ‘The Laughing Gnome’ is not just about Terry, but about what Terry meant to his younger half-brother: a troubled alter-ego who always comes back when he’s sent away, a reminder of what Bowie could have been, and what he feared he could still become. The laughing gnome is a figure embodying both madness and truth: manic laughter and gnomic warnings. You can’t catch him, and you can’t get away from him. He can’t be successfully repressed, but he can be accepted and embraced, not just peaceably but profitably (‘we’re living on caviar and honey, cause they’re earning me lots of money’). If we follow this interpretation to its conclusion, Bowie was not just pushing himself because he hungered for fame. He was driven to keep creating because he wanted to expel the ideas from his head into his art; he preferred to make the hallucination into a comedy character, rather than hear that high-pitched chuckling confined to his own head. He wanted to exorcise the energy before it could drive him crazy. He felt his art would save him, and perhaps it did; as the song predicts, it certainly earned him success.

Was his creative drive really fuelled, at least in part, by this fear of mental illness? We can’t be sure: we can only try to read back through Bowie’s public art into his private motivations, using the facts of his life as a framework. But it’s a valid way of seeing, and it makes a good story.

Bowie kept trying, despite all the setbacks, and kept working, and kept moving. After another brief stay at Plaistow Grove in January 1969, he’d relocated to 24 Foxgrove Road in Beckenham, which he shared with Barrie Jackson, a childhood friend from his old street. The following month he moved in with Mary Finnigan, in the ground-floor flat of the same house. His relationship with Finnigan quickly changed from neighbours to lovers, and then adapted again when he met Angie Barnett on Wednesday 9 April. In August, David and Angie moved to Haddon Hall, at 42 Southend Road, Beckenham, where they rented the entire ground floor of a Victorian villa.

Both Haddon Hall and 24 Foxgrove Road have been demolished and replaced with flats. You can still visit both sites, though, and realise how close they are to each other; Foxgrove Road is five minutes up the hill from Beckenham Junction Station, and 42 Southend Road less than ten minutes’ further walk in the same direction. Beckenham Junction, in turn, is just two stops down the line from Bromley. Again, Bowie’s sense of adventure, experiment and escape was tempered with caution. He’d moved out of his parents’ home, and in with a neighbour from his childhood street; he then relocated downstairs with Mary Finnigan, making friends with her young children and becoming part of a new family household. When he finally rented his own place with a long-term girlfriend, he was still only a couple of miles from his childhood home; easily close enough for his mother to come round and prepare Sunday lunches for Bowie and his friends. Peggy later moved to a flat in Beckenham, even nearer to her adult son, and when Bowie and Angie married, they held the ceremony at Bromley Register Office, with the reception in the Swan and Mitre pub. However, while Haddon Hall was only a few miles from Plaistow Grove, it was a world away from the tiny terraced house where David had grown up: a gothic playground with a grand piano, stained-glass windows, heavy oak and crushed velvet upholstery. Bowie and Angie would go out to clubs together and bring dates back; band members slept on mattresses across the landing, and the basement was converted into a rehearsal studio.

Finally, he’d found what he’d been working towards. His former lover Mary had made friends with his new girlfriend Angie; he invited his friend, producer Tony Visconti, to move in with them. Together, David and Mary Finnigan developed an Arts Lab at the Three Tuns, down the hill on Beckenham High Street. Bowie was the star act, backed by psychedelic liquid light shows, and the audience reached over two hundred during the summer. They organised an open-air festival for the same day as Woodstock, at Croydon Road Recreation Ground (the bandstand is still there). Bowie started to record a new album in July, and released ‘Space Oddity’ as a single on 11 July, in time to catch the buzz around the moon landing. John Jones wrote to Ken Pitt that ‘David is keeping very cheerful and seems to be keeping himself fully occupied.’ It was summer 1969. After seven years of trying, Bowie had made it.

But there was another heavy blow in his step-by-step progress towards greater independence. His move into Haddon Hall immediately followed the death of John Jones, at age fifty-six, on 5 August. Bowie had just returned from a festival in Malta, and had come back in time to perform at the Arts Lab. Mary Finnigan informed him after the set that his father was seriously ill, and Bowie arrived at Plaistow Grove to find him semi-conscious. He struggled through the Free Festival, in what he understandably called ‘one of my terrible moods’. Later, he explained that he’d lost his father ‘at a point where I was just beginning to grow up a little bit and appreciate that I would have to stretch out my hand a little for us ever to get to know each other. He just died at the wrong damn time …’

‘Space Oddity’ started slowly in the chart, then rose to number 25, earning Bowie his first appearance on Top of the Pops in early October. The single reached number 5 at the start of November, the perfect lead-in to his second album on Friday 14 of that month. With a youthful mixture of humility and arrogance, Bowie told the NME,‘I’ve been the male equivalent of a dumb blonde for a few years, and I was beginning to despair of people accepting me for my music. It may be fine for a male model to be told he’s a great looking guy but that doesn’t help a singer much.’ In early 1970 he formed a new band, the Hype, teaming up for the first time with guitarist Mick Ronson and drummer Woody Woodmansey. The team we know as the Spiders from Mars was almost entirely in place, adopting larger-than-life stage personae (‘Spaceman’, ‘Hypeman’, ‘Gangsterman’): with hindsight, it looks like the start of glam rock. And then in March 1970 Bowie released his follow-up to ‘Space Oddity’, ‘The Prettiest Star’. It sold 798 copies and died. He wouldn’t have another hit single for two years. He hadn’t made it after all.

I sat in the Zizzi on Beckenham High Street, which is now decorated with a mural of Bowie and key quotations from his songs in the windows. At the next table, three teenage lads ordered bashfully from a blonde waitress, in front of the lyrics ‘When you’re a boy, you can wear a uniform; when you’re a boy, other boys check you out.’ Fifty years ago, Bowie sat here with his acoustic guitar, playing for a crowd of regulars. This Zizzi was the Three Tuns until 1995, then the Rat and Parrot. In 2001, Mary Finnigan and supporters installed a plaque celebrating the Arts Lab and anticipating that the pub’s former name would be restored: it was, but only for a year. The plaque is still out front, with its perhaps overambitious boast that Bowie launched his career here; a Three Tuns sign hangs alongside the Zizzi logo.

It’s hard to know the truth about any period in Bowie’s life. Some stories are built on more solid foundations, and some are shakier. The popular idea that Bowie shocked the world in the early 1970s as a fully-formed genius makes him easier to idolise, perhaps, but harder to aspire to, and harder to identify with. It is easier to treat him as a creature of uncanny talent, an unearthly one-off, because it erases the years of struggle behind his success and allows us to think of him as different to the rest of us. But in many ways, he wasn’t different to the rest of us. He wasn’t trained as a singer. He didn’t show early signs of musical ability. He was an uncertain frontman as a teenager, insecure about his own vocal abilities. You can hear him improving from single to single during the 1960s. He taught himself saxophone at the age of fifteen, learning to play along with his favourite records, and focused on it while he was convalescing from his eye injury: he took lessons, but only from spring until summer 1962. He could pick out chords on a guitar and piano, but couldn’t read or write music; he used descriptions in a book to choose the instruments for his debut album, and relied on colour-coded charts, instead of conventional notation, for ‘Space Oddity’. As a dancer, an artist and an actor he was an enthusiastic amateur. He had the privileges of being a white, lower-middle-class teenager in a little house in a safe neighbourhood; but he also had to deal with a troubled half-brother who clashed with his parents, a family history of mental illness and the early loss of his father.

In September 1972, David Jones sailed with his wife Angie to New York on the QE2. He was now not just David Bowie, but Ziggy Stardust, complete with the crimson hair, jumpsuits and platform boots. They checked into the Plaza Hotel on Central Park and went up to their suite. ‘Babe,’ said Angie – or so the story goes – as she looked around at the decor, the view and the gifts from the production company, ‘we’ve made it.’

Вы ознакомились с фрагментом книги.

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера:

Приобретайте полный текст книги у нашего партнера: