По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

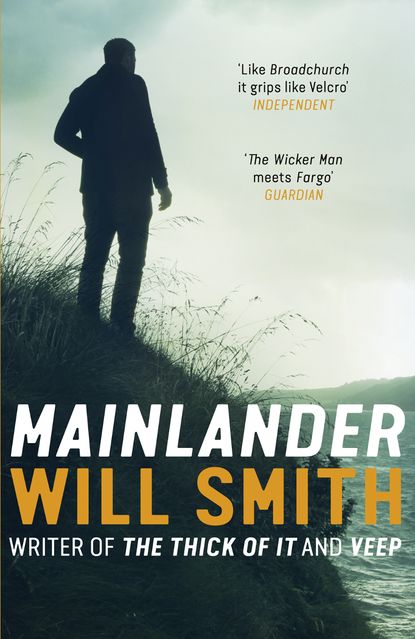

Mainlander

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘I hadn’t thought of that. I get so confused by what holidays they have, these days. Not like in my day …’

‘Wonder how he knew our address.’

‘Well, it’s an odd name. Only one in the phone book.’

‘I suppose. Thanks again.’

‘Let me know if you’re feeling up to a cup of tea later. I bought some currant buns at the market that need eating up …’

Emma had shut the door.

4 (#ulink_df48af0a-bb85-5866-b9da-dffd5391b0b6)

LOUISE (#ulink_df48af0a-bb85-5866-b9da-dffd5391b0b6)

Saturday, 10 October 1987

The first coffee had pierced the fug of her hangover. The second had helped her assemble the jumbled pieces of the previous night. The third unbuttoned the Scouse lip that Louise O’Rourke had used sparingly since she’d come to the Island.

She had held back yesterday morning when she’d been fired from the Bretagne halfway through her first day. Initially this was because she was reeling from the shock. She had just about got used to the fact of having landed a job at one of the Island’s top hotels, the first rung on a ladder that would take her to higher levels previously denied. For a moment she had thought she was about to cause a monumental scene, but as she processed what was happening she decided on a cannier move.

Though she knew him by name and reputation, she had not met Rob de la Haye before she started working on the front desk of his hotel. She’d caught his eye as he walked up the main staircase that Friday morning, but she had recognised him as Doug, the yacht salesman, ‘in the Island for one night only’, who had bedded her at the end of a day’s carousing at the Bouley Bay Hill Climb in July, an annual event in which bikes and cars took turns to roar up the tree-fringed bends from the harbour to the top of the bluffs.

She hadn’t been sure it was the same man so once she’d finished dealing with a guest she had checked the register for anyone staying named Doug or Douglas. There was none. Later that morning the inscrutable Christophe had taken her into his manager’s office and told her that, due to circumstances beyond his control, he would have to ask her to leave. He offered her three months’ wages, a glowing reference and a hint to refrain from pursuing the matter, which she declined to take.

‘Shame. I never even got to meet Mr de la Haye. Or his wife.’ She still wasn’t sure whether Rob was the man she had slept with.

‘I could make it six months’ wages, if your need to meet Mr de la Haye or his wife were to disperse.’ That was all the confirmation she needed.

She’d taken the money, met some friends at lunchtime, told them she’d jacked in her job after a modest win on the local lottery that would see her right for a while, and drunk the day away. Her friend Danny had joined her for last orders once he’d finished his kitchen shift and they’d sat on the walkway that led out to the Victorian tidal bathing pool at Havre des Pas. It was opposite the café outside which she now sat, insulated from the fresh October air by her body-warmer, and a stagger away from the bedsit where she’d been woken by sunlight streaming through the dip in the sheet that hung as a makeshift curtain. It hadn’t helped her mood to find Danny on the floor; that meant they’d started off sharing the bed platonically, then he’d either mentioned the L-word or had started grinding against her with an erection while they were spooning. Either way, she’d literally kicked him out of bed. He had a characteristic that marked him out from other men she had known, which drew her to him as a friend but repelled her as a lover: dependability. She’d enjoyed sleeping with him initially, but she was not conditioned to be attracted to men who posed no challenge, so had made it clear some months ago that they were to proceed as friends. He’d protested but they had stuck to it without any tension, except on those odd occasions when Louise had been drunk on the wrong side of the Island at midnight without a taxi fare and they’d ended up sharing a bed. Her girlfriends had taken to referring to him as ‘Danny Doormat’, which she resented. If he chose to put her on a pedestal and make an unasked-for pledge of romantic servitude, that was his look-out. She’d made clear to him where they stood.

The café was starting to fill for lunch. A family of four stood on the pavement, the parents eyeing the menu with distaste.

‘It’s a rip-off place for visitors. I mean, look at the people,’ muttered the father, in peach-coloured linen trousers and boat shoes. Louise looked around at the out-of-season tourists. They were her kind of people: Mancs, Scousers, Scots, working-class families in search of a bit of sun in a place where you could order a decent cup of tea in your own language.

‘Oh, please, I’m starving,’ moaned the elder son, lanky for his age.

‘You said it was our choice, Dad, and this looks fine,’ put in the daughter.

‘There’s no room anyway,’ said the mum, whose taut features were mostly hidden behind a pair of outsize sunglasses.

‘I’m going if you’re looking for a table,’ piped up Louise, broadening her accent to intensify the awkwardness.

‘Oh, no, we’re fine, actually,’ replied the dad. ‘We’re running late for a thing anyway …’

‘They serve really quick,’ said Louise, getting up. ‘Hey, Mick, I’m leaving two quid for the coffees. This lovely family needs to eat and go!’ A waiter in his fifties with smeared tattoos on his forearms and a beer belly like a balloon came straight over with menus and ushered the family, who were divided between relief and annoyance, to their seats.

‘I recommend the chip butty,’ Louise added perkily, as she passed the mum, who looked the type to wonder why ten minutes a week in front of the calisthenics video didn’t shift the pounds accrued at aimless social teas.

She crossed the road and stood at the railing, looking down at the beach. The dark blue water was smooth and gelatinous. She inhaled deeply. She loved the saline scent that permeated the perimeter of the Island. Very different from the stench of the diesel-skimmed brown water that lay in the port of her home city. The sound of the wash was calm and hypnotic. It wasn’t the kind of tide that felt like it was trying to take the Island, unlike the late-autumn swells that beat over the edge of the sea walls. It was nuzzling the sand about twenty feet down from where the high tide had left a rim of seaweed. She looked at her watch. Midday. Twelve hours earlier she and Danny had bought a bottle of whisky from behind the bar and sat on the walkway staring down at the reflections of the coloured bulbs strung above that glinted in the roll of the black water. She had found herself admitting to him that she had been sacked. She regretted telling him the specifics: mention of her sleeping with another man reinforced the boundaries of their relationship, but he spiralled into a monosyllabic gloom of hurt. She remembered ignoring this and declaring that Rob de la Haye would regret the fucking day he’d crossed her.

A toddler punctured her reverie by bursting into tears as a seagull attempted to mug him for his doughnut. She remembered crying last night. Fuck. Danny was so loyal to her, carrying a torch that might have been mistaken for a lighthouse, that she tended to steel herself against the revelation of any vulnerability, but last night she had broken down, and he had put his arm round her. A pass dressed up as gallantry. He had made her a promise. She had talked about packing up and going home. The best a Mainlander like her could hope for was to serve at top table: she was never going to get a seat at it.

‘Get your own place then, like you wanted,’ Danny had slurred. When they first met, at the St Aubin hotel where she’d started as a cleaner, she’d talked of her grand plan to buy a little hotel or B-and-B and build up a business. Her fellow expats were happy to use the Island as a source of casual labour and casual sex, but not her. She didn’t like the way its people looked down their noses at her. Forty-three years ago and seventy-one miles away her granddad had run up Normandy’s Gold Beach into the jaws of death while these petty Islanders were waiting out the war with nothing more to complain about than a shortage of sugar.

‘I’m not allowed to fucking buy here, Danny,’ she’d spat back. Her grand plan had been shattered: without local housing qualifications she wasn’t eligible to buy any property, commercial or private, until she had rented for twenty years. ‘I can’t wait till I’m forty-two.’

‘Use my quallies then.’

‘What are you talking about?’

‘We’ll do it together. You find the money, I’ll buy it for you.’

‘Buy what, though?’

‘The Crow’s Nest is for sale.’

‘How much?’

‘Sixty.’

‘So I’d need a six-grand deposit. Plus another four or so for the refurb. That place hasn’t been touched since the seventies. Anyway, that would make you my boss. I don’t think either of us could handle that.’

‘We’d be partners. Mine on paper only. I run the restaurant, you do the rest. And we split any sale fifty-fifty.’

‘Oh, Christ, Danny. This is some weird future fantasy you’ve worked out. How many times? I don’t need you to save me.’

‘I’m looking at it as a business proposition. You’re bright, Lou, brighter than me. And tougher. I don’t want to spend my life chopping carrots and reheating shepherd’s pies so some hotelier can own three cars and a pool, but that’s all I’ve got ahead of me. You can pull me out too.’

‘Pull you out of what? You’re Jersey born and bred. You’re fine.’

‘We’re not all fucking millionaires and tax exiles. Some of us work bloody hard, same as your lot.’

‘Do not compare yourself to my lot. My lot have been shat on. How many of your school-friends have been stabbed or banged up?’

She started to feel hungry so opened her purse to check how much cash she had left. She found two pounds and a scrap of paper scrawled with Le Petit Palais, La Rue de Grassière, Trinity. Rob’s home address. She had surreptitiously obtained it from the office before she left the Bretagne. She hadn’t known why. A vicious letter to his duped wife? An anonymous threat? A dog turd in a box? She looked back at the café where the parents of the local family were wolfing their food, the wife clutching her handbag on her lap rather than risk putting it on the floor against her chair. What did she expect would happen? That it would be hooked and tossed into the throng of the great unwashed who would close ranks like a League of Thieves from a nineteenth-century romance? This Island had branded her since she had first touched down, a two-star accent in a five-star town: Scousers were thieves, untrustworthy. Very well, if that’s what the Island wanted, maybe that’s what the Island should get.

She strode back to her bedsit and used the communal phone in the hall to dial a cab, then went back to her room and took a tenner from Danny’s wallet, leaving him an IOU and a promise to be in touch in the week.

On the way into the belly of the Island, sunbeams darted through the spindly branches of the wind-stripped trees, adding to her headache. She shifted to the other side of the car and wound down the window to let the cool breeze enliven and narrow her sense of purpose. This had the bonus of drowning out the insinuations of the prying local driver.

‘Friend’s house?’

‘Yeah, going for lunch.’

‘Nice houses round there.’

She wanted to say, ‘Keep the car running while I rob them,’ but settled for ‘Hm.’