По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

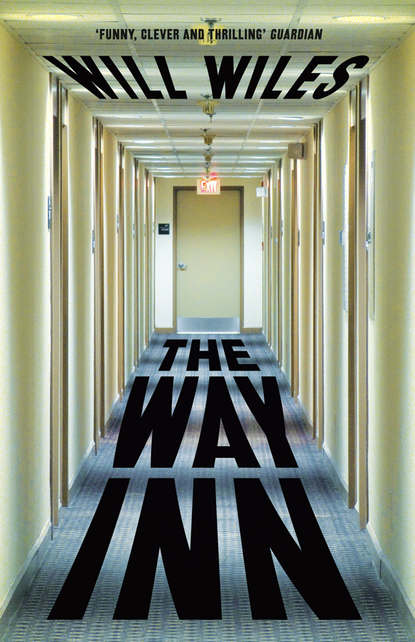

The Way Inn

Автор

Год написания книги

2018

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘So, Tom, why are you here?’

He jutted his bottom lip out and made a display of considering the question.

‘A friend told me about your service, and I wanted to find out more about it.’

Word of mouth, of course – we don’t advertise.

‘I meant,’ I said, ‘why are you here at the conference? Aren’t there places you would rather be? Back at the office, getting things done? At home with your family?’

‘Aha,’ Tom said. ‘I see where you’re going.’

‘Conferences and trade fairs are hugely costly,’ I said. ‘Tickets can cost more than £200, and on top of that you’ve got travel and hotel expenses, and up to a week of your valuable time. And for what? When businesses have to watch every penny, is that really an appropriate use of your resources?’

‘They can be very useful.’

‘Absolutely. But can you honestly say you enjoy them? The flights, the buses, the queues, the crowds, the bad food, the dull hotels?’

Tom didn’t answer. His expression was curious – not interested so much as appraising. I had an unsettling feeling that I had seen him before.

I continued. ‘What if there was a way of getting the useful parts of a conference – the vitamins, the nutritious tidbits of information that justify the whole experience – and stripping out all the bloat and the boredom?’

‘Is there?’

‘Yes. That’s what my company does.’

I am a conference surrogate. I go to these conferences and trade fairs so you don’t have to. You can stay snug at home or in the office and when the conference is over you’ll get a tailored report from me containing everything of value you might have derived from three days in a hinterland hotel. What these people crave is insight, the fresh or illuminating perspective. Adam’s research had shown that people only needed to gather one original insight per day to feel a conference had been worthwhile. These insights were small beer, such as ‘printer companies make their money selling ink, not printers’ or ‘praise in public, criticise in private’. But if Graham got back from a three-day conference with three or four of those ready to trot out in meetings, he’d feel the time had been well spent. That might sound like a very small return on investment, and it is, but these are the same people who will happily gnaw through cubic metres of airport-bookshop management tome in order to glean the three rules of this and seven secrets of that. Above those eye-catching brain sparkles, a handful of tips, trends and rumours is all that sticks in the memory from these events, and they can get that from my report, plus any specific information they request. Want to know what a particular company is launching this year? Easy. Want a couple of colourful anecdotes that will give others the impression you were at the event? Done. Just want to be reassured that you didn’t miss anything? My speciality.

And if you want to meet people at the conference, be there in person, look people in the eye and press the flesh – well, we can provide that as well. I’ll go in your place. Companies use serviced office space on short lets, the exhibitors here have got models standing in for employees and they use stock photography to illustrate what they do. That pretty girl wearing the headset on the corporate website? Convex can provide the same professional service in personal-presence surrogacy. We can provide a physical, presentable avatar to represent you. Me. And I can represent dozens of clients at once for the price of one ticket and one hotel room, passing on the savings to the client.

Of course I still have to deal with the rigmarole of actual attendance, but the difference is that I love it. Permanent migration from fair to fair, conference to conference: this is the life I sought, the job I realised I had been born to do as soon as Adam explained his idea to me, at a conference, three years ago. It is not that I like conferences and trade fairs in themselves – they can be diverting, but often they are dreary. In their specifics, I can take them or leave them – indeed, I have to, when I am with machine-tools manufacturers one day and grocers the next. But I revel in their generalities – the hotels, the flights, the pervasive anonymity and the licence that comes with that. I love to float in that world, unidentified, working to my own agenda. And out of all those generalities I love hotels the most: their discretion, their solicitude, their sense of insulation and isolation. The global hotel chains are the archipelago I call home. People say that they are lonely places, but for me that simply means that they are places where only my needs are important, and that my comfort is the highest achievement our technological civilisation can aspire to. When surrounded by yammering nonentities, solitude is far from undesirable. Around me, tens of thousands are trooping through the concourses of the MetaCentre, and my cube of private space on the other side of the motorway has an obvious charm.

Tom Graham appeared to be intrigued by conference surrogacy, and asked a few detailed questions about procedures and fees, but it was hard to tell if he would become a client or not. And if he did sign up, I wouldn’t necessarily know. Discretion was fundamental to Adam’s vision for our young profession – clients’ names were strictly controlled even within the company, as a courtesy to any executives who might prefer their colleagues not know that someone was doing their homework for them. Today, for instance, I knew that clients had requested I attend two sessions, one at 11.30 and one at 2.30, but I had no idea who or why. After the second session, my time would be my own – I could slip back to the hotel for a few hours of leisure before the party in the evening.

A few hours of leisure … The thought of my peaceful room, its well-tuned lighting, its television and radio, filled me with a sense of longing, the strength of which surprised me. It was almost a yearning. Right now, I imagined, a chambermaid would be arranging the sheets and replacing the towel and shower gel I had used. Smoothing and wiping. Emptying and refilling. Arranging and removing. Making ready.

Also, a return to the hotel would give me another chance to encounter the redheaded woman – a slim chance, but it was an encounter I was ever more keen to contrive. Her continual reappearance in my thoughts was curious to me, and almost troubling – a sensation similar to being unsure if I had locked my room door after I left. Her shtick about the paintings might have been a sign that she was a miniature or two short of a minibar, but it had only increased her mystique. She was unusual – of course, that had been obvious the first time I saw her, years ago. Beautiful, too. And there was something about the rapture with which she described the potential of the motorway site, its existence at the nexus of intangible economic forces … she knew these places, she had some deeper understanding of them.

After I had said my goodbyes to Tom and left the muffled solemnity of the Grey Labyrinth, the jangling noise and distraction of the fair were unwelcome, so I fled into the conference wing to find the first session. There, I found some peace. The seats were comfortable, the lighting was dimmed for the speaker’s slides. It was straightforward stuff: business travel trends in the age of austerity. I jotted down a few of the facts and statistics that were thrown out. Tighter cashflow, fewer, shorter business trips and less risk-taking meant potential gains for the budget hotels. Michelin stars in the restaurant and the latest crosstrainers in the gym were much less important than reliable wifi, easy check-in and a quiet room. Good times for Way Inn, and for me. It was reassuring, almost restful, stuff. For some of the session, I was able to come close to drowsing, letting my eyelids become heavy and enjoying being off my feet. The end of the talk was almost a disappointment. Applause was hearty.

I was beginning to feel that a peaceful routine had been restored – a sensation that was a surprise to me, because until that point I had not realised that my routine had been disrupted. Maybe I wasn’t getting enough sleep. Maybe, instead of pursuing Rosa or the redheaded woman into the night, I should get to bed early, spend some quality time in the company of freshly laundered hotel linen.

But first, lunch. There were various places to eat in the MetaCentre, and like an airport or an out-of-town shopping centre – anywhere with a captive audience, in fact – they were all likely to be overpriced and uninspiring. Rejecting branded coffee shops and burger joints, I headed for the main brasserie. In less image-conscious times, this would simply be called a canteen: big, bright and loud, serving batch-prepared food from stainless-steel basins under long metres of sneezeguard. A hot, wet tray taken from a spring-loaded pile and pushed along waist-height metal rails; a can of fizzy drink from a chiller, a cube of moussaka from a slab the size of a yoga mat; green salad in a transparent plastic blister. It might sound awful, but it was fine, really, just fine. I was eating alone and had no desire to linger – there was no need for me to be delighted by exotic or subtle flavours, and any attempt to pamper me would surely have been a delay and a provocation. It was good, simple, efficient, repeatable, forgettable. For entertainment, I sorted through some of the fliers and cards I had picked up from the fair. To carry these, I had brought my own tote bag, one from a fair last year which had unusually low-key branding. In my line of work, you never run short of totes.

In the MetaCentre’s central hall, even within the perplexing grid of the fair, navigation was not too hard: giant signs suspended from the distant ceiling identified cardinal points, and if you somehow managed to really, truly lose your sense of where you were, you could simply walk towards the edge of the hall and work your way around from there. In the wings of the centre, formidable buildings in themselves, a little more spatial awareness was needed. To find the venue of the second session on my schedule for the day, I had to consult one of the information boards that stood helpfully at junctions in the miles of passage and concourse. Before me, the conference wing was sliced into its three floors, splayed out like different cuts at the butcher’s and gaily colour-coded. I began to plot my course from the brasserie to the correct auditorium: Meta South, east concourse, S3 escalators …

This locative reverie was obliterated by a hard, flat blow between my shoulder blades, delivered with enough force to knock the strap of my tote bag from my shoulder. I wheeled around, part ready to launch a retaliatory punch even as I experienced sheer unalloyed bafflement that anybody could be so assailed in a public place, in daylight. What greeted me was a wobbly smile, wrinkled linen and strands of blond hair clinging to a pink brow.

‘Afternoon, old chap. I say, I didn’t take you off guard, did I?’

‘Jesus, Maurice,’ I said. ‘What the hell do you think you’re playing at?’

Maurice put up his hands. ‘Don’t shoot, commandant!’ He chuckled, a throaty, rasping gurgle. ‘Don’t know my own strength sometimes, it’s all the working out I do.’ Comic pause. ‘Working out if it’s time for a drink!’ The chuckle became a smoker’s laugh, and he broke his hands-up pose to wave me away, as if I was being a priceless wag.

‘You startled me,’ I said, stooping to pick up my bag.

‘So what’s in store next?’ Maurice asked, leaning over me to examine the map. I became uncomfortably aware of the proximity of my head to his crotch. The crease on his trouser legs was vestigial, its full line only suggested by the short stretches of it that remained, like a Roman road. ‘You going to “Emerging Threats”?’

‘Yes,’ I said, straightening. I wanted to curse. Trapped! It would be impossible to avoid sitting next to Maurice, and there was no way to skip it: ‘Emerging Threats to the Meetings Industry’ had, after all, been requested by a client. Sitting next to Maurice meant having to put up with his fidgeting, lip-smacking and sighing, and a playlist of either witless asides or snores. It had all happened before. And afterwards he would ask what I was doing next and if I said I was going back to the hotel there was a very real risk he would think that a fine idea and decide to follow me, and we would have to wait for a bus together and sit on it together, or I would have to spend time devising an escape plan, inventing meetings and urgent phone calls … the amount of additional energy all this would consume was, it seemed to me, almost unbearable. I wanted to lock the door of my hotel room, lie on the bed and think about nothing.

‘Bit of time, then,’ Maurice said, looking at his watch. ‘I’m glad I ran into you again actually, there’s something I keep forgetting to ask you. Do you have a card?’

‘Excuse me?’

‘A card, a business card. I’m sure you gave me one ages ago but’ – he rolled his eyes in such an exaggerated fashion that his whole head involved itself in the act – ‘of course I lost it.’

For a moment I considered denying Maurice one of my cards – it would be perfectly easy to claim that I hadn’t brought enough with me that morning and had already exhausted my supply – but I decided such a course was pointless. The cards were purposely inscrutable and were intended to be given out freely without concern. Just my name, the company name, an email address, a mailing address in the West End and the URL of our equally laconic website. I gave Maurice a card. He made a show of reading it.

‘Neil Double, associate, Convex,’ Maurice recited in a deliberately grand voice. ‘Ta. What is it you do again?’

‘Business information,’ I said. I am quite good at injecting a bored note into the answer, to suggest that nothing but a world of tedium lay beyond that description.

Maurice blinked like an owl. ‘What does that entail?’ he asked. ‘I’m sure you’ve told me all this before, sorry to be so dense, but I don’t think I’ve ever really got a firm handle on it. Strange, isn’t it, how you can know someone for years and never be clear what their line of work is?’

I smiled. There was no risk. ‘Aggregating business data sector-by-sector for the purposes of bespoke analysis.’

‘Right, right …’ Maurice said, his vague expression indicating I had successfully coated his curiosity with a layer of dust. ‘Great … Well, we had better get moving, I suppose. Aggregating to be done, eh?’

We started our trek towards the lecture hall. People streamed along the MetaCentre’s broad concourses and up and down the banks of escalators, redistributing themselves between venues. Homing in on the right room, narrowing the range of possible destinations, finding the right level, the right sector, the right group of facilities, I felt a rush of that peculiar, delightful sensation that comes in airports sometimes: of being an exotic particle allowed to pass through layers of filters, becoming more refined. Except that Maurice, a lump of baser stuff, was tagging along after me. And all the way, he kept up a monologue – inane business gossip, his opinions of the MetaCentre, what else he had seen that day and what he thought about it.

The lecture hall was larger than the previous one, with ranks of black-upholstered seats fanning out from a modest stage, where chairs and a lectern were set up. Almost half the seats were taken when we arrived, well ahead of the starting time, and most of the remainder filled as we waited for the session to begin. There was an expectant babble of conversation, although I wondered if that might be more due to the fact that everyone had just eaten – or drunk – their lunch, rather than due to any treat in store. I took the schedule from the information pack in my bag and examined it again, to see if there was anything particularly alluring about the talk. The title, ‘Emerging Threats’, was so ill-defined that it might have lent the event broad appeal. Next to the listing was the logo of Maurice’s magazine, Summit – it was a sponsor. He hadn’t mentioned that. I glanced at Maurice, who had seated himself next to me. He was staring into space, mouth slightly open, notebook and digital recorder on his lap. Like me, apart from the open mouth. He was uncharacteristically quiet, even focused.

Electronic rustling and bumping rose from the audio system: the three speakers had arrived on the stage and were being fitted with radio microphones. I closed my eyes and wondered how much of the discussion I could pick up through a drowse if I let myself slip into one. A grey-haired man was introducing the speakers – the usual panel-fodder from think tanks and trade bodies; middle-aged, male and stuffy. One of whom was very familiar. It took me some moments to establish that I really was looking at the person I thought it was, and while I stared at him, he found my eyes in the audience and smiled at me. It was Tom Graham, hands interlaced in his lap, legs crossed, sleek with satisfaction.

‘Last of all,’ the master of ceremonies said, reaching Tom, ‘a man who really needs no introduction – a fairs man through and through: Tom Laing, event director of Meetex.’

Applause.

‘Always the same old faces at these things.’

‘We must stop meeting like this.’

‘Small world.’

‘Groundhog day.’

‘Another day, another dollar.’

‘Are you here for the conference?’