По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

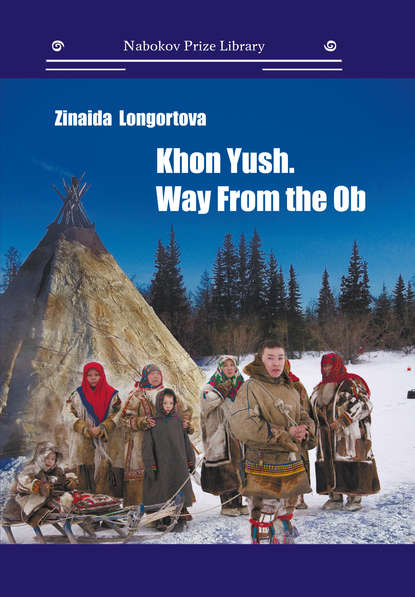

Khon Yush. Way From the Ob

Серия

Год написания книги

2020

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

„I wish. How are we going to spend the winter here?“

„Don't stand. Give me the cross, there's the guard coming. They can see it.“

She wrapped the knife and the cross in a piece of birch bark, and began digging the ground near the birch. At first, she threw wooden chips into the hole, and then put the gifts in the middle.

„Let's dig in. Quick, put the turf so that it's not visible,“ Pukan anki rushed her friend.

Having covered everything with earth and turf, women instantly grabbed shovels to make a dugout. Soon a guard came up and began to question:

„What did the old man want?“

„He said something, but we couldn't understand what he wanted. We thought he would go to the authorities, but he went to his place. Maybe he wanted to bring some fish, we don't know.

Maybe he scolded us that the girl was thrown. We don't understand his language.

„You fools, why did you open your mouths? Be silent about the child, otherwise I will send you further north.“

Women said, stumbling:

„Don't ask us! We did not see the baby“»

What and to whom could they say, bonded people of huge Russia under constant guard? Neither they had homes, nor the land, nor households – and nor rights. Their only goal was to save a man in themselves, not to become a beast in this remote taiga. Even this was hardly possible: every person those days thought only of his life, not of nobility. In order to survive, you needed to become slippery like a smelly burbot, slimy, toothy like a pike. But, as you know, pike and burbot always fall into the largest boiler. It's more convenient to cook large pieces of fish well.

It seemed that people lived on a deserted, god-forgotten land. The only ship on the Ob came once a month from afar. For thirty-forty kilometers from each other, you could find inconspicuous Khanty villages. In the small, dull gorts that were hidden near deep saimes, there were only two or three huts. The father's house – the clan's house, and, perhaps, the houses of older sons separated by age. However, every day at least one boat passed along the Ob banks, then another one sailed upstream. In good weather, light boats quickly disappeared behind the turn of the Ob, and on fishing boats, kayaks, that were stable on the waves, there were several people. Rowers struggled in three oars with the fast flow of the high-water As river, which had spread widely over the litter. It was good if they went down the river, but if they were sailing up, they had to stay close to the shore, where the current slowed down due to the shallow water.

No one was surprised when a few days later authorities approached the village. When people saw the boat arriving, they looked out of the doors and closed them again. There were attentive eyes looking from all the low windows of the huts and houses. District officials walked into the village council with a red flag fluttering. Soon the messenger boy ran to the houses, calling people to the gathering. Levne stepped out of the house with Anshem iki, looking around, and ran into the forest with the cradle. Anshem iki and his granddaughter went to the gathering. A high boss from the district stood next to the chairman, looking at the ignorant people who did not understand anything in the new life. He frowned, carefully examining people. Clearing his throat loudly, the guest spoke menacingly:

«Someone from your village took a newborn from exiled kulaks, from criminals. Who was it?»

The Khanty were silent as always. What could they say without knowing the Russian. Kurtan iki, the assistant chairman of the village council, wanted to get forward, but someone rudely pulled him back. A large man blocked him with his back and said loudly:

«Our babys here. Other baby no walk.»

«Baby no walk,» the newcomer from the district mocked, «so we have the newborn already walking!»

Someone convincingly spoke from the crowd:

«Hoyat baby holt tulev?»

Kurtan iki again began to get out of the crowd. He really wanted to help the authorities: they had important, necessary laws, but his fellow villagers didn't understand that a child of strangers had no place in the Khanty village:

«We have baby!»

«What? Where is the baby?» The visitor exclaimed.

«Turkoi kurt luti toock baby, mun at watsev nyavram!» Kurtan iki was painfully squeezed among the crowd, and went silent.

«That's ok, keep quiet! We'll check every home now. Chairman, take us to all the houses. Look at them! They decided to hide the children of the kulaks. Apples don't fall far from the tree.»

People were silent as they poorly understood Russian, but firmly held Kurtan iki.

The district authorities, along with the gloomy chairman, went with a family check. Anshem iki's neighbor, pushing into the back of the abiding Kurtan iki, headed towards the river. Kurtan iki resisted, but, fearing his cousin, continued to walk with him.

«If you live with bad thoughts, I'll drown you in the Ob,» the broad-shouldered man reprimanded the black-haired relative with cunning eyes. Kurtik iki was completely depressed from the frustration, lowering his shaggy head: he couldn't do a good deed for the authorities.

Kurtan iki was not liked in the village: he was envious, and the luck of his relatives never pleased him. Under the new government, he could compliment, almost bowing to every boss. He could slander anyone before him. He did this, of course, not for the benefit of himself, but for the benefit of the new government. He reported to his relatives, but received no gratitude from the authorities. They did not even thank him, but he already became addicted. Kurtan iki had nothing to do at the honorable work of the Russians, nor he went hunting like his brothers or other relatives. It seemed to him that his work was precisely in this, and it pleased him. What about the villagers? Constantly dissatisfied, illiterate. He didn't know how to write, but could sign documents. He didn't draw tamgu on paper – he wrote his name in letters.

Kurtan iki was the last child in a large family. His mother was fifty years old when she suddenly felt another heart beating under her heart. In their old age, his parents indulged their last child, allowing him whatever he wanted. While elder children helped around the house, went fishing, hunting, harvesting firewood and water, the favorite child played late until night with the neighboring children. The best pieces at the table went to the youngest, and he was used to taking it for granted. If only everything was done for him. Kurtan iki did not learn anything good from hardworking, kind parents.

Having looked at the work of the new authorities, who, without going into the forest for prey, without blood corns from oars, calmly earned money for bread, Kurtan iki was delighted. For Russians, those who have learned one or two letters were no longer illiterate. Therefore, he went to serve them, exposing himself to his superiors in every possible way. Soon he was appointed foreman. The bosses didn't need to catch fish, or get cold at a frozen ice-hole. Now he himself was the head of everything.

But no one envied him, although the new foreman dreamed of it. He envied everyone. His fellow villagers were indifferent to power. And his wife, silent Utiane, was not happy for him. She did not care if he was the boss or just her husband.

Noone knew who was to blame: the NKVD people or someone from the village who was informed about the newborn. The guards of the settlers was free. From time to time they came for fresh meat in the Khanty part of the village. They ate fish together, but someone, apparently, couldn't stop thinking of the baby born. But for some reason no one reported that they took a fresh catch from the population.

Finding nothing in Pitlourkurt, district authorities left for the next village to look for the unknown child. As soon as everything calmed down in the village, Anshem Iki went into the forest for his wife. Soon they returned home. The baby's face was smeared with mud and ash, although the little Tatar was no different from the Khanty children. They did it just in case: who would touch a dirty girl?

The authorities couldn't find the child, so soon they calmed down. How could one find a newborn in large Khanty families? Women gave birth according to ancient customs, in small clean houses specially set for mothers, with a bonfire that cleansed and warmed a woman in labor. You can't give birth in a house, it's a great sin. The child must be clean from all human sins and evil spirits.

There wasn't a single hospital within three hundred kilometers from the village. No Khanty woman in those years would dare to commit a terrible sin and let a doctor take birth. They had a midwife for this – and that was enough. The children were registered in the village council much later after the birth, while others were not taken into account by the Soviet government at all.

After the umbilical cord fell off at the little Tatar, women gathered at Anshem iki's house, bringing the children dressed up for the ceremony of initiation. Levne appointed mother assistants to the newborn girl – Pukan anki, Altam anki, Perna anki, and most importantly, according to the ancient custom, she thanked the goddess Kaltashch, to whom she dedicated her new child. It was she, Kaltashch Anki, who gave children to a family. Levne prayed to her, bowing her head in gratitude for the happiness of a fair-haired Tatar girl accidentally falling on her head:

«Long-braided, Golden Nye!

More beautiful than the sun, Golden Nye!

More beautiful than the beautiful, Golden Nye!

In a silk shawl colored like the morning dawn, whose long tassels are decorated with uncountable silver stars.

In the sable clothes, white kisas embroidered with the sacred ornament, sitting in your golden house in Heaven, goddess Kaltashch, you sent us a blessed day,» prayed Levne.

«My soul sings with happiness, and I thank you for the priceless gift, for the fair-haired daughter, who smiles with her ember eyes. I dedicate her soul to you. Take care of her, let her please us with her bright smile!» Grateful Levne bowed three times to the goddess.

«Your long braids are falling, Heavenly Nye, with a seven-fold silk sable from the mouth of the deep-water Ob to the Kara Sea itself. At night, under the moonlight and a thousand stars, your hair illuminates everything around. Even for our daughter moonlight and stars illuminate your face. On a clear day, your braids illuminate summer land covered with a green carpet, winter land with a white snow coat. Let the ends of your golden braids touch the head of our baby. Each of your fingers is wearing countless gold and silver, expensive and cheap rings – gifts of all the women of the Khanty land that gave birth or wish to have children. Take the ring from me too!»

At the sacred labaz, Levne laid a scarf with a silver ring tied in a corner and several hairs of a newborn girl. This was a gift to her, the Goddess of mothers. She was to decide the fate of the little Tatar by birth, and Khanty by fate, as the Khanty goddess Kaltashch Anki gave her life on the edge of this cold, frosty earth. That day she started writing every step of the girl in the sacred paper ornament, her whole life, whether it was long or short, rich or poor, happy or unhappy. She could send her disease if the child's mother had unkind thoughts, or send joyful days if the child's mother had bright thoughts.

Like the legends say about Kaltashch anki:

Turam the father allowed her, the beautiful, to be stronger than all the gods.

Turam the father put her, the almighty, above all the gods.

She was given the right – to continue life,

She was given the right – to give life,

She was given the right – to run life,

She was given the right – to resurrect life.

She was commanded by Turam to be stronger and higher than hundreds of Khanty gods in Heaven and on earth. Only the Great Almighty Turam gave her the right to authorize the birth of not only a child on earth, but also all animals, birds and insects. She gives life to men, and she takes it away. Her golden staff has many threads of deer veins, from which the goddess knots out the length of a newborn's life. How long a person lives in the world depends on this knot of life.

„Don't stand. Give me the cross, there's the guard coming. They can see it.“

She wrapped the knife and the cross in a piece of birch bark, and began digging the ground near the birch. At first, she threw wooden chips into the hole, and then put the gifts in the middle.

„Let's dig in. Quick, put the turf so that it's not visible,“ Pukan anki rushed her friend.

Having covered everything with earth and turf, women instantly grabbed shovels to make a dugout. Soon a guard came up and began to question:

„What did the old man want?“

„He said something, but we couldn't understand what he wanted. We thought he would go to the authorities, but he went to his place. Maybe he wanted to bring some fish, we don't know.

Maybe he scolded us that the girl was thrown. We don't understand his language.

„You fools, why did you open your mouths? Be silent about the child, otherwise I will send you further north.“

Women said, stumbling:

„Don't ask us! We did not see the baby“»

What and to whom could they say, bonded people of huge Russia under constant guard? Neither they had homes, nor the land, nor households – and nor rights. Their only goal was to save a man in themselves, not to become a beast in this remote taiga. Even this was hardly possible: every person those days thought only of his life, not of nobility. In order to survive, you needed to become slippery like a smelly burbot, slimy, toothy like a pike. But, as you know, pike and burbot always fall into the largest boiler. It's more convenient to cook large pieces of fish well.

It seemed that people lived on a deserted, god-forgotten land. The only ship on the Ob came once a month from afar. For thirty-forty kilometers from each other, you could find inconspicuous Khanty villages. In the small, dull gorts that were hidden near deep saimes, there were only two or three huts. The father's house – the clan's house, and, perhaps, the houses of older sons separated by age. However, every day at least one boat passed along the Ob banks, then another one sailed upstream. In good weather, light boats quickly disappeared behind the turn of the Ob, and on fishing boats, kayaks, that were stable on the waves, there were several people. Rowers struggled in three oars with the fast flow of the high-water As river, which had spread widely over the litter. It was good if they went down the river, but if they were sailing up, they had to stay close to the shore, where the current slowed down due to the shallow water.

No one was surprised when a few days later authorities approached the village. When people saw the boat arriving, they looked out of the doors and closed them again. There were attentive eyes looking from all the low windows of the huts and houses. District officials walked into the village council with a red flag fluttering. Soon the messenger boy ran to the houses, calling people to the gathering. Levne stepped out of the house with Anshem iki, looking around, and ran into the forest with the cradle. Anshem iki and his granddaughter went to the gathering. A high boss from the district stood next to the chairman, looking at the ignorant people who did not understand anything in the new life. He frowned, carefully examining people. Clearing his throat loudly, the guest spoke menacingly:

«Someone from your village took a newborn from exiled kulaks, from criminals. Who was it?»

The Khanty were silent as always. What could they say without knowing the Russian. Kurtan iki, the assistant chairman of the village council, wanted to get forward, but someone rudely pulled him back. A large man blocked him with his back and said loudly:

«Our babys here. Other baby no walk.»

«Baby no walk,» the newcomer from the district mocked, «so we have the newborn already walking!»

Someone convincingly spoke from the crowd:

«Hoyat baby holt tulev?»

Kurtan iki again began to get out of the crowd. He really wanted to help the authorities: they had important, necessary laws, but his fellow villagers didn't understand that a child of strangers had no place in the Khanty village:

«We have baby!»

«What? Where is the baby?» The visitor exclaimed.

«Turkoi kurt luti toock baby, mun at watsev nyavram!» Kurtan iki was painfully squeezed among the crowd, and went silent.

«That's ok, keep quiet! We'll check every home now. Chairman, take us to all the houses. Look at them! They decided to hide the children of the kulaks. Apples don't fall far from the tree.»

People were silent as they poorly understood Russian, but firmly held Kurtan iki.

The district authorities, along with the gloomy chairman, went with a family check. Anshem iki's neighbor, pushing into the back of the abiding Kurtan iki, headed towards the river. Kurtan iki resisted, but, fearing his cousin, continued to walk with him.

«If you live with bad thoughts, I'll drown you in the Ob,» the broad-shouldered man reprimanded the black-haired relative with cunning eyes. Kurtik iki was completely depressed from the frustration, lowering his shaggy head: he couldn't do a good deed for the authorities.

Kurtan iki was not liked in the village: he was envious, and the luck of his relatives never pleased him. Under the new government, he could compliment, almost bowing to every boss. He could slander anyone before him. He did this, of course, not for the benefit of himself, but for the benefit of the new government. He reported to his relatives, but received no gratitude from the authorities. They did not even thank him, but he already became addicted. Kurtan iki had nothing to do at the honorable work of the Russians, nor he went hunting like his brothers or other relatives. It seemed to him that his work was precisely in this, and it pleased him. What about the villagers? Constantly dissatisfied, illiterate. He didn't know how to write, but could sign documents. He didn't draw tamgu on paper – he wrote his name in letters.

Kurtan iki was the last child in a large family. His mother was fifty years old when she suddenly felt another heart beating under her heart. In their old age, his parents indulged their last child, allowing him whatever he wanted. While elder children helped around the house, went fishing, hunting, harvesting firewood and water, the favorite child played late until night with the neighboring children. The best pieces at the table went to the youngest, and he was used to taking it for granted. If only everything was done for him. Kurtan iki did not learn anything good from hardworking, kind parents.

Having looked at the work of the new authorities, who, without going into the forest for prey, without blood corns from oars, calmly earned money for bread, Kurtan iki was delighted. For Russians, those who have learned one or two letters were no longer illiterate. Therefore, he went to serve them, exposing himself to his superiors in every possible way. Soon he was appointed foreman. The bosses didn't need to catch fish, or get cold at a frozen ice-hole. Now he himself was the head of everything.

But no one envied him, although the new foreman dreamed of it. He envied everyone. His fellow villagers were indifferent to power. And his wife, silent Utiane, was not happy for him. She did not care if he was the boss or just her husband.

Noone knew who was to blame: the NKVD people or someone from the village who was informed about the newborn. The guards of the settlers was free. From time to time they came for fresh meat in the Khanty part of the village. They ate fish together, but someone, apparently, couldn't stop thinking of the baby born. But for some reason no one reported that they took a fresh catch from the population.

Finding nothing in Pitlourkurt, district authorities left for the next village to look for the unknown child. As soon as everything calmed down in the village, Anshem Iki went into the forest for his wife. Soon they returned home. The baby's face was smeared with mud and ash, although the little Tatar was no different from the Khanty children. They did it just in case: who would touch a dirty girl?

The authorities couldn't find the child, so soon they calmed down. How could one find a newborn in large Khanty families? Women gave birth according to ancient customs, in small clean houses specially set for mothers, with a bonfire that cleansed and warmed a woman in labor. You can't give birth in a house, it's a great sin. The child must be clean from all human sins and evil spirits.

There wasn't a single hospital within three hundred kilometers from the village. No Khanty woman in those years would dare to commit a terrible sin and let a doctor take birth. They had a midwife for this – and that was enough. The children were registered in the village council much later after the birth, while others were not taken into account by the Soviet government at all.

After the umbilical cord fell off at the little Tatar, women gathered at Anshem iki's house, bringing the children dressed up for the ceremony of initiation. Levne appointed mother assistants to the newborn girl – Pukan anki, Altam anki, Perna anki, and most importantly, according to the ancient custom, she thanked the goddess Kaltashch, to whom she dedicated her new child. It was she, Kaltashch Anki, who gave children to a family. Levne prayed to her, bowing her head in gratitude for the happiness of a fair-haired Tatar girl accidentally falling on her head:

«Long-braided, Golden Nye!

More beautiful than the sun, Golden Nye!

More beautiful than the beautiful, Golden Nye!

In a silk shawl colored like the morning dawn, whose long tassels are decorated with uncountable silver stars.

In the sable clothes, white kisas embroidered with the sacred ornament, sitting in your golden house in Heaven, goddess Kaltashch, you sent us a blessed day,» prayed Levne.

«My soul sings with happiness, and I thank you for the priceless gift, for the fair-haired daughter, who smiles with her ember eyes. I dedicate her soul to you. Take care of her, let her please us with her bright smile!» Grateful Levne bowed three times to the goddess.

«Your long braids are falling, Heavenly Nye, with a seven-fold silk sable from the mouth of the deep-water Ob to the Kara Sea itself. At night, under the moonlight and a thousand stars, your hair illuminates everything around. Even for our daughter moonlight and stars illuminate your face. On a clear day, your braids illuminate summer land covered with a green carpet, winter land with a white snow coat. Let the ends of your golden braids touch the head of our baby. Each of your fingers is wearing countless gold and silver, expensive and cheap rings – gifts of all the women of the Khanty land that gave birth or wish to have children. Take the ring from me too!»

At the sacred labaz, Levne laid a scarf with a silver ring tied in a corner and several hairs of a newborn girl. This was a gift to her, the Goddess of mothers. She was to decide the fate of the little Tatar by birth, and Khanty by fate, as the Khanty goddess Kaltashch Anki gave her life on the edge of this cold, frosty earth. That day she started writing every step of the girl in the sacred paper ornament, her whole life, whether it was long or short, rich or poor, happy or unhappy. She could send her disease if the child's mother had unkind thoughts, or send joyful days if the child's mother had bright thoughts.

Like the legends say about Kaltashch anki:

Turam the father allowed her, the beautiful, to be stronger than all the gods.

Turam the father put her, the almighty, above all the gods.

She was given the right – to continue life,

She was given the right – to give life,

She was given the right – to run life,

She was given the right – to resurrect life.

She was commanded by Turam to be stronger and higher than hundreds of Khanty gods in Heaven and on earth. Only the Great Almighty Turam gave her the right to authorize the birth of not only a child on earth, but also all animals, birds and insects. She gives life to men, and she takes it away. Her golden staff has many threads of deer veins, from which the goddess knots out the length of a newborn's life. How long a person lives in the world depends on this knot of life.