По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

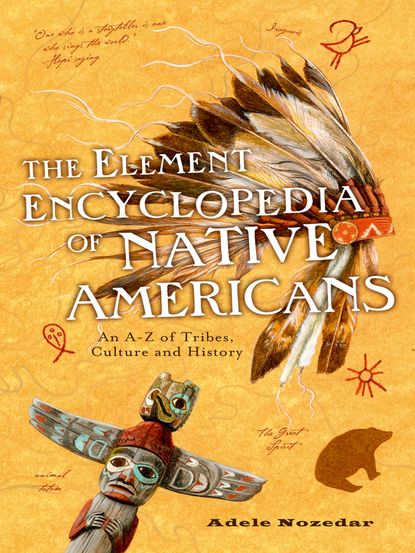

The Element Encyclopedia of Native Americans: An A to Z of Tribes, Culture, and History

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

It was suggested to the Native Americans that one of the reasons the white man had been able to dominate was that the Natives were not educated. If their children were brought up in the European way of education, and taught to read and write English, they would be better off for it. Accordingly, many Native families sent their children to the Carlisle School voluntarily. Subsequently, as 26 more schools sprang up using the example of the Carlisle School as their inspiration, the Bureau of Indian Affairs applied more pressure in separating children from their families.

At the Carlisle School, it was initially forbidden to use any language other than English, and when they first arrived children were given new English names. Also, a young student arriving at the Carlisle School would be given an enforced haircut. Many tribes believed that cutting the hair was a sign of mourning, and consequently the children would often weep until late into the night after this treatment. Their own clothes were taken away and replaced with formal Victorian dresses for the girls and military uniforms for the boys. There are archives of “before and after” photographs, ordered to be taken by Pratt, which were sent to Washington to show the difference in the children’s appearance to prove that all was in order.

For a student of the Carlisle School, the day’s regime was strict: the pupils were even expected to march, military-style, to their classes. The mornings were spent in academic studies (subjects included English, history, and math) and the afternoons were spent in learning skills that might be useful in adult life, such as woodwork and blacksmithing for the boys, laundering and baking for the girls. Children were inevitably schooled in the Christian faith. The rigid discipline of the Carlisle School also extended to its methods of punishment. Hard labor and confinement were usual for transgressors of the strict school rules. Children were even locked into the small cells of the former military guardhouse on the premises, sometimes for up to a week.

There were many critics of the Carlisle method of teaching, among them a former female pupil, Zitkala-Sa.

Many pupils struggled at the school—as well as the shock of separation from everything they held dear, including their parents, many died after contact with European diseases. Some 192 children, primarily from the Apache tribe, died and were buried at the school site.

One of the more successful programs of the Carlisle School was a scheme, invented by Pratt, called the Outing System. Students were sent to live with white families to observe their way of life and live within their society. After this experience students were able to train in various jobs, which eventually led to “legitimate” employment.

After Pratt retired in 1904, some of the stricter practices of the school were relaxed a little, and the emphasis shifted from the military and academic to sports and athletics. One pupil, Jim Thorpe, a Sauk whose original name was Bright Path, was a particularly brilliant sportsman, described at the time as the world’s greatest athlete. He went on to compete in the decathlon and pentathlon events at the 1912 Olympics, winning two gold medals.

The school eventually closed its doors in 1918.

CARSON, KIT

1809–1868

Born in Kentucky and christened Christopher Houston Carson, Kit Carson was one of 15 children, and moved as an infant with his family to Missouri. Carson would have a colorful career, including an apprenticeship to a saddle maker at the age of 15, as part of a group of itinerant merchants headed toward Santa Fe, for whom he tended the horses, as a trapper, an explorer and guide, as an Indian agent, and as an officer in the U.S. Army, promoted to the position of General shortly before his death.

The name of Kit Carson has become legendary, used in fictionalized accounts of the Wild West in books, movies, and in several TV series.

CASINOS

Reservations are governed by the Native American people who own them. So long as the state in which a reservation is situated allows gaming and gambling, then the reservation is permitted to open casinos if the owners so wish. The Reagan administration (1981–1989) placed an emphasis on the tribes becoming self-sufficient, and so those living on the reservations were keen to find new ways to try and lift the people out of the extreme poverty that affected many.

The very first tribe to open a gambling operation were the Seminole in Florida. They opened an elite bingo operation, with valuable prizes. The state tried to close down the venture, but the courts ruled in favor of it. In the early 1980s, another court case established the right for reservations to run gaming and gambling operations—this landmark case was “California vs. Cabazon Band of Mission Indians.” In 1988, reservation gambling and gaming laws were further supported by the Indian Gaming Regulatory Act. Casinos on reservations now draw significant crowds, and bring in a healthy revenue, especially since the casinos themselves often include conference facilities, hotels, and other tourist attractions.

CASSAVA

Also called manioc, this was an important food source, particularly for the Arawak.

CATAWBA

Also known as the Esaw or Issa, which name refers to the river running through their ancestral lands, the Catawba were at one time considered to be the most important tribe in the Carolinas. About 250 years ago there were estimated to be 5,000 tribal members in North and South Carolina. The tribe belong to the Siouxan language family.

Despite constant battles and skirmishes with other tribes in the area—including the Cherokee, the Delaware, and the Shawnee—the Catawba were, on the whole, well-disposed toward the very early European explorers and settlers. However, like many other tribes, the Catawba fell prey to the white man’s diseases—in particular, smallpox: in 1759 a severe epidemic obliterated almost half of the tribe, who had no immunity to the illness.

In 1763 the tribe were allocated a reservation of approximately 15 square miles which straddled both sides of the Catawba River. Fighting on behalf of the Americans against the British in the War of Independence, the tribe relocated to Virginia at the approach of the British troops, but returned afterwards and formed two villages on the reservation. In the early 19th century the tribe chose to lease their land to white settlers, and in 1840 they sold the entire reservation, all except for one square mile, and headed toward Cherokee country, where they found that the relationship with their old adversaries was as bad as it ever had been. Although there were instances of intermarriage between the two tribes, for the most part the Catawba returned to South Carolina.

The Catawba were an agricultural tribe and, in common with other Indian peoples who enjoyed a stable existence, were able to devote time to experimenting with basketware and pottery. Hunting and fishing supported their farming endeavors.

In terms of religion, the Catawba believed in a trinity of the Manitou (or creator), the Kaia (or turtle), and the Son of the Manitou. It’s possible that this idea of a trinity was influenced by the beliefs of the Christian faith of the white settlers. When the Mormons visited the tribe in the 1880s, several members of the Catawba converted, and some even relocated to Utah.

CATLIN, GEORGE

“I have, for many years past, contemplated the noble races of red men who are now spread over these trackless forests and boundless prairies, melting away at the approach of civilization.”

1796–1872

Arguably the most famous painter of the Native American, Catlin’s writings as well as his paintings provide a rich heritage of information about the indigenous peoples of America, invaluable in that Catlin lived closely among them, studying their customs and habits, languages, and ways of living.

Born in Pennsylvania, although he was trained as a lawyer Catlin opted out of the legal profession quite early on in favor of art, and set up a portrait studio in New York. In common with others, Catlin rightly suspected that the Native American and his way of life were endangered, and so he decided to dedicate his life to the study of the people.

He published two significant volumes of Manners, Customs and Conditions of the North American Indians, replete with 300 engravings, in 1841. In 1844 another book followed: The North American Portfolio contained 25 color plates, reproductions of his paintings. These books are still in print today.

Catlin’s mother inspired his continuing fascination with the Native people of his country. When he was a child she regaled him with stories of how she’d been captured by a band of Indians as a little girl, which no doubt stimulated his childish imagination. Catlin’s appetite for recording the lives of the Native Americans, a passion which led to his giving up a “proper” career, was further excited when he witnessed a delegation of Native Americans passing through Philadelphia.

In 1830 he joined General William Clark on his expedition up the Missouri. Basing himself in St. Louis, Catlin managed to visit at least 50 different tribes, and later traveled to the North Dakota—Montana border, where the tribes—including the Mandan, Pawnee, Cheyenne, and Blackfeet—remained relatively untouched by the encroaching Europeans. When he returned home in 1838, he assembled his works—which included some 500 paintings of Native Americans and their way of life—into his “Indian Gallery.” He also included artifacts in the exhibition.

Catlin lectured extensively about his experience, and in 1839 took the Indian Gallery exhibition on tour of the major European capitals—Paris, London, and Brussels. However, none of this generated an income and Catlin was forced to seek a buyer for his work. He was desperate to keep his life’s work intact, and spent some time trying to convince the U.S. Government to purchase the entire collection, but in vain. Eventually, he sold the entire collection of 607 paintings to a wealthy industrialist, Joseph Harrison, who put it into safe storage. In 1879, after he died, Joseph Harrison’s widow donated the Indian Collection, a deal of which had suffered the ravages of time and were mouse-eaten and damp, to the Smithsonian Institution, where Catlin had worked for a year just before his death. It remains a part of the Institution’s collection.

CAT’S CRADLE

The traditional game played by two or more children, who “weave” a loop of string in and out of each other’s hands. Traditionally played by the Navajo and Zuni peoples.

CAYUGA

One of the five original tribes of the mighty Iroquois Confederacy (Haudenosaunee), the name Cayuga means “People of the Great Swamp” or else “People of the Mucky Land.”

During the Revolutionary War, the Cayuga had fought on both the British and the American sides; however, the majority of the Iroquois elected to support the British in the hopes that a British victory would put an end to encroachment by the settlers onto Native territories. The power of the Iroquois posed a real threat to the plans of the Americans, and in 1779 the future president, George Washington, devised a military campaign specifically aimed at the Confederacy. Over 6,000 troops destroyed the Cayuga’s ancestral homelands, razing some 50 villages to the ground, burning crops so that the people would starve, and driving the survivors off the land. Many of the Cayuga, along with other tribes, fled to Canada where they found sanctuary and were given land by the British in recognition of their aid. Although the Seneca, the Iroquois, the Oneida, and the Onondaga tribes of the Confederacy were given reservations, the Cayuga were not. Earlier, however, small bands of Seneca and Cayuga had relocated to Ohio, and many other Cayuga joined them because they had no home. The Cayuga—along with the rest of the Haudenosaunee—signed the Treaty of Canandaigua in 1794, which ceded lands to the new United States Government. Thereafter, the floodgates opened for the former Cayuga lands, and settlers arrived there in droves.

CAYUSE

Of the Penutian language group, the original meaning of the word Cayuse has been lost in the mists of time. However, because of the tribe’s particular skill in breeding horses and also in dealing them, their name has become synonymous with that of a particular small pony that they bred. The Native American name of the Cayuse is Waiilatpu. Associated with the Nez Perce and Walla Walla, the Cayuse lived along the Columbia River and its tributaries from the Blue Mountains as far as the Deschutes River in southeast Washington and northeast Oregon.

The Cayuse lived in a combination of circular tentlike structures and rectangular lodges. Extended families made small bands, each with its own headman or chief. The horses that became such an important part of the life of the tribe were introduced to them in the early part of the 18th century. Trading was not restricted to horses, though; the Cayuse bartered with the coastal tribes items such as buffalo blankets for shells. Later, they would trade with the white men: furs for guns and tools.

The Cayuse War of 1847–1850 was ignited by an outbreak of one of the European diseases for which the Native American tribes had no immunity: measles. The disease was first contracted by the Cayuse children who attended the mission school, and it spread to the adults.

The people who had started the mission school were not popular, and it seems that they had made little attempt to establish good and meaningful relationships with the Cayuse, with whom they had lived and worked for ten years. Marcus Whitman and his wife, Narcissa, were Presbyterians and had started the Waiilatpu Mission in 1836. The couple took little notice of the traditional ways and customs of the Cayuse and were zealous in their pursuit of converts. Moreover, it was rumored that they had made money for themselves from resources which should have belonged to the Cayuse: furs and land sales.

At the outbreak of measles, then, a chief and another Cayuse visited the mission in search of medicine, already angry with Whitman since, as well as any other grudges they had against him, they blamed the mission for the disease. Whitman was attacked and killed. Shortly afterward, the angry Cayuse attacked again, killing Narcissa along with ten other white people.

An army was organized by Oregon County officials, who retaliated by raiding a Cayuse settlement and killing some 30 people. The Natives in the area, including the Walla Walla and the Palouse, allied with the Cayuse against the Oregon army. Cornelius Gilliam, the army leader, was shot by his own gun and his troops fled. In the meantime, the two Cayuse who had visited the mission for the medicine, Tomahas and Tilokaikt, had fled immediately after the incident. Tired of hiding, after two years they gave themselves in, hoping for mercy. But they were sentenced to death by hanging.

The Cayuse uprising caused change in Oregon, with new forts and military posts being built; this in turn exacerbated mistrust between the Natives and the white people, which led to more wars. In time, the Cayuse were forced onto a reservation in 1853, in northeastern Oregon and southeastern Washington. Whitman was honored by having a town named after him in Washington.

CELT

A tool used as a scraper (for scraping hides, for example), as an ax for chopping meat, as a skinning knife, for woodworking, and also as a weapon of war, a Celt was made from hard stone, shaped in the form of a hatchet but without a handle.

CHANUNPA

This is the Sioux name for the ceremonial smoking pipe, and also the ceremony that features it. An ancient legend has it that the chanunpa was brought to the people by the White Buffalo Calf Woman, in order that it might enable the tribes to communicate with the sacred and divine worlds of The Great Mystery, or Wakan Tanka.

CHEROKEE