По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

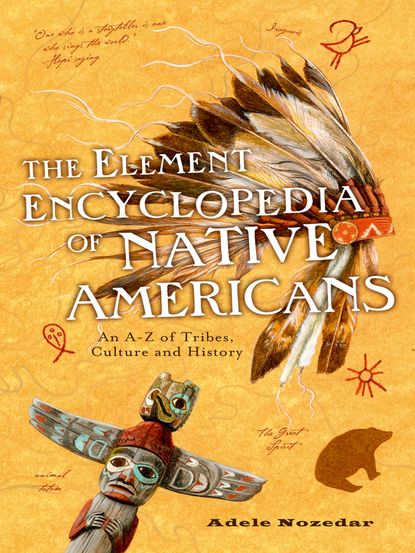

The Element Encyclopedia of Native Americans: An A to Z of Tribes, Culture, and History

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

That we know so much about the life of Black Elk is because of a man named John Neihardt. As an historian and ethnographer, Neihardt was, in the interests of his personal research, searching out Native Americans who had a perspective on the Ghost Dance Movement. He was introduced to Black Elk in 1930, and thus began a productive collaboration which would provide a major contribution to the Western perspective on Native American life and spirituality—coming, as it did, from an authority on such subjects. The books they produced, including Black Elk Speaks, became classics, and are still in print today.

Living during the time that he did, Black Elk was in a unique position: born into the Oglala Lakota division of the Sioux, he not only participated in the Battle of Little Big Horn in 1876, when he would have been 12 or 13, but also toured as part of Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show in the 1880s, and traveled to England when the show was performed for Queen Victoria in 1887. He was 27 when the massacre at Wounded Knee took place in 1890, during which he sustained an injury.

Black Elk was a heyoka, a medicine man, and a distant cousin to Crazy Horse. Elk was born in Wyoming in 1863. Acknowledged as a spiritual leader and as a visionary, Black Elk’s first revelation came to him when he was just nine years old, although he did not speak of it until he was older. In this vision, he said, he met the Great Spirit and was shown the symbol of a tree, which represented the Earth and the Native American people.

After Wounded Knee, Black Elk returned to the Pine Ridge Reservation and converted to Christianity. He married Katie War Bonnet in 1892. All three of their children, as well as their mother, embraced the Catholic faith, and in 1903, after Katie died, Black Elk, too, was baptized, although he remained the spiritual leader among his own people. He saw no inherent problems in worshipping both the Christian God and Wakan Tanka, or the Great Spirit—an open-minded attitude which undoubtedly was not shared by his fellow Catholic. Black Elk married once more in 1905, and he and Anna Brings White had three more children. He was one of the few surviving Sioux to have first-hand knowledge of the rituals and customs of the tribe, and he revealed some of these secrets to both Neihardt and Joseph Epes Brown, who published books based on his knowledge.

BLACK HAWK (MAKATAIMESHEKIAKIAK)

“Courage is not afraid to weep, and she is not afraid to pray, even when she is not sure who she is praying to.”

1767–1838

In what is now called Rock Island, Illinois, there was once a village called Saukenuk, and this is where Black Hawk, also known as Black Sparrow Hawk, was born. His father, Pyesa, was the medicine man of the tribe, and, in accordance with his destiny to follow in his father’s footsteps, Black Hawk inherited Pyesa’s medicine bag after Pyesa was killed in a battle with some Cherokee.

Like many other young men of his people, Black Hawk trained in the arts of battle from an early age. When he was 15, he took his first scalp after a raid on the Osage tribe. Four years later he would lead another raid on the Osage, and kill six people, including a woman. This was typical of the training in warfare given to young Native Americans.

After the death of his father Pyesa, Black Hawk mourned for a period of about six years, during which time he also trained himself to take on the mantle of his father, as medicine man of his people. It would also prove a part of his destiny to lead his people as their chief, too, although he didn’t actually belong to a clan that traditionally gave the Sauk their chiefs. It was Black Hawk’s instinctive skill at warcraft that accorded him the status of chief; this sort of leader by default was generally named a “war chief” since, sometimes, circumstances dictate the mettle of the leader that was needed.

When he was 45, Black Hawk fought in the 1812 war on the side of the British under the leadership of Tecumseh. This was an alliance that split the closely aligned Sauk and Fox tribes. The Fox leader, Keokuk, elected to side with the Americans. The war pitted the North American colonies situated in Canada against the U.S. Army. Britain’s Native American allies were an important part of the war effort, and a fur-trader-turned-colonel, Robert Dickson, had pulled together a decent sized army of Natives to assist in the efforts. He also asked Black Hawk, along with his 200 warriors, to be his ally. When Black Hawk agreed, he was given leadership of all the Natives, and also a silk flag, a medal, and a certificate. He was also “promoted” to the rank of Brigadier General.

After this war, Black Hawk led a group of Sauk and Fox warriors against the incursions of the European-American settlers in Illinois, in a war that was named after him: the Black Hawk War of 1832. It was this Black Hawk War that gave Abraham Lincoln his one experience of soldiering, too.

Black Hawk was vehemently opposed to the ceding of Native American territory to white settlers, and he was angered in particular by the Treaty of St. Louis, which handed over the Sauk lands, including his home village of Saukenuk, to the United States.

As a result of this treaty, the Sauk and Fox had been obliged to leave their homelands in Illinois and move west of the Mississippi in 1828. Black Hawk argued that when the treaty had been drawn up, it had been done so without the full consultation of the relevant tribes, so therefore the document was not, in fact, legal. In his determined attempts to wrest back the land, Black Hawk fought directly with the U.S. Army in a series of skirmishes across the Mississippi River, but returned every time with no fatalities. Black Hawk was promised an alliance with other tribes, and with the British, if he moved to back to Illinois. So he relocated some 1,500 people—of whom about a third were warriors and the rest old men, women, and children—only to find that there was no alliance in existence. Black Hawk tried to get back to Iowa, and in 1832 led the families back across the Mississippi. He was disappointed by the lack of help from any neighboring tribes, and was on the verge of trying to negotiate a truce when these attempts precipitated the Black Hawk War, an embittered series of battles that drew in many other bands of dissatisfied Natives for a four- to five-month period between April and August of 1832. At the beginning of August the Indians were defeated and Black Hawk taken prisoner along with other leaders including White Cloud. They were interred at Jefferson Barracks, just south of St. Louis, Missouri. By the time President Andrew Jackson ordered the prisoners to be taken east some eight months after their internment, their final destination to be another prison, Fortress Monroe, in Virginia, Black Hawk had become a celebrity; the entire party attracted large crowds along the route and, once in prison, were painted by various artists. Toward the end of his captivity in 1833, Black Hawk dictated his autobiography, which became the first such book written by a Native American leader. It is still in print today, a classic, and is a timeless testament to Black Hawk’s dignity, honor, and integrity.

After his release, Black Hawk settled with his people on the Iowa River and sought to reconcile the differences between the other tribes and the white men. He died in 1838 after a brief illness.

BLACK HAWK WAR

SeeBlack Hawk (#u41fbc57c-5c3d-495f-b796-87bea9d8a9fb)

BLACK KETTLE

“Although wrongs have been done to me, I live in hopes. I have not got two hearts … Now we are together again to make peace. My shame is as big as the earth, although I will do what my friends have advised me to do. I once thought that I was the only man that persevered to be the friend of the white man, but since they have come and cleaned out our lodges, horses and everything else, it is hard for me to believe the white men anymore.”

1803(?)–1868

Born as Moketavato in the hills of South Dakota, Black Kettle was a Cheyenne leader who, in 1854, was made chief of the council that formed the central government of the tribe.

The First Fort Laramie Treaty, dated 1851, meant that the Cheyenne were able to enjoy a peaceable existence, However, the Gold Rush which started a few years later in 1859 meant that the hereditary tribal lands were encroached upon by gold-hungry prospectors who invaded Colorado. The Government, whose duty it should have been to uphold the treaty, instead tried to solve the problem by demanding that the southern Cheyenne simply sign over their gold-rich lands, all except for a small reservation, Sand Creek, which was located in southeastern Colorado.

Black Kettle was pragmatic, and also concerned that unless they agreed with what the U.S. Government was suggesting, a less favorable situation might be on the horizon. Accordingly, the tribe moved to Sand Creek. Sadly, the land there was barren; the buffalo herds were at least 200 miles away, and in addition to these hardships a wave of European diseases hit the tribes and left their population severely weakened. The Cheyenne had no choice but to escape the reservation, relying on thieving from passing wagon trains and the white settlers. These settlers took the law into their own hands and started a volunteer “army”; the fighting escalated into the Colorado War, 1864–1865. The Sand Creek Massacre, a result of this war, saw 150 Natives slaughtered, many of them either the very old or the very young. Despite his wife having been severely injured at Sand Creek, Black Kettle continued to arbitrate for peace, and by 1865 had negotiated a new treaty which replaced the unusable Sand Creek Reservation for lands in southwestern Kansas.

Many of the Cheyenne refused to join Black Kettle in the exodus to Kansas, choosing instead to join up with the northern band of Cheyenne in the hills of Dakota. Others aligned themselves with the Cheyenne leader Roman Nose, whose approach to the white settlers was diametrically opposed to that of Black Kettle. Roman Nose believed the way forward was not via treaties or agreements, but via brute force. The U.S. Government saw that the Cheyenne were simply ignoring the new treaty, and sent General William Tecumseh Sherman to force them onto the assigned reservation.

Roman Nose and his followers retaliated by repeated attacks on the white settlers who were heading westbound; these attacks were so prevalent that passage across Kansas became virtually impossible. The Government tried to relocate the troublesome Cheyenne once again, this time to the Indian Territory in Oklahoma, tempted by promises of food and supplies.

Once again, the peacemaker Black Kettle signed the agreement, which was entitled the Medicine Lodge Treaty of 1867. However, the promises were empty; even more of the Cheyenne joined Roman Nose’s band and continued to stage attacks on the farms and dwellings of the pioneers. General Philip Sheridan devised an attack on the Cheyenne habitations. George Armstrong Custer was the leader in one of the attacks which was launched on a Cheyenne village on the Washita River. This was Black Kettle’s village. Despite the fact that the village was within the reservation, Custer launched an attack at dawn. He also ignored the fact that the white flag was flying from Black Kettle’s tipi. In 1868, 170 peaceful Cheyenne were massacred. Among the dead were Black Kettle and his wife.

BLACKFEET SIOUX

Nothing to do with the Blackfoot Tribe, the Blackfeet Sioux, also referred to as the Siksika or Pikuni, originally lived by the Saskatchewan River in Canada and in the very northernmost parts of the United States. By the middle of the 19th century, however, they had relocated to the Missouri River and the Rocky Mountains, close to the Standing Rock Agency and Reservation. The tribe are part of the Algonquian language family.

A band of the Dakota Sioux, there are two legends that explain how the name of the Blackfeet Sioux came about.

The first explains that some of the tribe had been chasing some Crow Indians; however, the quest was dramatically unsuccessful and resulted in the Sioux braves losing everything, including their horses. They were forced to return home on foot, across scorched ground, hence when they got back their moccasins were stained black.

The second myth describes how a certain chief, jealous of his wife and wanting to keep tabs on her, blackened the soles of her moccasins so he could track her wherever she went.

From 1837 to 1870 the tribe’s population was drastically reduced during a series of smallpox epidemics. In common with other Native Americans, the Blackfeet had no natural immunity to the disease. We know that somewhere in the region of 6,000 Blackfeet people died in the 1837 outbreak alone. In 1888 the tribe were forced by the U.S. Government to relocate once more, to the Blackfeet Reservation in Montana.

BLACKFOOT CONFEDERACY

Also called the Siksika, meaning “Blackfoot,” or the Niitsitapi, meaning “original people.” Blackfoot/Niitsitapi is the name of a confederacy of tribes: the North Piegan, the South Piegan, the Siksika, and the Kainai. All these tribes belonged to the Algonquian language family. The entire group were large and renowned for their ferocity in battle, second only to the Dakota in size and importance. The Confederacy also gave protection to two smaller bands, the Sarsi and the Atsina, or Gros Ventre. Like the Blackfeet Sioux—a completely different tribe—the Blackfoot, legendarily, were meant to have been given their name after their moccasins were stained black from prairie fires. These moccasins—which had a beadwork design featuring three prongs—made the Blackfoot immediately recognizable.

The Blackfoot ranged over a large territory, from the North Saskatchewan River in what is now Canada to the Yellowstone River in Montana, and from the Rockies to the Alberta—Saskatchewan border. Having adopted the horse from other Plains tribes, they roamed after the buffalo and lived in tipis in settlements of up to 250 people in up to 30 lodges. Each small band had its leader, and relationships between bands were flexible enough for members to come and go between bands as they pleased. In the summer the bands gathered together; they were among those who performed the Sun Dance ritual. In addition, the Blackfoot had another spectacular ritual: the Horse Dance ceremony.

The natural enemies of the Blackfoot included the Crow, Sioux, Shoshone, and Nez Perce; their most particular enemy, though, came in the form of an alliance of tribes who came under the name of the Iron Confederacy. They would travel long distances to take part in raids on other tribes. A young Blackfoot boy on his first such raid was given a derogatory name until he had killed an enemy or stolen a horse, when he was given a name that carried honor with it. Like other Native Americans, a lack of immunity to the most common European diseases had brought tragedy to the Blackfoot for many years; in one of the worst incidents, in 1837, some 6,000 Blackfoot perished when smallpox was contracted from European passengers on a steamboat.

During the protracted winter months, the camps of Blackfoot hunkered down, perhaps camping together when stores were adequate. The buffalo were easier to hunt during the winter, simple to track through the snow. Hunting took place when other resources were beginning to run low. For the Blackfoot as well as other Native American peoples, the buffalo was an essential part of their lifestyle. However, deliberate overhunting by the Europeans in an attempt to weaken the Natives by taking away their primary resource meant that, from the 1880s onward, the Blackfoot had to adopt new ways of survival. The Canadian members of the Confederacy were appointed reservations in southern Alberta in the late 1870s, which saw them struggle as they faced many hardships connected with a completely new way of life after generations of roaming freely. The Blackfoot were forced to turn to the white man for help, relying on the U.S. Government for food supplies, which were very often not forthcoming or rotten and inedible. The tribe were forced to turn to theft, which resulted in counterattacks from the Army; these attacks often saw women and children killed.

The worst winter, 1883–1884, “Starvation Winter,” was so-called because not only were there no buffalo, but no supplies from the Government. Approximately 600 Blackfoot perished.

BLAZING A TRAIL

We use the term “blazing a trail” to describe a pioneering endeavor of any kind, but its origins are altogether more pragmatic.

To blaze a trail was a way for either a Native or a white man to mark a route, often surreptitiously, so that the trail would be followed only by someone who was familiar with the signs that were left along it. Methods used to show direction might include sticks laid on the ground in a certain way, notches taken from trees or shrubs, or an arrangement of stones, rocks, or leaves on the ground.

BLUE JACKET

1740(?)–1810

Also known to his own tribe as Weyapiersenwah, Blue Jacket was a war chief of the Shawnee people. We don’t have a great deal of information on his early life; he first comes into focus in 1773 when he would have been in his early thirties. He is first mentioned in the records of a British missionary who had visited Shawnee settlements, and mentioned Blue Jacket as living in what is now Ohio.

There’s a strange legend surrounding Blue Jacket: that he was, in fact, Marmaduke Swearingen, a European settler who had been kidnapped, and subsequently adopted by, the Shawnee. So far, though, no definitive information has proved this legend; rather, records describe Swearingen and his entire family as being fair-skinned with blond hair. If this description had been applied to Blue Jacket, there is no doubt that there would be some mention of it somewhere.

Blue Jacket was among the many Natives who fought to retain their land and their rights. During the American Revolutionary War, many Indians supported the British, believing that a British victory would end the encroachment of the settlers. When the British were defeated, the Shawnee had to defend their territory in Ohio on their own, a task they found increasingly difficult in the face of a further escalation of European settlers. Blue Jacket was a very active leader in his people’s resistance.

The pinnacle of Blue Jacket’s career as a war chief was when he led an alliance of tribes, alongside the chief of the Miami people, Blue Turtle, against the U.S. Army expedition led by Arthur St. Clair. The Battle of Wabash proved to be the most conclusive defeat of the U.S. Army by the Natives.

However, the American Army could not let this Indian victory go unchallenged, and raised a superior group of soldiers; in 1794 they defeated Blue Jacket’s army at the Battle of Fallen Timbers; the result was the Treaty of Greenville, in which the United States gained most of the former Indian lands in Ohio. A further treaty signed by Blue Jacket was the Treaty of Fort Industry, in which even more of the Ohio lands were taken by the U.S. Government.

Blue Jacket died in 1810, but not before he witnessed a new person take on his role as chief. Tecumseh carried on Blue Jacket’s fight to win back the Indian heritage in Ohio.

BOLA