По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

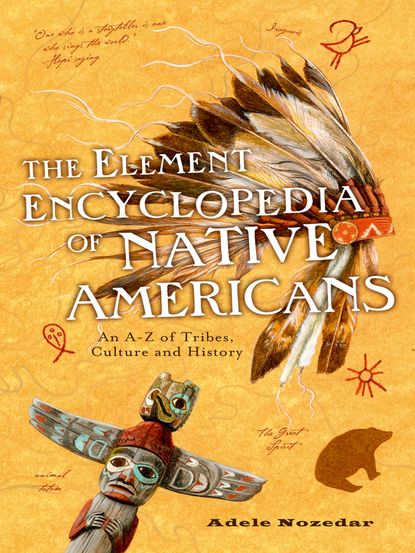

The Element Encyclopedia of Native Americans: An A to Z of Tribes, Culture, and History

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

AMOS BAD HEART BULL

1868-1913

Also known as Eagle Bonnet, Amos Bad Heart Bull belonged to the Oglala Lakota branch of the Sioux Nation. The nephew of the chiefs He Dog and Red Cloud, and the son of Bad Heart Bull and his wife, Red Blanket, Amos grew up in the traditional way for a young Lakota boy, although his upbringing was disturbed by the growing unrest between the tribe and the European settlers. Amos was only eight years old when the Sioux defeated General Custer at the Battle of Little Big Horn; despite their victory, the Great Sioux War saw the tribe eventually overcome, and Amos’ family fled north to be with the great chief, Sitting Bull, in Canada, for a few years before returning south to the Standing Rock Reservation, and then to the Pine Ridge Reservation, in the early 1880s.

Amos was interested in the history of his people and this, combined with an artistic skill, saw him start to draw pictures showing key events in the life of the tribe. His father Bad Heart Bull was responsible for keeping the Winter Count, a pictorial calendar, and it’s likely that the young Amos picked up these skills from his father.

It was during his time serving as a scout for the U.S. Army that Amos bought a ledger book—intended for accounts, etc.—from a store, and began to draw in it. By chance, he adapted a traditional Indian technique of drawing on hide or skins to a modern medium: paper. This style became known as Ledger Art, and Amos became famous for it. Once he returned to the tribe after his time in the Army, he became the Winter Keeper of the tribe, following in the footsteps of his father before him.

It wasn’t until after his death, though, that Amos’ art gained recognition. His sister, Dolly Pretty Cloud, had inherited the ledger book full of drawings, and she was contacted by a university student, Helen Blish, who wanted to study the drawings as part of her thesis. Her professor, Hartley Alexander, made photographs of the drawings to accompany his student’s text—which was fortunate, since when Dolly died the ledger book was buried with her. The text and drawings were subsequently published in 1938 by Professor Alexander as Sioux Indian Painting. Some 30 years later it was printed again, the content considered a very important record of the history and culture of the Lakota people, this time under the title A Photographic History of the Oglala Sioux, by Helen Blish’s alma mater, the University of Nebraska Press.

ANASAZI

Meaning “The Ancient Ones,” the Anasazi were among the first dwellers in the vast land that became the United States. Sometimes called the “Ancient Pueblo Peoples,” the Anasazi lived in the southwest. The Anasazi have been traced back as far as 6000 B.C., a hunter-gatherer people who had started to settle into agriculture (primarily growing maize as a crop) in the last two centuries B.C. The Anasazi also left behind a significant accumulation of archeological remains that have helped us to understand something of their culture and way of life.

By A.D. 1200, horticulture had become a very important part of Anasazi economy, although prior to this they had still traveled in search of hunting grounds and sources of food. The more settled they became, however, the more skilled the Anasazi became at basket making, and indeed this was so important that the three delineated periods of Anasazi culture, from 1000 B.C. until A.D. 750, are defined as “the three Basket-Making periods.” Remains of these baskets—and sandals—prove that they were not simply utilitarian objects, but works of art, too.

The Anasazi buried their dead in deep circular pits lined with stones, grasses, and mud; they stored goods in the same way. Houses were similar to hogans—circular permanent structures constructed of a framework of branches covered in reeds, grasses, and earth.

By A.D. 500, the Anasazi were settled into a farming culture, living in small settlements that were scattered widely over what is now southern Utah. These settlements could be as small as just three homes, or as large as a “village” containing more than a dozen buildings.

Archeological investigations of Anasazi remains have also helped us to gauge the arrival of the bow and arrow into this part of America. Sometime before A.D. 750, the bow and arrow replaced the older spear thrower. Around about the same time period, the people also started to make pots, probably as a direct result of using a basket lined with clay as a cooking receptacle. It wouldn’t have taken long to realize that the basket itself wasn’t a necessary part of the structure once the clay had hardened (probably in the cooking process). Anasazi pottery came in two grades: the plain “everyday” kind, and the more decorative ware which was patterned with black-on-white designs.

From A.D. 750 onward, we start to think of the Anasazi as the Pueblo. This name refers to the way the people came to live, in solid, stonebuilt multistoried houses. “Pueblo” is not a tribal name, as some suppose.

For 250 years onward, from A.D. 900, the Pueblo houses, formerly made from wooden poles and adobe, started to be replaced with stone masonry, and a floor was developed that was at the same level as the ground. The actual pithouses, or kiva, were used instead for ceremonies.

ANGAGOK

The shaman or medicine man of the Inuit.

APACHE

A tribe from the Northwest, the Apache were renowned for their fearlessness which, combined with a natural ferocity, meant that they were much feared, not only among the white settlers, but by other Natives, against whom were long-running feuds. Since they had been living in New Mexico when the Spaniards had first arrived there with horses, the Apache were one of the first tribes to train, breed, and ride horses after they had captured the animals in raids. It was their horseback raids on the Pueblo settlements of that area that gave them their name: Apachu means “enemy” in the Zuni language, and “fighting men” in the Yuma tongue. Inde, meaning “people,” is the term that the Apachean groups used to refer to themselves. Although the Apache and the Navajo are related, the term “Apache” isn’t used in reference to the Navajo. Both Apache and Navajo are a part of the Athabascan language group.

There were several different bands of tribes that are grouped under the general heading of Apache. These include the Chiricahua, who had the reputation of being the most ferocious of all the Apache groups, the Kiowa Apache (or Plains Apache), the Jicarilla (who cultivated corn as well as hunting buffalo), and the Mescalero (so-named because of their fondness for the roasted heads of the wild mescal plant). The Lipan Apache in Texas were known to be particularly “unruly.” These separate Apache groups didn’t really work in any kind of unity; there were seven different languages between the major groups, as well as diverse cultural differences between those groups.

The Apache were seasonal hunters, ranging after buffalo, deer, and elk. The Apache were matrilinear—that is, the children were deemed to belong to the tribe of their mother and, once married, their father’s obligations lay with their mother’s clan. Although all the separate Apache clans operated distinctly from one another, during times of warfare they banded together to make a formidable fighting force.

As soon as they gained access to firearms as well as horses, the Apache became even more dangerous than before. It’s fair to say that they posed the greatest threat to the Europeans in the desert territories of New Mexico and Arizona. In addition to their warlike ferocity, the Apache were intelligent, wily strategists. One U.S. general, whose identity has been lost, described the Apache as “the tigers of the human species,” although for the Apache themselves their nature was simply one born of the constant struggle to survive, and the guerrilla war tactics that they adopted came completely naturally to them. It was rumored that an Apache warrior could run for 50 miles without stopping.

The relationship between the Apache and the Pueblo people was peaceable enough. The Apache pitched their wickiup shelters on the outskirts of the Pueblo villages as they moved through in pursuit of wild game. However, the coming of the Spanish put an end to this existence. The Spanish slave traders had no compunction in hunting down captives to work in the silver mines of northern Mexico, and the Apache found in the Spanish a rich source of horses, guns, and captives of their own.

When, in 1870, the tribe were told that they had to stay on the reservation that had been allotted them, a particular band, under the leadership of Cochise, simply refused, and caused as much mayhem for the U.S. Government troops as they possibly could. In 1873 the troops had corraled some 3,000 Apaches and forced them onto the reservation. Unsurprisingly in view of such treatment, the Apache chose to continue fighting.

Perhaps the most famous of all Apache leaders was Geronimo, who led the tribe from 1880. However, even Geronimo had to admit defeat at the hands of the U.S. Government in 1886.

APACHE MEDICINE CRAZE

During the spring of 1882, Doklini, a popular medicine man of the Apache tribe who was otherwise known as “Attacking the Enemy,” otherwise Nabakelti, told his considerable number of followers who lived on the White Mountain Reservation in Arizona that he had had a vision, a divine revelation: the information imparted to Doklini revealed how the dead could be brought back to life.

At this time, the losses to Native Americans of all tribes are impossible to estimate; suffice to say that everyone must have been affected by the deaths of family, friends, and colleagues because of diseases, war, and starvation. Such a message of hope must have been inspiring, and the same emotions would hit those affected by the Ghost Dance Movement, which would gain momentum just a few short years later.

Doklini prepared some equipment that he needed for the miracle. He constructed 60 large wooden wheels painted with magical symbols, and also carved 12 sacred sticks. One of them, which he shaped into a cross, was given the title “Chief of Sticks.” Then he gathered 60 men from among his most fervent followers, and then Doklini started the dance.

When the time was right, Doklini went to the grave of a man, prominent among his people, who had died just a little while earlier. The medicine man and his followers danced around the grave and then disinterred the bones. They then danced a circle dance four times around these bones; this dance went on all that morning, and then the group chose another grave and repeated the ritual in the afternoon. A shelter of brush was placed over the bones in each instance.

The next set of instructions was then given by the medicine man. Everyone must pray for the next four mornings, he said; at the end of this time, the people to whom the bones belonged would be restored once more to life and vitality.

By the second morning of prayer, the small band of Apache, anticipating the restoration of two of their loved ones, were almost at the point of hysteria, convinced that Doklini’s medicine would have the desired effect.

Meanwhile, news of this interesting development had reached some of the Apache scouts who were based at Fort Apache, and were excused from their duties so that they could go and see what was happening. To the outside visitor, it must have appeared as though those waiting for their dead to be resurrected had gone crazy; this was the information that was relayed back to the fort. The presence of Doklini was requested, who responded by sealing the brush shelters over the bones tightly and suggesting, angrily, that he would appear to answer questions after two more days had passed. He also called together his people, explaining that the interruption meant that the bones might not reconstitute in the way he had promised, but that, because of the interference and interruption of the white men, the whole procedure might need to be repeated.

Doklini traveled to Fort Apache with something like an entourage: 62 dancers and all the equipment: the wheels, the sticks, and ceremonial drums. In all, it took the party nearly two days to reach their destination, stopping to dance along the way, and they made an encampment just above Fort Apache, dancing, drumming, and waiting for someone to come and see them. But no one came. After dancing and waiting all night, at dawn the party wended their way back home, arriving not long after dawn after a day and a half of traveling. Word came that the agent at Fort Apache was expecting them. Doklini replied that they had traveled to Fort Apache, no one came to see them, and that he wasn’t going to go all that way again.

The powers at Fort Apache decided to send a troop of 60 men to the small Apache settlement where Doklini and his band were based, with the purpose of arresting the old medicine man. Sixty men might seem extreme, given the task, but the agent was concerned that the Indians might resist the arrest of their spiritual leader.

In the event, neither Doklini nor his followers put up any resistance at all, and rode with the men to their temporary headquarters. There was no sign that there would be any trouble, but suddenly one of Doklini’s brothers, angered at the arrest, rode into the camp and killed the commanding officer with a single bullet. Seconds later, a soldier hit Doklini over the head with a blunt weapon; the old man was killed.

Knowing that a fight was looming, the soldiers hastily prepared their defenses. The Apache, outraged at the loss of Doklini, did indeed attack, and killed six of the soldiers. The pack animals escaped, but in the ensuing months the fighting caused deaths on both sides.

Had the authorities at Fort Apache not interfered, the chances are high that, after the fourth day, when none of the bones had been transformed into living men once more, the whole Apache Medicine Craze would have fizzled out, Doklini discredited, but no lives lost.

APACHE MOON

This was the term used by the white settlers for a full moon. The reason? Some of the Plains Indians—the Apache in particular—chose to attack by the light of the full moon, since there was a belief among the Apache that when a warrior died he would find in the afterlife the same conditions that he had left behind on the earthly plain. A raid undertaken under a moon-filled sky would have been very effective for the Apache attackers, and would also mean that any enemies that were killed would be destined to wander around in the half-light for all of eternity.

APALACHEE

When the explorer De Soto visited the Apalachee people at their territory in what is now known as Apalachee Bay in Florida, he found an industrious, hard-working people who were not only wealthy and skilled in agriculture, but had the reputation of being fierce warriors, too. When the tribe allied with the Spanish, they became the subject of raids from the Creek people, sent on behalf of the English Government. As a result, the Apalachee really began to suffer.

The worst was yet to come for this people, though. In 1703 the European colonists, accompanied by their Native American allies, conclusively raided the Apalachee territory and ransacked and burned all before them. More than 200 warriors were slaughtered and over 1,000 more were forced into slavery. Anyone lucky enough to survive fled, taking refuge with other peoples who were sympathetic to their plight.

Although there were reports of a few Apalachee still living in Louisiana in 1804, all that remains of the Apalachee today is remembered in some place names, including the bay in Florida mentioned earlier, and of course in the name of the Apalachian Mountains.

APPALOOSA

This is the name that the white men gave to the beautiful war ponies, with distinctive spotted coats, that belonged to the Nez Perce peoples. The name itself was derived from the area in which the people lived at one time, the Palouse Valley of the Palouse River, located in Oregon and Washington. The Nez Perce had been breeding, handling, and riding horses for at least 100 years before the Lewis and Clark Expedition “discovered” the tribe in the early 19th century. Although many of their Appaloosa ponies were killed in the latter part of the 1800s, the breed was revived in the latter part of the 20th century, and continues to flourish.

ARAPAHO

When the settlers first came upon them, the Arapaho were already expert horsemen and buffalo hunters. Their territory was originally what has become northern Minnesota, but the Arapaho relocated to the eastern Plains areas of Colorado and Wyoming at about the same time as the Cheyenne; because of this, the two people became associated and are also federally recognized as the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes. The Arapaho were also aligned with the Sioux.

The Arapaho tongue is part of the Algonquian language group. In later years—toward the end of the 1870s—the Northern Arapaho would be further relocated to the Wind River Reservation in Wyoming, while the Southern Arapaho went to live with the Cheyenne in Oklahoma. Despite this close association, which often meant intermarriage, each people retained its own customs and language. One major cultural difference between the two, for example, is that the Arapaho buried their dead in the ground, whereas the Cheyenne made a raftlike construction on which to lay their deceased, leaving birds and animals to devour the remains. The Arapaho were tipi dwellers, part of the Woodland Culture tribes. It was this group that were the originators of the Sun Dance. They also had a government of consensus.

Like other Native Americans, the Arapaho and the horse took to one another as though they’d been designed to; this meant that the tribe could travel further and faster, and also had the capability of carrying goods and chattels more efficiently than before. Fishing and hunting—which included hunting buffalo—provided much of what the Arapaho needed to survive.

In 1851, the First Fort Laramie Treaty set the boundaries of the Arapaho land, from the Arkansas River in the south to the North Platte in the north, and from the Continental Divide in the west to western Kansas and Nebraska. When gold was discovered near Denver in the late 1850s, contact with the settlers increased rapidly, and in 1861 there was an attempt to shift some of the Arapaho to a chunk of land along the Arkansas River. The Arapaho did not agree to this, however, and the treaty remained unenforceable in law. However, the matter escalated when in 1864 a peaceable band of Arapaho, camping along Sand Creek in the southeastern part of Colorado, were brutally attacked by a Colonel Chivington, who had wanted to prove himself a war hero. These Arapaho had no warning whatsoever. The Sand Creek Massacre, as it came to be known, included the slaughter of women, children, and elderly people, and ignited angry conflict in the mid 1860s. Rather than giving him heroic status, the matter brought shame to Chivington. Eventually, treaties were agreed that saw the Southern Arapaho settling in west central Oklahoma.