По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

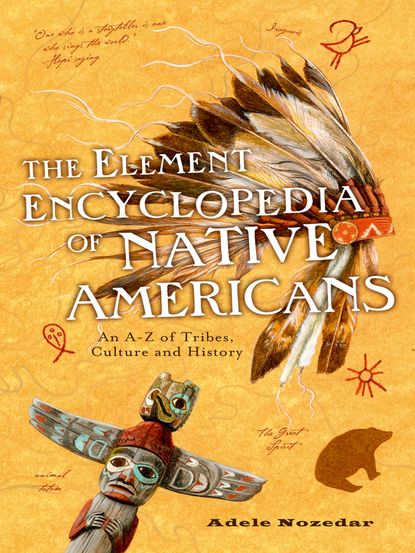

The Element Encyclopedia of Native Americans: An A to Z of Tribes, Culture, and History

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

This is also known as The Dawes Act, after Senator Henry Dawes of Massachusetts, who was its main proponent. Passed in 1887, the Act gave the President of the United States the right to audit all the lands that belonged to the Native American peoples, and then, where necessary, divide that land into smaller pieces for individual tribes. The overarching aim of the Act was to aid the assimilation of Native Americans into the white majority; individual ownership of land was perceived to be of paramount importance in facilitating this aim. The European sensibility placed a lot of importance on land and property ownership, while this was not a primary concern of the Native peoples, who believed that the land belonged to everyone. As well as apportioning parcels of land, the Act enabled the Government to buy any “excess” land from the Native Americans, and then apportion that land to others—primarily, white settlers.

Dawes was very much of the mind that ownership of land would have a “civilizing” effect on the Native Americans. In order to be civilized, he said, a man had to:

“… wear civilized clothes … cultivate the ground, live in houses, ride in Studebaker wagons, send children to school, drink whiskey and own property …”

The key points of the Act were as follows:

The head of a family would be allotted 160 acres; an orphan or a single person under the age of 18 would receive 80 acres; and anyone else under the age of 18 would receive 40 acres.

These allotted chunks of land would be held in trust by the U.S. Government for 25 years.

Native Americans could choose their own land, and had four years to do so. If they still had not made a decision after this time, then they would have to take what they were given.

Further, any Native American who had received land and who had subsequently “adopted the habits of a civilized life” would be made a citizen of the United States.

Excluded from the Act at the time it was passed were the Cherokee, Creek, Choctaw, Chickasaw, Seminole, Miami, and Peopria, who were living in the Indian Territory, also the Osage, Sauk and Fox in the Oklahoma Territory, and any of the Seneca in New York.

The Act was not universally admired by any means, certainly not by the Native Americans whose traditional way of living, sharing the land and its bounty, was completely ignored. It was also looked upon with a great deal of suspicion and cynicism by many of European descent. Senator Henry M. Teller of Colorado spoke for many when he said that the real purpose of the Allotment policy was:

“… to despoil the Indians of their lands and to make them vagabonds on the face of the earth …”

Teller also pointed out that:

“… The provisions for the apparent benefit of the Indians are but the pretext to get at his lands and occupy them … If this were done in the name of Greed, it would be bad enough; but to do it in the name of Humanity … is infinitely worse …”

Teller was proved right. The amount of land given to individuals was not sufficient for them to subsist in the ways that they had done for generations, and effectively saw the end of the traditional way of hunting. It also forced the Native Americans to become farmers instead. A further complication came about in that, if the owner of the land died, the allotment could be divided into even smaller chunks by his heirs. After 25 years the Native had the right to sell the land, and the result was that much of it was bought by white settlers for bargain-basement prices. It was also sold to the railroad companies and other major organizations, as Teller had predicted.

The amount of land originally owned by Native Americans was estimated at some 150,000,000 acres; fewer than 15 years after the Act, in 1900, this had been reduced to 78,000,000 acres.

The Allotment Act was abolished in 1934, as no longer deemed necessary.

AMERICAN HORSE

1840-1908

An Oglala Sioux chief and son of Sitting Bear, American Horse’s Native name was Wasicun Thasunke, meaning “he who has the horse of a white man.” He also had the nickname “Spider.” Other illustrious members of his family include his uncle, also American Horse, and his father-in-law, Red Cloud. He also fought alongside Crazy Horse and, in later years, became a performer in Buffalo Bill Cody’s Wild West Show.

American Horse became Shirt-wearer, or chief, along with Crazy Horse, Young Man Afraid of His Horses, and He Dog, in 1868. In 1887 American Horse was one of the chiefs who signed a treaty between the U.S. Government and the Sioux, which essentially reduced the Sioux territory in Dakota by half, a ruling which, not surprisingly, was vehemently opposed by over half the Oglala. At the same time the unrest was reflected in the burgeoning Ghost Dance Movement, and further exacerbated by the murder of Sitting Bull. However, the potential uprising against the Federal Government by the Oglala was deflected by American Horse, who persuaded them to adhere to the terms outlined by the treaty in the name of peace; consequently, the tribe settled at the Pine Ridge Reservation. American Horse campaigned for fair treatment of the Sioux—including better rations—in accordance with what had been agreed.

A great advocate of education, American Horse believed that Native Americans would do well to be schooled according to the white man’s ways; his son and nephew were among the first to attend the controversial Carlisle School.

American Horse died peacefully at Pine Ridge in 1908.

AMERICAN INDIAN MOVEMENT

Also known by the acronym AIM, this organization was founded in Minneapolis in 1968 as a focus for numerous issues that concerned the Native American community. It followed on from the Red Power movement.

The issues concerning AIM included housing, police harassment toward those of Native American origin, poverty, and also the outstanding issues concerning treaties between the Native peoples and the U.S. Government. Although the movement started in Minneapolis, it soon gained momentum across the United States, and in 1971 members gathered together to protest in Washington, D.C.

The “Trail of Broken Treaties” saw the Native American representatives present a list to the Government of 20 demands that they felt they were entitled to, due to various promises that had been made in historical agreements. These 20 items were:

Restore treaty-making (ended by Congress in 1871)

Establish a treaty commission to make new treaties (with sovereign Native Nations)

Provide opportunities for Indian leaders to address Congress directly

Review treaty commitments and violations

Have any unratified treaties reviewed by the Senate

Ensure that all American Indians are governed by treaty relations

Provide relief to Native Nations as compensation for treaty rights violations

Recognize the right of Indians to interpret treaties

Create a Joint Congressional Committee to reconstruct relations with Indians

Restore 110 million acres of land taken away from Native Nations by the United States

Restore terminated rights of Native Nations

Repeal state jurisdiction on Native Nations

Provide Federal protection for offenses against Indians

Abolish the Bureau of Indian Affairs

Create a new office of Federal Indian Relations

Remedy breakdown in the constitutionally prescribed relationships between the United States and Native Nations

Ensure immunity of Native Nations from state commerce regulation, taxes, and trade restrictions

Protect Indian religious freedom and cultural integrity

Establish national Indian voting with local options; free national Indian organizations from governmental controls

Reclaim and affirm health, housing, employment, economic development, and education for all Indian people.

Perhaps the most noteworthy piece of activism by AIM was “The Longest Walk.” Following a spiritual tradition with political aims in mind, The Longest Walk began in February 1978 with a ceremony on Alcatraz Island, where the Red Power movement had first drawn attention to the plight of Native Americans ten years earlier. The beginning of the Walk started with a pipe ceremony; this pipe was carried the entire length of the route, some 3,200 miles across the U.S.A., ending in Washington, D.C. in July of the same year.

The walk highlighted many issues, such as the need for tribal sovereignty and the civil rights of the Native American people. Support was garnered from both within the Native community and outside of it; and from both inside the United States and from much further afield.

Once in Washington, the pipe, which had been loaded with tobacco at the beginning of the journey, was smoked at the site of the Washington Monument. Thereafter, rallies were held to highlight all the issues that The Longest Walk had set out to address.

AIM continues to fight on behalf of the Native American peoples.