По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

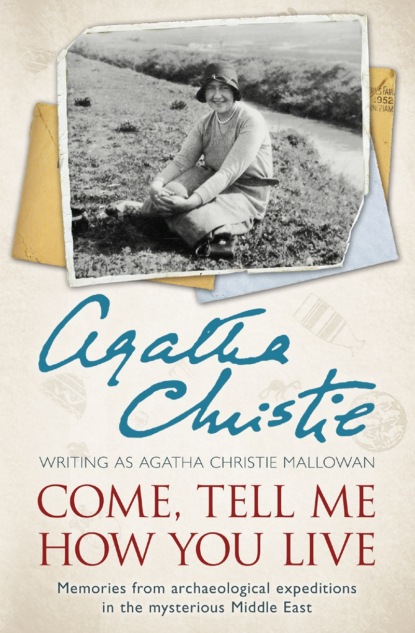

Come, Tell Me How You Live: An Archaeological Memoir

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

Finally the old man inquires Max’s name. Max tells it him. He considers it.

‘Milwan,’ he repeats. ‘Milwan… How light! How bright! How beautiful!’

He sits with us a little longer. Then, as quietly as he has come, he leaves us. We never see him again.

Restored to health, I now really begin to enjoy myself. We start every morning at early dawn, examining each mound as we come to it, walking round and round it, picking up any sherds of pottery. Then we compare results on the top, and Max keeps such specimens as are useful, putting them in a little linen bag and labelling them.

There is a great competition between us as to who gets the prize find of the day.

I begin to understand why archaeologists have a habit of walking with eyes downcast to the ground. Soon, I feel, I myself shall forget to look around me, or out to the horizon. I shall walk looking down at my feet as though there only any interest lies.

I am struck as often before by the fundamental difference of race. Nothing could differ more widely than the attitude of our two chauffeurs to money. Abdullah lets hardly a day pass without clamouring for an advance of salary. If he had had his way he would have had the entire amount in advance, and it would, I rather imagine, have been dissipated before a week was out. With Arab prodigality Abdullah would have splashed it about in the coffee-house. He would have cut a figure! He would have ‘made a reputation for himself’.

Aristide, the Armenian, has displayed the greatest reluctance to have a penny of his salary paid him. ‘You will keep it for me, Khwaja, until the journey is finished. If I want money for some little expense I will come to you.’ So far he has demanded only fourpence of his salary—to purchase a pair of socks!

His chin is now adorned by a sprouting beard, which makes him look quite a Biblical figure. It is cheaper, he explains, not to shave. One saves the money one might have to spend on a razor blade. And it does not matter here in the desert.

At the end of the trip Abdullah will be penniless once more, and will doubtless be again adorning the water-front of Beyrout, waiting with Arab fatalism for the goodness of God to provide him with another job. Aristide will have the money he has earned untouched.

‘And what will you do with it?’ Max asks him.

‘It will go towards buying a better taxi,’ replies Aristide.

‘And when you have a better taxi?’

‘Then I shall earn more and have two taxis.’

I can quite easily foresee returning to Syria in twenty years’ time, and finding Aristide the immensely rich owner of a large garage, and probably living in a big house in Beyrout. And even then, I dare say, he will avoid shaving in the desert because it saves the price of a razor blade.

And yet, Aristide has not been brought up by his own people. One day, as we pass some Beduin, he is hailed by them, and cries back to them, waving and shouting affectionately.

‘That,’ he explains, ‘is the Anaizah tribe, of whom I am one.’

‘How is that?’ Max asks.

And then Aristide, in his gentle, happy voice, with his quiet, cheerful smile, tells the story. The story of a little boy of seven, who with his family and other Armenian families was thrown by the Turks alive into a deep pit. Tar was poured on them and set alight. His father and mother and two brothers and sisters were all burnt alive. But he, who was below them all, was still alive when the Turks left, and he was found later by some of the Anaizah Arabs. They took the little boy with them and adopted him into the Anaizah tribe. He was brought up as an Arab, wandering with them over their pastures. But when he was eighteen he went into Mosul, and there demanded that papers be given him to show his nationality. He was an Armenian, not an Arab! Yet the blood brotherhood still holds, and to members of the Anaizah he still is one of them.

Hamoudi and Max are very gay together. They laugh and sing and cap stories. Sometimes I ask for a translation when the mirth is particularly hilarious. There are moments when I feel envious of the fun they are having. Mac is still separated from me by an impassable barrier. We sit together at the back of the car in silence. Any remark I make is considered gravely on its merits by Mac and disposed of accordingly. Never have I felt less of a social success! Mac, on the other hand, seems quite happy. There is about him a beautiful self-sufficiency which I cannot but admire.

Nevertheless, when, encased in my sleeping-bag at night in the privacy of our tent, I hold forth to Max on the incidents of the day, I strenuously maintain that Mac is not quite human!

When Mac does advance an original comment it is usually of a damping nature. Adverse criticism seems to afford him a definite gloomy satisfaction.

Am perplexed today by the growing uncertainty of my walking powers. In some curious way my feet don’t seem to match. I am puzzled by a decided list to port. Is it, I wonder fearfully, the first symptom of some tropical disease?

I ask Max if he has noticed that I can’t walk straight.

‘But you never drink,’ he replies. ‘Heaven knows,’ he adds reproachfully, ‘I’ve tried hard enough with you.’

This introduces a second and controversial subject. Every-one struggles through life with some unfortunate disability. Mine is to be unable to appreciate either alcohol or tobacco.

If I could only bring myself to disapprove of these essential products my self-respect would be saved. But, on the contrary, I look with envy at self-possessed women flipping cigarette ash here, there and everywhere, and creep miserably round the room at cocktail parties finding a place to hide my untasted glass.

Perseverance has not availed. For six months I religiously smoked a cigarette after lunch and after dinner, choking a little, biting fragments of tobacco, and blinking as the ascending smoke pricked my eyelids. Soon, I told myself, I should learn to like smoking. I did not learn to like it, and my performance was criticized severely as being inartistic and painful to watch. I accepted defeat.

When I married Max we enjoyed the pleasures of the table in perfect harmony, eating wisely but much too well. He was distressed to find that my appreciation of good drink—or, indeed, of any drink—was nil. He set to work to educate me, trying me perseveringly with clarets, burgundies, sauternes, graves, and, more desperately, with tokay, vodka, and absinthe! In the end he acknowledged defeat. My only reaction was that some tasted worse than others! With a weary sigh, Max contemplated a life in which he should be for ever condemned to the battle of obtaining water for me in a restaurant! It has added, he says, years to his life.

Hence his remarks when I enlist his sympathy for my drunken progress.

‘I seem,’ I explain, ‘to be always falling over to the left.’

Max says it is probably one of these very rare tropical diseases that are distinguished by just being called by somebody’s name. Stephenson’s disease—or Hartley’s. The sort of thing, he goes on cheerfully, which will probably end with your toes falling off one by one.

I contemplate this pleasing prospect. Then it occurs to me to look at my shoes. The mystery is at once explained. The outer sole of my left foot and the inner sole of the right foot are worn right down. As I stare at them the full solution dawns on me. Since leaving Der-ez-Zor I have walked round about fifty mounds, at different levels, on the side of a steep slope, but always with the hill on my left. All that is needed is to go into reverse, and go round mounds to the right instead of the left. In due course my shoes will then be worn even.

Today we arrive at Tell Ajaja, the former Arban, a large and important Tell.

The main track from Der-ez-Zor joins in near here, so we feel now we are practically on a main road. Actually we pass three cars, all going hell-for-leather in the direction of Der-ez-Zor!

Small clusters of mud houses adorn the Tell, and various people pass the time of day with us upon the big mound. This is practically civilization. Tomorrow we shall arrive at Hasetshe, the junction of the Habur and the Jaghjagha. There we shall be in civilization. It is a French military post, and an important town in this part of the world. There I shall have my first sight of the legendary and long-promised Jaghjagha river! I feel quite excited.

Our arrival at Hasetshe is full of excitement! It is an unattractive place, with streets and a few shops and a post office. We pay two ceremonious visits—one to the Military and one to the Post Office.

The French Lieutenant is most kind and helpful. He offers us hospitality, but we assure him that our tents are quite comfortable where we have pitched them by the river bank. We accept, however, an invitation to dinner on the following day. The Post Office, where we go for letters, is a longer business. The Postmaster is out, and everything is consequently locked up. However, a small boy goes in search of him, and in due course (half an hour!) he arrives, full of urbanity, bids us welcome to Hasetshe, orders coffee for us, and only after a prolonged exchange of compliments comes to the business in hand—letters.

‘But there is no hurry,’ he says, beaming. ‘Come again tomorrow. I shall be delighted to entertain you.’

‘Tomorrow,’ Max says, ‘we have work to do. We should like our letters tonight.’

Ah, but here is the coffee! We sit and sip. At long last, after polite exhortations, the Postmaster unlocks his private office and starts to search. In the generosity of his heart he urges on us additional letters addressed to other Europeans. ‘You had better have these,’ he says. ‘They have been here six months. No one has come for them. Yes, yes, surely they will be for you.’

Politely but firmly we refuse the correspondence of Mr Johnson, M. Mavrogordata, and Mr Pye. The Postmaster is disappointed.

‘So few?’ he says. ‘But come, will you not have this large one here?’

But we insist on sticking strictly to those letters and papers that bear our own names. A money order has come, as arranged, and Max now goes into the question of cashing it. This, it seems, is incredibly complicated. The Postmaster has never seen a money order before, we gather, and is very properly suspicious of it. He calls in two assistants, and the question is debated thoroughly, though with great good humour. Here is something entirely novel and delightful on which everyone can have a different opinion.

The matter is finally settled and various forms signed when the discovery is made that there is no actual cash in the Post Office! This, the Postmaster says, can be remedied on the morrow! He will send out and collect it from the Bazaar.

We leave the Post Office somewhat exhausted, and walk back to the spot by the river which we have chosen—a little way from the dust and dirt of Hasetshe. A sad spectacle greets us. ’Isa, the cook, is sitting by the cooking-tent, his head in his hands, weeping bitterly.

What has happened?

Alas, he replies, he is disgraced. Little boys have collected round to jeer at him. His honour has gone! In a moment of inattention dogs have devoured the dinner he had prepared. There is nothing left, nothing at all but some rice.

Gloomily we eat plain rice, whilst Hamoudi, Aristide and Abdullah reiterate to the wretched ’Isa that the principal duty of a cook is never to let his attention wander from the dinner he is cooking until the moment when that dinner is safely set before those for whom it is destined.

’Isa says that he feels he is unequal to the strain of being a cook. He has never been one before (‘That explains a good deal!’ says Max), and would prefer to go into a garage. Will Max give him a recommendation as a first-class driver?