По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

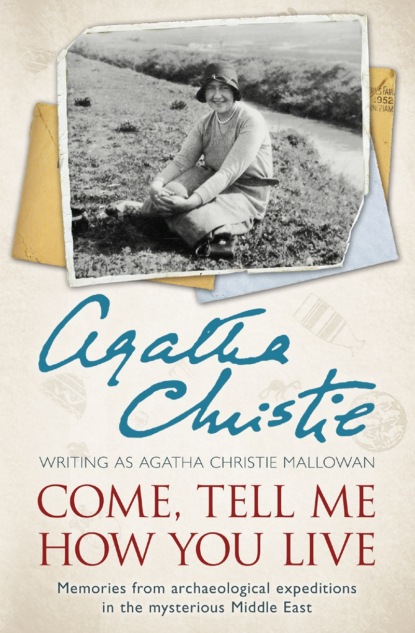

Come, Tell Me How You Live: An Archaeological Memoir

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

We go forthwith to look at our lorry—a Ford chassis, to which a native body is being built. We have had to fall back on this as no second-hand one was to be obtained in sufficiently good condition.

The bodywork seems definitely optimistic, of the Inshallah nature, and the whole thing has a high and dignified appearance that is suspiciously too good to be true. Max is a little worried at the non-appearance of Hamoudi, who was to have met us in Beyrout by this date.

Mac scorns to look at the town and returns to his bedroom to sit on his rug and write in his diary. Interested speculation on my part as to what he writes in the diary.

An early awakening. At five a.m. our bedroom door opens, and a voice announces in Arabic: ‘Your foremen have come!’

Hamoudi and his two sons surge into the room with the eager charm that distinguishes them, seizing our hands, pressing them against their foreheads. ‘Shlon kefek?’ (How is your comfort?) ‘Kullish zen.’ (Very well.) ‘El hamdu lillah! El hamdu lillah!’ (We all praise God together!)

Shaking off the mists of sleep, we order tea, and Hamoudi and his sons squat down comfortably on the floor and proceed to exchange news with Max. The language barrier excludes me from this conversation. I have used all the Arabic I know. I long wistfully for sleep, and even wish that the Hamoudi family had postponed their greetings to a more seasonable hour. Still, I realize that to them it is the most natural thing in the world thus to arrive.

Tea dispels the mists of sleep, and Hamoudi addresses various remarks to me, which Max translates, as also my replies. All three of them beam with happiness, and I realize anew what very delightful people they are.

Preparations are now in full swing—buying of stores; engaging of a chauffeur and cook; visits to the Service des Antiquités; a delightful lunch with M. Seyrig, the Director, and his very charming wife. Nobody could be kinder to us than they are—and, incidentally, the lunch is delicious.

Disagreeing with the Turkish douanier’s opinion that I have too many shoes, I proceed to buy more shoes! Shoes in Beyrout are a delight to buy. If your size is not available, they are made for you in a couple of days—of good leather, perfectly fitting. It must be admitted that buying shoes is a weakness of mine. I shall not dare to return home through Turkey!

We wander through the native quarters and buy interesting lengths of material—a kind of thick white silk, embroidered in golden thread or in dark blue. We buy silk abas to send home as presents. Max is fascinated with all the different kinds of bread. Anyone with French blood in him loves good bread. Bread to a Frenchman means more than any other kind of food. I have heard an officer of the Services Spéciaux say of a colleague in a lonely frontier outpost: ‘Ce pauvre garçon! Il n’a même pas de pain là bas, seulement la galette Kurde!’ with deep and heartfelt pity.

We also have long and complicated dealings with the Bank. I am struck, as always in the East, with the reluctance of banks to do any business whatever. They are polite, charming, but anxious to evade any actual transaction. ‘Oui, oui!’ they murmur sympathetically. ‘Ecrivez une letter!’ And they settle down again with a sigh of relief at having postponed any action.

When action has been reluctantly forced upon them, they take revenge by a complicated system of ‘les timbres’. Every document, every cheque, every transaction whatever, is held up and complicated by a demand for ‘les timbres’. Continual small sums are disbursed. When everything is, as you think, finished, once more comes a hold-up!

‘Et deux francs cinquante centimes pour les timbres, s’il vous plaît.’

Still, at last transactions are completed, innumerable letters are written, incredible numbers of stamps are affixed. With a sigh of relief the Bank clerk sees a prospect of finally getting rid of us. As we leave the Bank, we hear him say firmly to another importunate client: ‘Ecrivez une lettre, s’il vous plaît.’

There still remains the engaging of a cook and chauffeur.

The chauffeur problem is solved first. Hamoudi arrives, beaming, and informs us that we are in good fortune—he has secured for us an excellent chauffeur.

How, Max asks, has Hamoudi obtained this treasure?

Very simply, it appears. He was standing on the water-front, and having had no job for some time, and being completely destitute, he will come very cheap. Thus, at once, we have effected an economy!

But is there any means of knowing whether he is a good chauffeur? Hamoudi waves such a question aside. A baker is a man who puts bread in an oven and bakes it. A chauffeur is a man who takes a car out and drives it!

Max, without any undue enthusiasm, agrees to engage Abdullah if nothing better offers, and Abdullah is summoned to an interview. He bears a remarkable resemblance to a camel, and Max says with a sigh that at any rate he seems stupid, and that is always satisfactory. I ask why, and Max says because he won’t have the brains to be dishonest.

On our last afternoon in Beyrout, we drive out to the Dog River, the Nahr el Kelb. Here, in a wooded gully running inland, is a café where you can drink coffee, and then wander pleasantly along a shady path.

But the real fascination of the Nahr el Kelb lies in the carved inscriptions on the rock where a pathway leads up to the pass over the Lebanon. For here, in countless wars, armies have marched and left their record. Here are Egyptian hieroglyphics—of Rameses II—and boasts made by Assyrian and Babylonian armies. There is the figure of Tiglathpileser I. Sennacherib left an inscription in 701 B.C. Alexander passed and left his record. Esarhaddon and Nebuchadnezzar have commemorated their victories and finally, linking up with antiquity, Allenby’s army wrote names and initials in 1917. I never tire of looking at that carved surface of rock. Here is history made manifest…

I am so far carried away as to remark enthusiastically to Mac that it is really very thrilling, and doesn’t he think so?

Mac raises his polite eyebrows, and says in a completely uninterested voice that it is, of course, very interesting…

The arrival and loading up of our lorry is the next excitement. The body of the lorry looks definitely top-heavy. It sways and dips, but has withal such an air of dignity—indeed of majesty—that it is promptly christened Queen Mary.

In addition to Queen Mary we hire a ‘taxi’—a Citröen, driven by an amiable Armenian called Aristide. We engage a somewhat melancholy-looking cook (’Isa), whose testimonials are so good as to be highly suspicious. And finally, the great day comes, and we set out—Max, Hamoudi, myself, Mac, Abdullah, Aristide and ’Isa—to be companions, for better, for worse, for the next three months.

Our first discovery is that Abdullah is quite the worst driver imaginable, our second is that the cook is a pretty bad cook, our third is that Aristide is a good driver but has an incredibly bad taxi!

We drive out of Beyrout along the coast road. We pass the Nahr el Kelb, and continue on with the sea on our left. We pass small clusters of white houses and entrancing little sandy bays, and small coves between rocks. I long to stop and bathe, but we have started now on the real business of life. Soon, too soon, we shall turn inland from the sea, and after that, for many months, we shall not see the sea again.

Aristide honks his horn ceaselessly in the Syrian fashion. Behind us Queen Mary is following, dipping and bending like a ship at sea with her top-heavy bodywork.

We pass Byblos, and now the little clusters of white houses are few and far between. On our right is the rocky hillside.

And at last we turn off and strike inland for Homs.

There is a good hotel at Homs—a very fine hotel, Hamoudi has told us.

The grandeur of the hotel proves to be mainly in the building itself. It is spacious, with immense stone corridors. Its plumbing, alas, is not functioning very well! Its vast bedrooms contain little in the way of comfort. We look at ours respectfully, and then Max and I go out to see the town. Mac, we find, is sitting on the side of his bed, folded rug beside him, writing earnestly in his diary.

(What does Mac put in his diary? He displays no enthusiasm to have a look at Homs.)

Perhaps he is right, for there is not very much to see.

We have a badly cooked pseudo-European meal and retire to bed.

Yesterday we were travelling within the confines of civilization. Today, abruptly, we leave civilization behind. Within an hour or two there is no green to be seen anywhere. Everything is brown sandy waste. The tracks seem confusing. Sometimes at rare intervals we meet a lorry that comes up suddenly out of nothingness.

It is very hot. What with the heat and the unevenness of the track and the badness of the taxi’s springs, and the dust that you swallow and which makes your face stiff and hard, I start a furious headache.

There is something frightening, and yet fascinating, about this vast world denuded of vegetation. It is not flat like the desert between Damascus and Baghdad. Instead, you climb up and down. It feels a little as though you had become a grain of sand among the sand-castles you built on the beach as a child.

And then, after seven hours of heat and monotony and a lonely world—Palmyra!

That, I think, is the charm of Palmyra—its slender creamy beauty rising up fantastically in the middle of hot sand. It is lovely and fantastic and unbelievable, with all the theatrical implausibility of a dream. Courts and temples and ruined columns…

I have never been able to decide what I really think of Palmyra. It has always for me the dream-like quality of that first vision. My aching head and eyes made it more than ever seem a feverish delusion! It isn’t—it can’t be—real.

But suddenly we are in the middle of people—a crowd of cheerful French tourists, laughing and talking and snapping cameras. We pull up in front of a handsome building—the Hotel.

Max warns me hurriedly: ‘You mustn’t mind the smell. It takes a little getting used to.’

It certainly does! The Hotel is charming inside, arranged with real taste and charm. But the smell of stale water in the bedroom is very strong.

‘It’s quite a healthy smell,’ Max assures me.

And the charming elderly gentleman, who is, I understand, the Hotel proprietor, says with great emphasis:

‘Mauvaise odeur, oui! Malsain, non!’

So that is settled! And, anyway, I do not care. I take aspirin and drink tea and lie down on the bed. Later, I say, I will do sight-seeing—just now I care for nothing but darkness and rest.

Inwardly I feel a little dismayed. Am I going to be a bad traveller—I, who have always enjoyed motoring?