По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2024.

✖

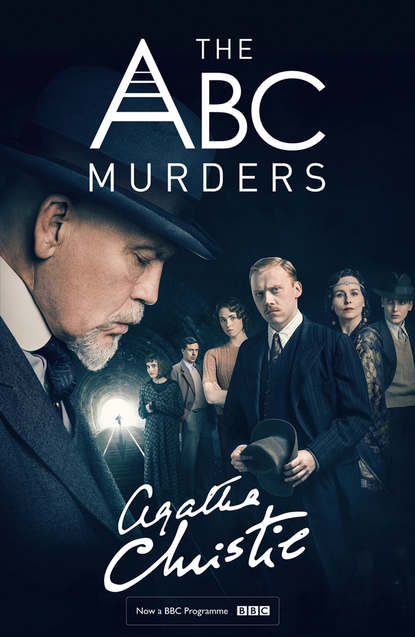

The ABC Murders

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

We made our way through the crowd and accosted the young policeman. Poirot produced the credentials which the inspector had given him. The constable nodded, and unlocked the door to let us pass within. We did so and entered to the intense interest of the lookers-on.

Inside it was very dark owing to the shutters being closed. The constable found and switched on the electric light. The bulb was a low-powered one so that the interior was still dimly lit.

I looked about me.

A dingy little place. A few cheap magazines strewn about, and yesterday’s newspapers—all with a day’s dust on them. Behind the counter a row of shelves reaching to the ceiling and packed with tobacco and packets of cigarettes. There were also a couple of jars of peppermint humbugs and barley sugar. A commonplace little shop, one of many thousand such others.

The constable in his slow Hampshire voice was explaining the mise en scène.

‘Down in a heap behind the counter, that’s where she was. Doctor says as how she never knew what hit her. Must have been reaching up to one of the shelves.’

‘There was nothing in her hand?’

‘No, sir, but there was a packet of Player’s down beside her.’

Poirot nodded. His eyes swept round the small space observing—noting.

‘And the railway guide was—where?’

‘Here, sir.’ The constable pointed out the spot on the counter. ‘It was open at the right page for Andover and lying face down. Seems as though he must have been looking up the trains to London. If so, it mightn’t have been an Andover man at all. But then, of course, the railway guide might have belonged to someone else what had nothing to do with the murder at all, but just forgot it here.’

‘Fingerprints?’ I suggested.

The man shook his head.

‘The whole place was examined straight away, sir. There weren’t none.’

‘Not on the counter itself?’ asked Poirot.

‘A long sight too many, sir! All confused and jumbled up.’

‘Any of Ascher’s among them?’

‘Too soon to say, sir.’

Poirot nodded, then asked if the dead woman lived over the shop.

‘Yes, sir, you go through that door at the back, sir. You’ll excuse me not coming with you, but I’ve got to stay—’

Poirot passed through the door in question and I followed him. Behind the shop was a microscopic sort of parlour and kitchen combined—it was neat and clean but very dreary looking and scantily furnished. On the mantelpiece were a few photographs. I went up and looked at them and Poirot joined me.

The photographs were three in all. One was a cheap portrait of the girl we had been with that afternoon, Mary Drower. She was obviously wearing her best clothes and had the self-conscious, wooden smile on her face that so often disfigures the expression in posed photography, and makes a snapshot preferable.

The second was a more expensive type of picture—an artistically blurred reproduction of an elderly woman with white hair. A high fur collar stood up round the neck.

I guessed that this was probably the Miss Rose who had left Mrs Ascher the small legacy which had enabled her to start in business.

The third photograph was a very old one, now faded and yellow. It represented a young man and woman in somewhat old-fashioned clothes standing arm in arm. The man had a button-hole and there was an air of bygone festivity about the whole pose.

‘Probably a wedding picture,’ said Poirot. ‘Regard, Hastings, did I not tell you that she had been a beautiful woman?’

He was right. Disfigured by old-fashioned hairdressing and weird clothes, there was no disguising the handsomeness of the girl in the picture with her clear-cut features and spirited bearing. I looked closely at the second figure. It was almost impossible to recognise the seedy Ascher in this smart young man with the military bearing.

I recalled the leering drunken old man, and the toil-worn face of the dead woman—and I shivered a little at the remorselessness of time…

From the parlour a stair led to two upstairs rooms. One was empty and unfurnished, the other had evidently been the dead woman’s bedroom. After being searched by the police it had been left as it was. A couple of old worn blankets on the bed—a little stock of well-darned underwear in a drawer—cookery recipes in another—a paper-backed novel entitled The Green Oasis—a pair of new stockings—pathetic in their cheap shininess—a couple of china ornaments—a Dresden shepherd much broken, and a blue and yellow spotted dog—a black raincoat and a woolly jumper hanging on pegs—such were the worldly possessions of the late Alice Ascher.

If there had been any personal papers, the police had taken them.

‘Pauvre femme,’ murmured Poirot. ‘Come, Hastings, there is nothing for us here.’

When we were once more in the street, he hesitated for a minute or two, then crossed the road. Almost exactly opposite Mrs Ascher’s was a greengrocer’s shop—of the type that has most of its stock outside rather than inside.

In a low voice Poirot gave me certain instructions. Then he himself entered the shop. After waiting a minute or two I followed him in. He was at the moment negotiating for a lettuce. I myself bought a pound of strawberries.

Poirot was talking animatedly to the stout lady who was serving him.

‘It was just opposite you, was it not, that this murder occurred? What an affair! What a sensation it must have caused you!’

The stout lady was obviously tired of talking about the murder. She must have had a long day of it. She observed:

‘It would be as well if some of that gaping crowd cleared off. What is there to look at, I’d like to know?’

‘It must have been very different last night,’ said Poirot. ‘Possibly you even observed the murderer enter the shop—a tall, fair man with a beard, was he not? A Russian, so I have heard.’

‘What’s that?’ The woman looked up sharply. ‘A Russian did it, you say?’

‘I understand that the police have arrested him.’

‘Did you ever know?’ The woman was excited, voluble. ‘A foreigner.’

‘Mais oui. I thought perhaps you might have noticed him last night?’

‘Well, I don’t get much chance of noticing, and that’s a fact. The evening’s our busy time and there’s always a fair few passing along and getting home after their work. A tall, fair man with a beard—no, I can’t say I saw anyone of that description anywhere about.’

I broke in on my cue.

‘Excuse me, sir,’ I said to Poirot. ‘I think you have been misinformed. A short dark man I was told.’

An interested discussion intervened in which the stout lady, her lank husband and a hoarse-voiced shop-boy all participated. No less than four short dark men had been observed, and the hoarse boy had seen a tall fair one, ‘but he hadn’t got no beard,’ he added regretfully.

Finally, our purchases made, we left the establishment, leaving our falsehoods uncorrected.

‘And what was the point of all that, Poirot?’ I demanded somewhat reproachfully.

‘Parbleu, I wanted to estimate the chances of a stranger being noticed entering the shop opposite.’

‘Couldn’t you simply have asked—without all that tissue of lies?’