По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

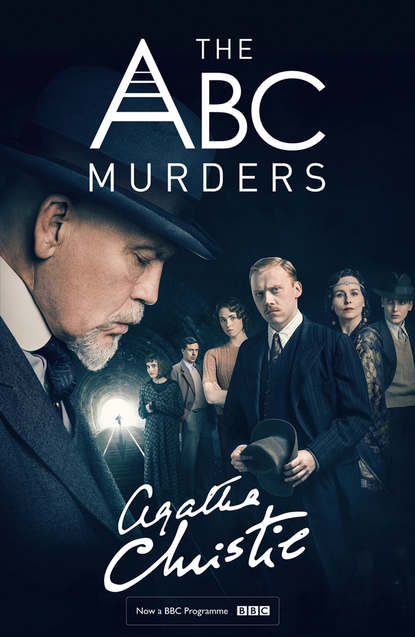

The ABC Murders

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘No, mon ami. If I had “simply asked”, as you put it, I should have got no answer at all to my questions. You yourself are English and yet you do not seem to appreciate the quality of the English reaction to a direct question. It is invariably one of suspicion and the natural result is reticence. If I had asked those people for information they would have shut up like oysters. But by making a statement (and a somewhat out of the way and preposterous one) and by your contradiction of it, tongues are immediately loosened. We know also that that particular time was a “busy time”—that is, that everyone would be intent on their own concerns and that there would be a fair number of people passing along the pavements. Our murderer chose his time well, Hastings.’

He paused and then added on a deep note of reproach:

‘Is it that you have not in any degree the common sense, Hastings? I say to you: “Make a purchase quelconque”—and you deliberately choose the strawberries! Already they commence to creep through their bag and endanger your good suit.’

With some dismay, I perceived that this was indeed the case.

I hastily presented the strawberries to a small boy who seemed highly astonished and faintly suspicious.

Poirot added the lettuce, thus setting the seal on the child’s bewilderment.

He continued to drive the moral home.

‘At a cheap greengrocer’s—not strawberries. A strawberry, unless fresh picked, is bound to exude juice. A banana—some apples—even a cabbage—but strawberries—’

‘It was the first thing I thought of,’ I explained by way of excuse.

‘That is unworthy of your imagination,’ returned Poirot sternly.

He paused on the sidewalk.

The house and shop on the right of Mrs Ascher’s was empty. A ‘To Let’ sign appeared in the windows. On the other side was a house with somewhat grimy muslin curtains.

To this house Poirot betook himself and, there being no bell, executed a series of sharp flourishes with the knocker.

The door was opened after some delay by a very dirty child with a nose that needed attention.

‘Good evening,’ said Poirot. ‘Is your mother within?’

‘Ay?’ said the child.

It stared at us with disfavour and deep suspicion.

‘Your mother,’ said Poirot.

This took some twelve seconds to sink in, then the child turned and, bawling up the stairs ‘Mum, you’re wanted,’ retreated to some fastness in the dim interior.

A sharp-faced woman looked over the balusters and began to descend.

‘No good you wasting your time—’ she began, but Poirot interrupted her.

He took off his hat and bowed magnificently.

‘Good evening, madame. I am on the staff of the Evening Flicker. I want to persuade you to accept a fee of five pounds and let us have an article on your late neighbour, Mrs Ascher.’

The irate words arrested on her lips, the woman came down the stairs smoothing her hair and hitching at her skirt.

‘Come inside, please—on the left there. Won’t you sit down, sir.’

The tiny room was heavily over-crowded with a massive pseudo-Jacobean suite, but we managed to squeeze ourselves in and on to a hard-seated sofa.

‘You must excuse me,’ the woman was saying. ‘I am sure I’m sorry I spoke so sharp just now, but you’d hardly believe the worry one has to put up with—fellows coming along selling this, that and the other—vacuum cleaners, stockings, lavender bags and such-like foolery—and all so plausible and civil spoken. Got your name, too, pat they have. It’s Mrs Fowler this, that and the other.’

Seizing adroitly on the name, Poirot said:

‘Well, Mrs Fowler, I hope you’re going to do what I ask.’

‘I don’t know, I’m sure.’ The five pounds hung alluringly before Mrs Fowler’s eyes. ‘I knew Mrs Ascher, of course, but as to writing anything.’

Hastily Poirot reassured her. No labour on her part was required. He would elicit the facts from her and the interview would be written up.

Thus encouraged, Mrs Fowler plunged willingly into reminiscence, conjecture and hearsay.

Kept herself to herself, Mrs Ascher had. Not what you’d call really friendly, but there, she’d had a lot of trouble, poor soul, everyone knew that. And by rights Franz Ascher ought to have been locked up years ago. Not that Mrs Ascher had been afraid of him—real tartar she could be when roused! Give as good as she got any day. But there it was—the pitcher could go to the well once too often. Again and again, she, Mrs Fowler, had said to her: ‘One of these days that man will do for you. Mark my words.’ And he had done, hadn’t he? And there had she, Mrs Fowler, been right next door and never heard a sound.

In a pause Poirot managed to insert a question.

Had Mrs Ascher ever received any peculiar letters—letters without a proper signature—just something like ABC?

Regretfully, Mrs Fowler returned a negative answer.

‘I know the kind of thing you mean—anonymous letters they call them—mostly full of words you’d blush to say out loud. Well, I don’t know, I’m sure, if Franz Ascher ever took to writing those. Mrs Ascher never let on to me if he did. What’s that? A railway guide, an A B C? No, I never saw such a thing about—and I’m sure if Mrs Ascher had been sent one I’d have heard about it. I declare you could have knocked me down with a feather when I heard about this whole business. It was my girl Edie what came to me. “Mum,” she says, “there’s ever so many policemen next door.” Gave me quite a turn, it did. “Well,” I said, when I heard about it, “it does show that she ought never to have been alone in the house—that niece of hers ought to have been with her. A man in drink can be like a ravening wolf,” I said, “and in my opinion a wild beast is neither more nor less than what that old devil of a husband of hers is. I’ve warned her,” I said, “many times and now my words have come true. He’ll do for you,” I said. And he has done for her! You can’t rightly estimate what a man will do when he’s in drink and this murder’s a proof of it.’

She wound up with a deep gasp.

‘Nobody saw this man Ascher go into the shop, I believe?’ said Poirot.

Mrs Fowler sniffed scornfully.

‘Naturally he wasn’t going to show himself,’ she said.

How Mr Ascher had got there without showing himself she did not deign to explain.

She agreed that there was no back way into the house and that Ascher was quite well known by sight in the district.

‘But he didn’t want to swing for it and he kept himself well hid.’

Poirot kept the conversational ball rolling some little time longer, but when it seemed certain that Mrs Fowler had told all that she knew not once but many times over, he terminated the interview, first paying out the promised sum.

‘Rather a dear five pounds’ worth, Poirot,’ I ventured to remark when we were once more in the street.

‘So far, yes.’

‘You think she knows more than she has told?’

‘My friend, we are in the peculiar position of not knowing what questions to ask. We are like little children playing cache-cache in the dark. We stretch out our hands and grope about. Mrs Fowler has told us all that she thinks she knows—and has thrown in several conjectures for good measure! In the future, however, her evidence may be useful. It is for the future that I have invested that sum of five pounds.’

I did not quite understand the point, but at this moment we ran into Inspector Glen.