По всем вопросам обращайтесь на: info@litportal.ru

(©) 2003-2025.

✖

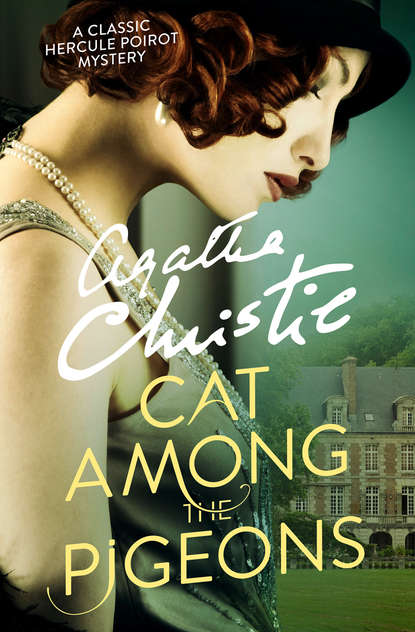

Cat Among the Pigeons

Автор

Год написания книги

2019

Настройки чтения

Размер шрифта

Высота строк

Поля

‘How idiotic,’ said Mrs Sutcliffe. ‘I’m sure Bob would never use anything like invisible ink. Why should he? He was a dear matter-of-fact sensible person.’ A tear dripped down her cheek again. ‘Oh dear, where is my bag? I must have a handkerchief. Perhaps I left it in the other room.’

‘I’ll get it for you,’ said O’Connor.

He went through the communicating door and stopped as a young man in overalls who was bending over a suitcase straightened up to face him, looking rather startled.

‘Electrician,’ said the young man hurriedly. ‘Something wrong with the lights here.’

O’Connor flicked a switch.

‘They seem all right to me,’ he said pleasantly.

‘Must have given me the wrong room number,’ said the electrician.

He gathered up his tool bag and slipped out quickly through the door to the corridor.

O’Connor frowned, picked up Mrs Sutcliffe’s bag from the dressing-table and took it back to her.

‘Excuse me,’ he said, and picked up the telephone receiver. ‘Room 310 here. Have you just sent up an electrician to see to the light in this suite? Yes…Yes, I’ll hang on.’

He waited.

‘No? No, I thought you hadn’t. No, there’s nothing wrong.’

He replaced the receiver and turned to Mrs Sutcliffe.

‘There’s nothing wrong with any of the lights here,’ he said. ‘And the office didn’t send up an electrician.’

‘Then what was that man doing? Was he a thief?’

‘He may have been.’

Mrs Sutcliffe looked hurriedly in her bag. ‘He hasn’t taken anything out of my bag. The money is all right.’

‘Are you sure, Mrs Sutcliffe, absolutely sure that your brother didn’t give you anything to take home, to pack among your belongings?’

‘I’m absolutely sure,’ said Mrs Sutcliffe.

‘Or your daughter—you have a daughter, haven’t you?’

‘Yes. She’s downstairs having tea.’

‘Could your brother have given anything to her?’

‘No, I’m sure he couldn’t.’

‘There’s another possibility,’ said O’Connor. ‘He might have hidden something in your baggage among your belongings that day when he was waiting for you in your room.’

‘But why should Bob do such a thing? It sounds absolutely absurd.’

‘It’s not quite so absurd as it sounds. It seems possible that Prince Ali Yusuf gave your brother something to keep for him and that your brother thought it would be safer among your possessions than if he kept it himself.’

‘Sounds very unlikely to me,’ said Mrs Sutcliffe.

‘I wonder now, would you mind if we searched?’

‘Searched through my luggage, do you mean? Unpack?’ Mrs Sutcliffe’s voice rose with a wail on that word.

‘I know,’ said O’Connor. ‘It’s a terrible thing to ask you. But it might be very important. I could help you, you know,’ he said persuasively. ‘I often used to pack for my mother. She said I was quite a good packer.’

He exerted all the charm which was one of his assets to Colonel Pikeaway.

‘Oh well,’ said Mrs Sutcliffe, yielding, ‘I suppose—If you say so—if, I mean, it’s really important—’

‘It might be very important,’ said Derek O’Connor.

‘Well, now,’ he smiled at her. ‘Suppose we begin.’

II

Three quarters of an hour later Jennifer returned from her tea. She looked round the room and gave a gasp of surprise.

‘Mummy, what have you been doing?’

‘We’ve been unpacking,’ said Mrs Sutcliffe crossly. ‘Now we’re packing things up again. This is Mr O’Connor. My daughter Jennifer.’

‘But why are you packing and unpacking?’

‘Don’t ask me why,’ snapped her mother. ‘There seems to be some idea that your Uncle Bob put something in my luggage to bring home. He didn’t give you anything, I suppose, Jennifer?’

‘Uncle Bob give me anything to bring back? No. Have you been unpacking my things too?’

‘We’ve unpacked everything,’ said Derek O’Connor cheerfully, ‘and we haven’t found a thing and now we’re packing them up again. I think you ought to have a drink of tea or something, Mrs Sutcliffe. Can I order you something? A brandy and soda perhaps?’ He went to the telephone.

‘I wouldn’t mind a good cup of tea,’ said Mrs Sutcliffe.

‘I had a smashing tea,’ said Jennifer. ‘Bread and butter and sandwiches and cake and then the waiter brought me more sandwiches because I asked him if he’d mind and he said he didn’t. It was lovely.’

O’Connor ordered the tea, then he finished packing up Mrs Sutcliffe’s belongings again with a neatness and a dexterity which forced her unwilling admiration.

‘Your mother seems to have trained you to pack very well,’ she said.

‘Oh, I’ve all sorts of handy accomplishments,’ said O’Connor smiling.

His mother was long since dead, and his skill in packing and unpacking had been acquired solely in the service of Colonel Pikeaway.

‘There’s just one thing more, Mrs Sutcliffe. I’d like you to be very careful of yourself.’

‘Careful of myself? In what way?’